Oddly enough, it was an attempt by the authorities to stop Ferrari walking away with the championship that gave the 500 the chance it needed. By the end of 1951, the end was nigh for the Alfa-Romeo 159. A prewar design, it had mopped up in 1950 to make Dr Giuseppe Farina the inaugural World Champion, but by the time Froilan Gonzalez’s Ferrari 375 slid wildly to victory at Silverstone the following season the writing was on the wall for Alfa. The 159 could be developed no further, while the 375 was just getting warmed up, as its victory in three of the last four GPs of the season showed. Worse, the great white hope of England, the V16 BRM, was fast turning into a great white whale with little chance even of finishing a Grand Prix, let alone winning. There was no works Maserati team and the private 4CLTs that did venture out were utterly overwhelmed by their rivals on the other side of Modena. Unless something was done, Ferrari was going to march unopposed through the ’52 season.

The following two seasons were thus run to Formula Two regulations, with a normally aspirated limit of 2-litres. Ferrari got its walkover all the same — it was simply the 500 rather than the 375 that took the credit. For 1953, though, Fangio was back and this time he was on board a works Maserati. Still the 500 was untouchable, until that last race at Monza, Ascari’s spin and Fangio’s lucky, inherited win.

In typical Ferrari fashion, you’ll spend all day crawling over the 500 trying to find any particular trick to explain such absurd dominance. And you will fail. The engine, while a masterpiece, is entirely conventional. Yes, it has twin ignition with eight spark plugs, but that was scarcely rocket science even before the war. Four beautiful sidedraught Webers are bolted to one side of the light alloy engine which uses just two valves per cylinder to generate an honest 240bhp at 7200rpm in this 2.5-litre form, and around 180bhp in 2-litre F2 specification.

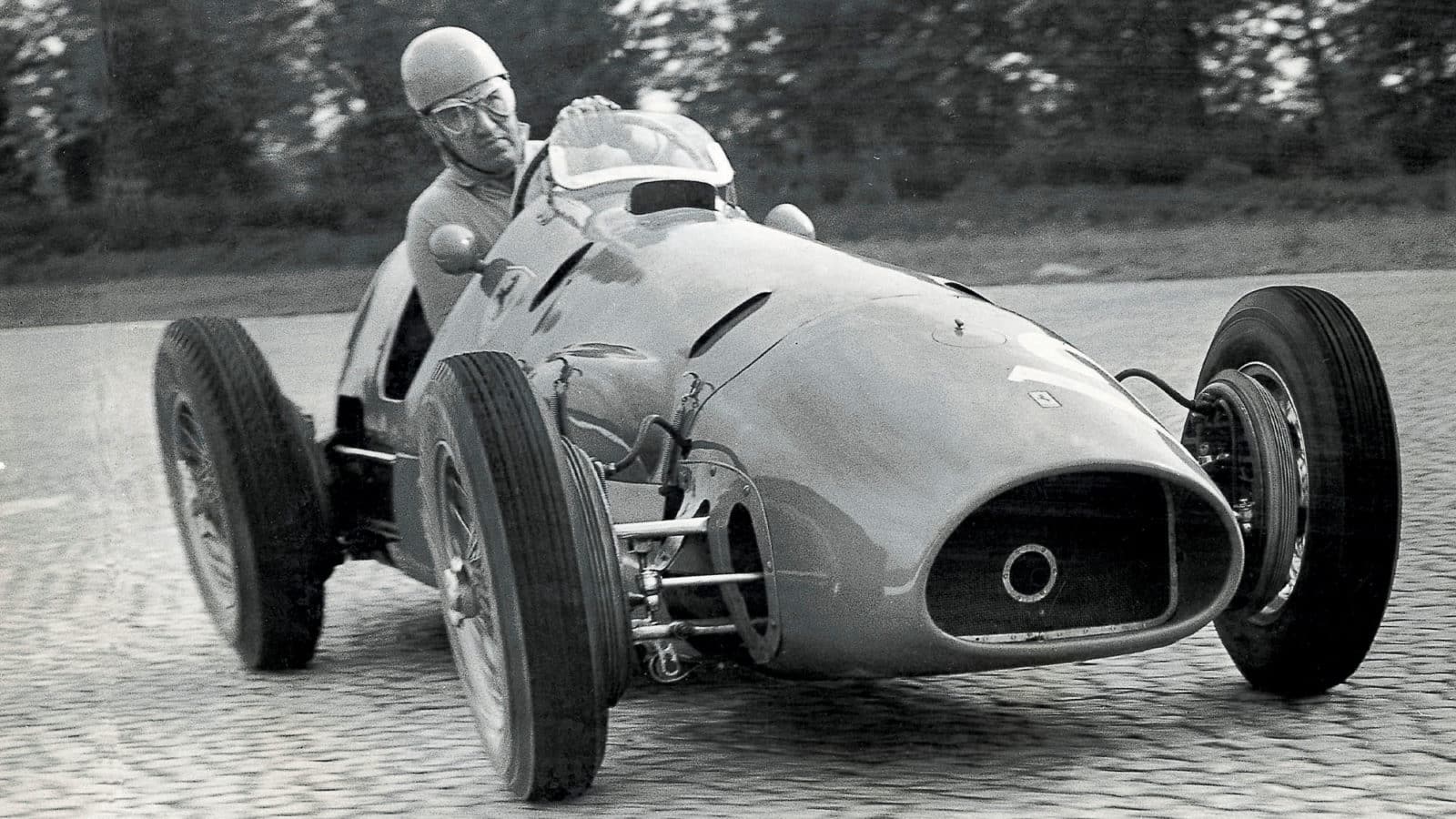

Claiming victory at Spa in 1952

DPPI

The engine, then, is utterly straightforward and, if it has a secret, this is it. Lampredi’s motor was not only more compact and lighter than the V12 212 model that the 500 replaced, it was also stiffer, less complex, more reliable, less prone to frictional losses and, ultimately, a deal more powerful, not to mention the massive torque advantage four big pistons will always wield over twelve tiny ones.

And throughout the rest of the car, convention rules. The chassis comprises two parallel steel rails with transverse cross-members on which sits its elegant aluminium monoposto bodywork. Suspension followed traditional Ferrari thinking of the day, with double unequal length wishbones at the front linked by a transverse leaf spring and a similarly sprung De Dion rear axle located by radius arms.

Now it is warm. At idle, to be honest, it sounds like anything other than a Ferrari. Enzo won World Championships with four, six, eight and twelve cylinders, but if your mind’s ear has an idea of how a Grand Prix Ferrari should sound, you have my word it is nothing like this. It’s loud, of course, but more crisp than mellow. At idle, there’s none of the fascinating whirrings of a multi-cylinder Columbo unit, just a straightforward, baritone burble.

The cockpit sides are low, the aperture generous. There is, of course, nothing you’d mistake for roll-over protection: the drivers of the day considered their chances of survival in an accident were higher out of the car than in, which may explain why cockpit seems purposely designed facilitate rapid evacuation.