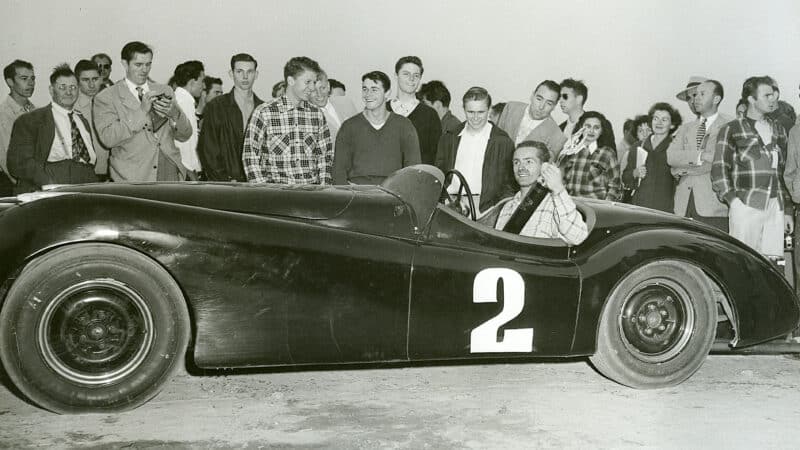

“We were just a small team of enthusiasts, but we had cast some special alloy wheels for the Jaguar that incorporated the brake drum into the wheel, just as Bugatti used to do. The trouble was that the wheels got so incredibly hot from the overworked drums that the tyres caught fire. So that was no good and we had to use the standard steel wheels and separate brake drums. The brakes were so bad that they’d fade completely the first time they were used hard. I had to go down an escape road in the preliminary race.”

Yet Hill won despite starting from the back of the grid; the Jaguar’s clutch had burnt out and he had to be push-started.

From the start-finish straight, we drive through the trees on Portola Road to the first corner, a tight right that leads onto Sombaria Lane.

“The roads were pretty narrow and not very well defined,” explains Hill. “Once you were off the asphalt you were onto dirt and then into the trees. It was a pretty dangerous place, with the crowds just held back with snow fencing.”

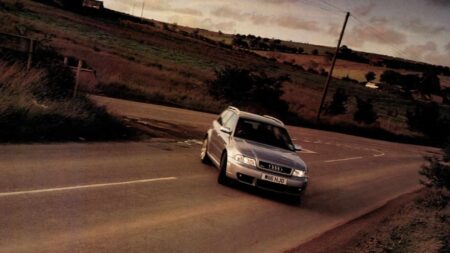

Carefully groomed hedges on today’s Drake Road replace straw bales of 1950

Andrew Yeadon

For the first year a 1.8-mile circuit was used, which was then lengthened to 2.1 miles. From Sondria Lane, you have a short straight to another right-handed corner, again with an escape road dead ahead, after which you take Drake Road. There was no safety net on this part of the circuit; come off along here and you had to hope that the car would spin to a stop before the trees. The last part of it is uphill with crests and kinks; to have driven a sportscar with a power-to-brakes ratio well on the side of terrifying must have required a great deal of confidence.

Cars such as the 6-litre Cadillac-powered Allard owned by Tom Carstens and driven by Bill Pollack in the 1951 event, that year held in April over the longer course.

Pollack and the Allard became a famous pairing in West Coast sports car racing.

According to Hill, “Pollack was the guy to beat”. No doubt lessons learnt the year before put Hill off driving Jag XKs, so for ’51 he drove his recently purchased Alfa 8C. He won the preliminary race in it, so lined up for the 48-lap main event as favourite. But after 20 lead-swapping laps between Pollack, Hill and another Allard-Cadillac driven by Jack Armstrong, Pollack’s white-walled Allard finally took the win.

“Pebble Beach was a beautiful place to hold a race,” remembers Pollack. “There was almost a fantasy quality to the place. The view out to the Pacific Ocean. Sea mists. Fabulous. The atmosphere was very special, too. Although the country’s top sports car drivers would be at Pebble Beach, and a few like myself were driving cars for their owners, it was still very much an amateur event with people turning up and racing their own cars.”

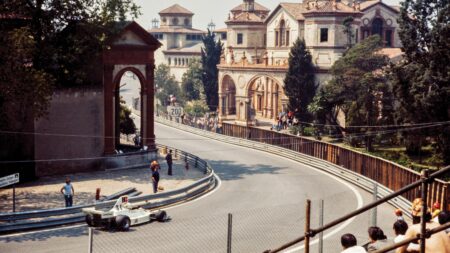

Vintage race in 1955

Getty Images

Two of the best-known entrants were Edgar and Parravano. Both were larger-than-life characters, who perfectly fitted the classy and stylish atmosphere at Pebble Beach. Edgar was definitely the kind of enthusiast of which legend is made. He entered cars for drivers such as Pollack and Jack McAfee; a long list of injuries sustained in hydroplane racing before the war — a set of broken ribs and an absent kidney — had left him in no shape to race cars competitively himself. He had not lost his love of speed however, as he could be seen riding his Vincent Black Lightning around Beverley Hills, until one day he dropped it and broke an arm and shoulder.

Parravano was an even more intriguing personality. This Italian entrepreneur made a fortune in the construction business in California and got the racing bug when McAfee, a talented driver, invited him to the races. Parravano would eventually own a superb scuderia of Ferraris and Maseratis, driven by McAfee, Carroll Shelby, Gregory and Miles. Then, one morning in April 1960, Parravano disappeared. He was never seen again, and mystery still surrounds his disappearance.

The Pebble Beach races of 1952 saw some interesting new machinery. Hill came to the Monterey peninsula with a Ferrari 212 he had bought from Luigi Chinetti. However, he’d already committed to drive a lightweight XK120, so let a friend called Arnold Stubbs drive the 212.