The cruellest loss was at Indy. The Andretti family’s ill luck at the Brickyard is legendary, of course, and even though he won it himself that year Unser Jnr has a little sympathy for Michael: “Everyone remembers that race as me beating Scott Goodyear by a fraction of a second and that we did it in the Galmer. But the reality is that battle should have been for second place. I mean, Michael was gone! He was in a class all of his own that year. Then with about 10 laps to go he breaks and gives me my chance.”

Two years later Unser, having switched to Penske just as it became dominant, would win Indy again and follow this up with his second CART title. In the meantime, Michael to this day feels he sacrificed a tilt at both those accolades by making his ill-fated move to Formula 1, handing the keys to the best IndyCar to Nigel Mansell, who was crossing the Atlantic in the opposite direction.

“Yeah, big mistake because by 1993 that Cosworth had the reliability to go with its power. Before I signed the deal with McLaren it was constantly in my mind about what I was sacrificing. I think one of those sacrifices was the Indy 500. Nigel gave that race away on the final restart because of his inexperience, and I don’t think I’d have made that same mistake.”

When Andretti’s unhappy sojourn at McLaren ended and he returned to IndyCars in 1994, driving the Chip Ganassi-run Reynard, it was with some relish that he beat Mansell — and indeed everyone else — in his first race back. But neither he nor Nigel had any answer to the Penskes throughout the rest of the year, and when Mansell went back to Europe at year’s end Andretti was able to return to his spiritual home at Newman/Haas for ’95. On reflection that might not have been the wisest move: from ’96 to ’99 only Ganassi drivers won the CART title, driving Reynard-Hondas on Firestone tyres. Armed with a Lola-Ford on Goodyears, Andretti challenged ’96 champ Jimmy Vasser hard, but Newman/Haas switched to Swift in ’97 and, although Michael was fully supportive of Carl Haas’s decision to try to beat Ganassi by doing something different, wins were pretty thin on the ground.

Not as thin as they were for old rival Unser Jnr, who by the late ’90s only got to see Michael on track as the Newman/Haas car went past to lap him. After stoutly defending his Indycar title in ’95 (albeit in vain), the fortunes of Unser and Penske went into sharp decline. Failing to qualify at Indy in ’95 had been a low point, but at least there had been four wins. As things transpired, his victory in Vancouver that year would prove to be his last CART success. He couldn’t figure out the Penske PC25 on road courses, and in ’97 it was team-mate Paul Tracy who grabbed three oval wins on the trot. By ’98 the team’s engine partner Mercedes had also slipped well away from the cutting edge of technology.

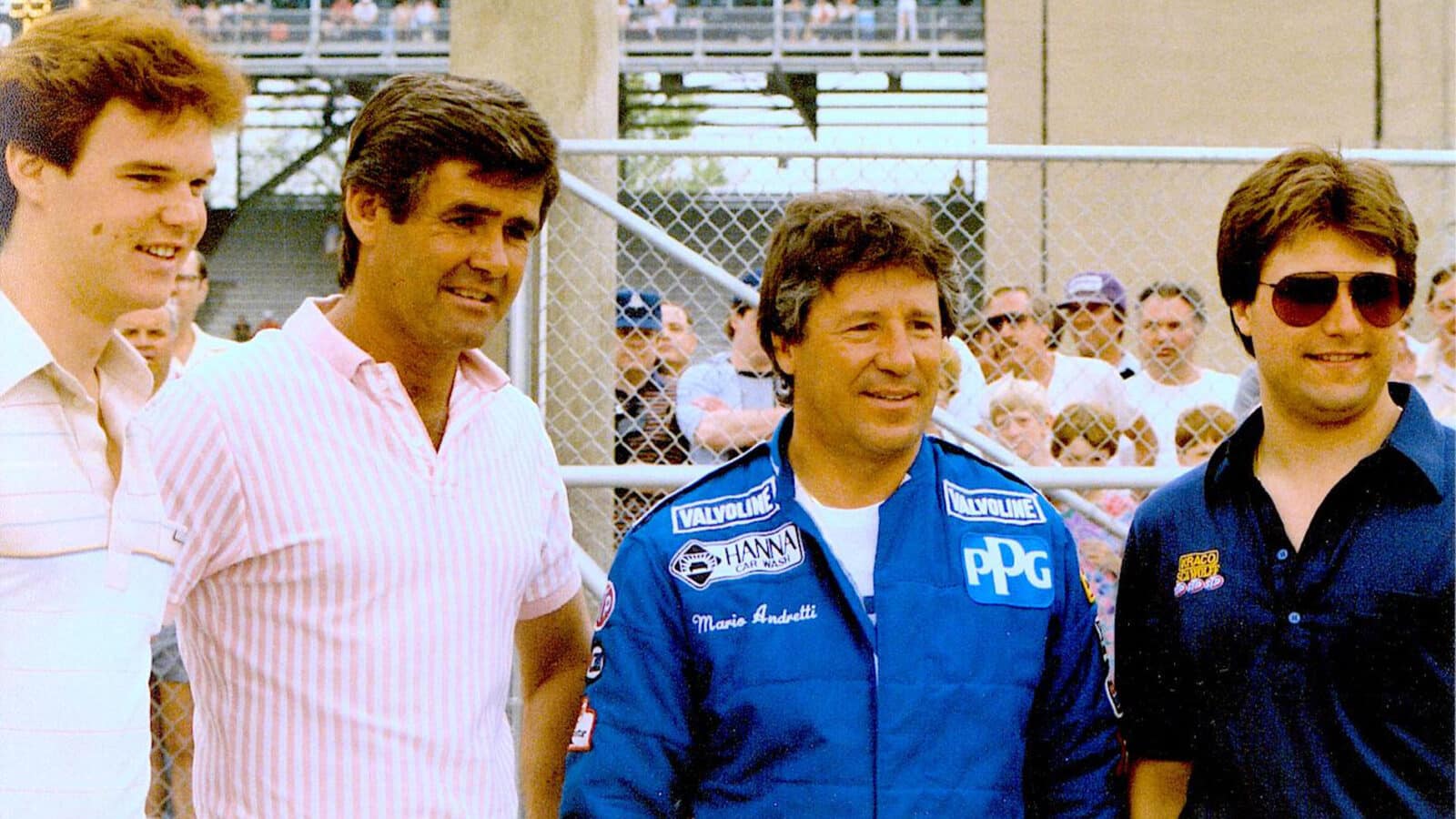

Andretti and Unser say their on-track battles never spilled into animosity

Getty Images

If the car wasn’t up to much, neither was Al. His 18-year marriage to Shelley was ending, he was drinking heavily, had let himself get dreadfully unfit and, in early 1999, his family suffered a huge blow when eldest daughter Cody was struck by transverse myelitis, leaving her paralysed from the chest down. It was hardly surprising then that his racing was half-hearted, and unsurprising too that Roger Penske could no longer justify the retention of his services.

Some semblance of order had returned to his life by 2000, when he switched to the (then) all-oval Indy Racing League and, over the next four seasons, he added three IRL victories to his CART tally of 31. He also went through rehab after again falling prey to bouts of excess alcohol, culminating in a much-publicised roadside brawl with his girlfriend. Then he quit the sport, citing loss of enthusiasm and alarm at the driving standards in the IRL series as his (de)motivational factors.

By then Andretti had joined him in the IRL, albeit as a team owner. Michael had departed Newman/Haas at the end of 2000, after 10 seasons, to join Team Green in a three-car operation (along with Dario Franchitti and Paul Tracy) and the trio competed in the IRL-sanctioned Indy 500 in 2001 and ’02. After buying into the team in ’02, and scoring his 42nd and final CART victory, he and Barry Green switched across to the IRL full-time to form Andretti Green Racing, with full Honda backing. Andretti started the 2003 IRL season in order that he could compete at Indy for the 14th and final time, and had led 28 of the opening 94 laps when (predictably) his car failed with a broken throttle linkage. He then retired from the cockpit for good.

Al Sr gets some advice from Jr

Getty Images

Since then Andretti Green Racing has become the IRL team to beat, and in both 2004 and ’05 has produced the series champions — Brazil’s Tony Kanaan and Briton Dan Wheldon this time around. Gratifyingly, this year Wheldon also put the Andretti name in the Indy 500 victory circle for the first time since Mario won the race in 1969.

It strikes one as strange, then, that two careers that so closely paralleled each other should have now so comprehensively gone their separate ways. Andretti has made a real success out of his racing team, while Unser has slipped into obscurity. Now their sons, Marco Andretti and Al Unser III, are trying to make their way to the uppermost branches of single-seater racing and the former, at least, is showing every sign of becoming an ace.