The advantage that I and my fellow scribes had in those days was the ability to influence race team owners into testing future F1 talent. We were effectively the talent scouts who travelled Europe week in, week out covering all the races. Max Mosley and Robin Herd at March were particularly receptive to our views, and I think Gunnar did himself a power of good when he contested the final two end-of-season F3 events in Britain.

At Brands Hatch in mid-October I was there when he plonked his March on pole, but a misfire ended his chances. Two weeks later at Thruxton he led impressively, but then spun away what would have been his first ever win. He was fast, but impetuous. But he had certainly been noticed. By the start of the following season, he’d ‘wheeled and dealed’ his way into the March F3 team by trading in his existing race car (worth about 20 per cent of a proper F3 budget) and little else to cement a plum drive alongside Brazilian Alex Dias Ribeiro, whose own sponsorship basically funded both cars!

I remember thinking that if Gunnar could broker such a deal, then our boy from Helsingborg wasn’t as wet behind the ears as many others we’d encountered.

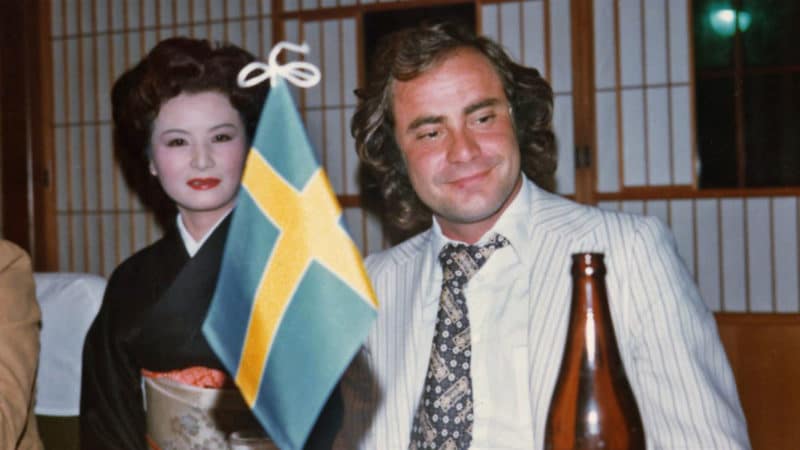

Powersliding along at his home grand prix in Anderstorp, Sweden

Grand Prix Photo

Gunnar’s arrival into one of the best F3 seats coincided with BP Oils’ decision to sponsor the national series, which now became a massive 20-round championship with qualifying rounds at many major races including the Monaco, Swedish and British Grands Prix. Gunnar won the opening round (his first race win) at Thruxton and went on to take the title, scoring seven more victories that season plus a succession of poles and fastest laps.

His speed attracted the interest of Ted and Kenny Moore, the father and son who owned Formula Atlantic team Rapid Movements, and with a brand new Chevron B29 at their disposal – the chassis to have at the time – plus the approval of myself and Ian Phillips, then editor of Autosport and now serving a ‘life sentence’ within F1, the Moores gave Gunnar the drive. Five straight wins from five starts to complement his inaugural F3 title was enough to get him his first F1 test with Frank Williams. He was again impressive and Frank made him an offer, but Gunnar, who always managed his own affairs, wanted to keep his options open.

It was during this time that we all started to socialise more away from the race tracks and Gunnar became good friends with many of us, including his F3 rivals Danny Sullivan and Rupert Keegan. The fact that we all lived in west London at either end of Ladbroke Grove helped. I travelled to Helsingborg on the western seaboard of Sweden to visit his modest home, and spent time with him and his Danish mother Elisabeth at the family house on the Danish island of Bornholm in the Baltic Sea. Gunnar was an only child although he had a half brother, Stig, from his father’s previous marriage. His Swedish father, who had created and built up a large construction and property portfolio in the town, had died when he was 15. He and his mother were therefore very close. She was always feeding me smørrebrød and herring roll mops whether I liked them or not!