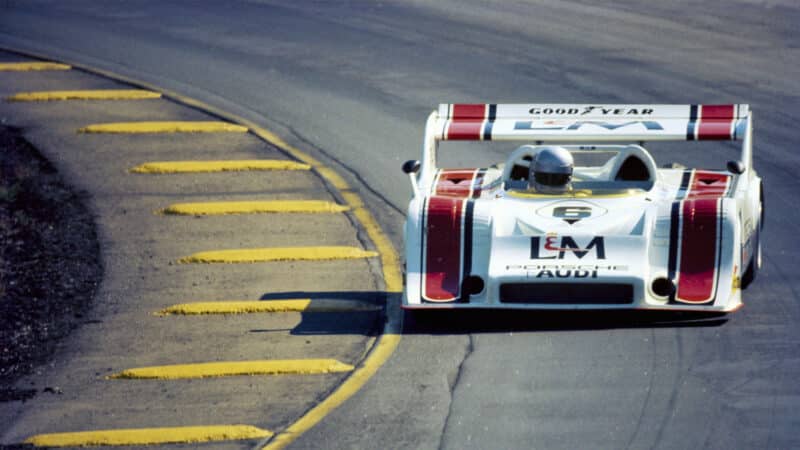

Why him? Well, he was as versatile as they came. He’d already driven for Penske in the Can-Am and Trans-Am series in years past. He’d won races in Formula 5000 and IndyCars. In years to come, he’d run a Shadow in Formula 1, scoring points in his first two grands prix, and even a hulking stock car for NASCAR legend Bud Moore. “Donohue was a better engineer,” recalls Klaus Bischof, a factory mechanic on the 917/10. “But Follmer had a bigger heart.”

What Follmer needed at Road Atlanta, however, was cojones. Because the wheelbase was so short, the Porsche was twitchy in fast corners. There was substantial turbo lag, forcing the driver to commit to the throttle long before reaching the apex of the corner. But when the turbo spooled up, the engine produced nearly 900 horses.

“Even now, it’s an awesome car. By the standards of the day, it was…” Follmer falls silent, unable to come up with an appropriately impressive description. “Let’s just say that I was under a lot of pressure that weekend. The car was fast, and everybody knew it was fast. I knew I had to perform.”

Follmer also knew that he couldn’t screw up. Although he’d driven turbocharged IndyCars, he’d never been in anything like the Porsche. Driving conservatively around a tricky track, he qualified second. But he rocketed past Hulme, the pole-sitter, before reaching Turn 1, and he led to the chequered flag. History had been made, and road racing would never be the same again.

Donohue dominated in 917/10, before disaster struck

Getty Images

Ironically, considering the impact it would have on the sport, the 917/10 was an afterthought at Porsche. The impetus for its creation was the imposition of a 3-litre limit for the World Championship of Makes for 1972. As a result, Porsche’s magnificent 5-litre 917, the car that won Le Mans in 1970 and ’71, was rendered instantly obsolete.

“Porsche was a very small company in those days, and we had spent a lot of money on the 917,” says Helmut Flegl, project manager for the car. “So the question was: What could we do with the car? And the Can-Am had a very short rule book.”

“Mark was a driver who spoke the engineer’s language”

The Canadian-American Challenge Cup was the world’s most lucrative bastion of no-holds-barred racing. Enclosed wheels, open bodywork, two seats — other than that, pretty much anything went. Also, Porsche already had some experience in the series: Jo Siffert had run a 917 spyder with modest success in 1969 and ’71. But despite the power of the normally aspirated flat-12 engine, the Porsche didn’t have enough grunt to hang with big-block Chevys hogged out to 8000cc.

For 1972, Porsche embarked on two parallel programs: developing a 16-cylinder engine and slapping a pair of turbochargers on the existing flat-12. Early development showed the turbo offered more potential. At Ferdinand Piech’s command, the blown 12 got the nod, and the flat-16 was shelved.

The Can-Am car was a 917 with an open body designed not to minimise drag — the goal at Le Mans — but to maximise downforce for the tighter North American tracks. The spaceframe chassis was modified to accept the larger engine. Also, Porsche developed a stout four-speed transmission to accommodate the additional power of the turbo. Bigger brakes were fitted because the low-compression motor didn’t produce much engine braking.