For all that, it was in the next race, at St Jovite, that Cevert gave notice of serious intent. By now Tyrrell had launched its first car, in which Stewart took pole position and dominated while it lasted, but Cevert, still in the unloved March, qualified fourth, and fought with Amon’s similar car until a damper broke. Given that Chris was always exceptional at this true driver’s circuit, François’s performance registered.

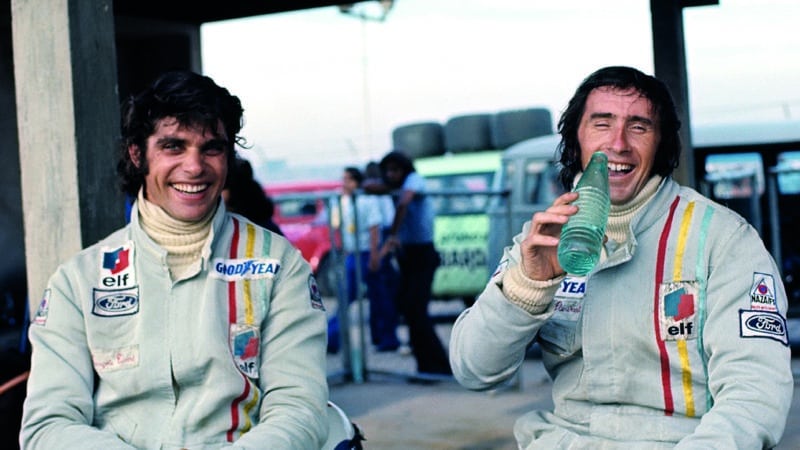

In terms of results, the high point of the season was a victory for Matra, co-driving with Jack Brabham in the Paris 1000Kms at Montlhéry, but Cevert’s F1 prospects were excellent, for in 1971 he would be driving a Tyrrell, and continuing to benefit from the experience of the genius in the other car. By now the relationship with Stewart was beyond that of amicable team-mates: the two men were firm friends, and there was an echo of Fangio and Moss in the way Jackie held nothing back in his advice to François.

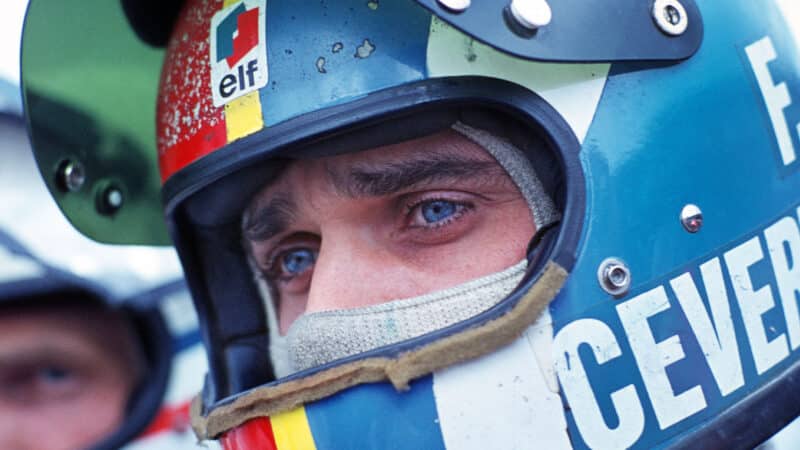

If the results had yet to come, Cevert had swiftly established himself in the F1 fraternity, not least because of his natural glamour. As with Paul Newman, everyone noticed his startlingly blue eyes, but if he were good-looking in a way that had girls gnawing at the back of their hands he carried it off with such grace that none could dislike him for it: not always the case, as others have shown.

“The thing about François,” said Stewart, “was that he was absolutely unpretentious and genuine – not at all infatuated with himself, as so many people like him are. He was from a very rich Jewish family, but from the way he was you’d never have known about the wealth.

“It’s fair to say that his relationships tended to be… on-off sorts of things – he was young, spectacularly good-looking and never short of company. I remember one day getting back from the track in Sweden – where we’d stay in people’s houses because there were no hotels near the circuit – and there was François in the shower with two of the Marlboro girls! I’m not sure he was… ready to marry, let’s put it that way, whereas Christina, his regular girlfriend towards the end, was, I think.”

Frenchman was popular both at and away from the track

Whatever else, Cevert was never less than intensely serious about his job. From the beginning he revered Stewart, appreciating that he was working with the best: any time Jackie had words of counsel for him, be it specifics about the car or simply managing a grand prix weekend, he was going to listen.

In 1971 Stewart took the second of his three world championships, and Cevert, maturity growing by the race, finished third in the points standings, with second places (to JYS) at Zandvoort and the Nürburgring, a third at Monza – and finally, at Watkins Glen, a victory, the first by a French driver since 1958.

After 15 laps the Tyrrells were running 1-2, but then Stewart’s car began to understeer badly and Cevert was waved by. Later he came under pressure from Jacky Ickx, but that evaporated when the Ferrari retired with an alternator problem. At the finish the Tyrrell was 40 seconds clear of Jo Siffert’s BRM and Ronnie Peterson’s March.

In all my years of following F1, I doubt I’ve ever seen a more joyful winner than Cevert that unclouded autumn afternoon in upstate New York. Back then there was no formal podium, but there stood François, with the widest smile in the world, clutching his trophy as Chris Economaki interviewed him. Well-wishers engulfed him and I couldn’t get near, so I pointed my camera between the heads, pressed the shutter and hoped for the best.

Cevert celebrates his only F1 win at Watkins Glen ’71

DPPI

So often in those days, though, a sting swiftly followed celebration. Three weeks after the US GP, a non-championship F1 race – the fifth in England that year – was organised at Brands Hatch following the late cancellation of the Mexican Grand Prix. It was named ‘The Victory Race’, in honour of Stewart’s title, but on a sorrowful day Jo Siffert died at the circuit where he had scored his most memorable victory: there would be a similar resonance in the racing world two years later.

No grand prix wins came Cevert’s way in 1972, his best places a pair of seconds at Nivelles and Watkins Glen, but drivers did not then confine themselves to F1, and François raced a variety of other cars, finishing second at Le Mans (sharing a Matra with Howden Ganley), second at Thruxton (in an F2 March), second at Paul Ricard (in a Cologne Capri shared with Stewart) – and first at Donnybrooke, one of five Can-Am races in which he drove a McLaren. It was a full life he led.

Early in 1973 Cevert triumphed at the F2 race at Pau, and crewed the victorious Matra at the Vallelunga Six Hours, but although he would six times finish second in Grands Prix (three of them on the heels of Stewart), there would be no more wins.

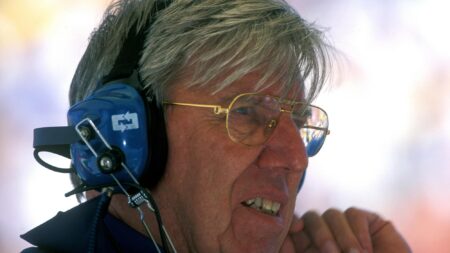

The last of those Tyrrell one-twos came at the Nürburgring, and years later Tyrrell would suggest that afterwards Stewart told him that, ‘François could have passed me any time he liked…’