Ronnie was 42 when he started to race Formula Vee in 1966. Despite his late start, he was no slouch — he beat Brian Henton to win the final round of the British championship in 1970. Two years later he made the move up to the more powerful SuperVee cars. When he heard that Lola had an available chassis, he did a deal with factory manager Derek Ongam.

“He had a Formula Ford which was being converted to a SuperVee,” recalls Ronnie, “but he didn’t have an engine. I phoned him up said ‘I’ve got an engine, you’ve got a car; can we get together?’ He said ‘Bring the engine up and we’ll have a look’.”

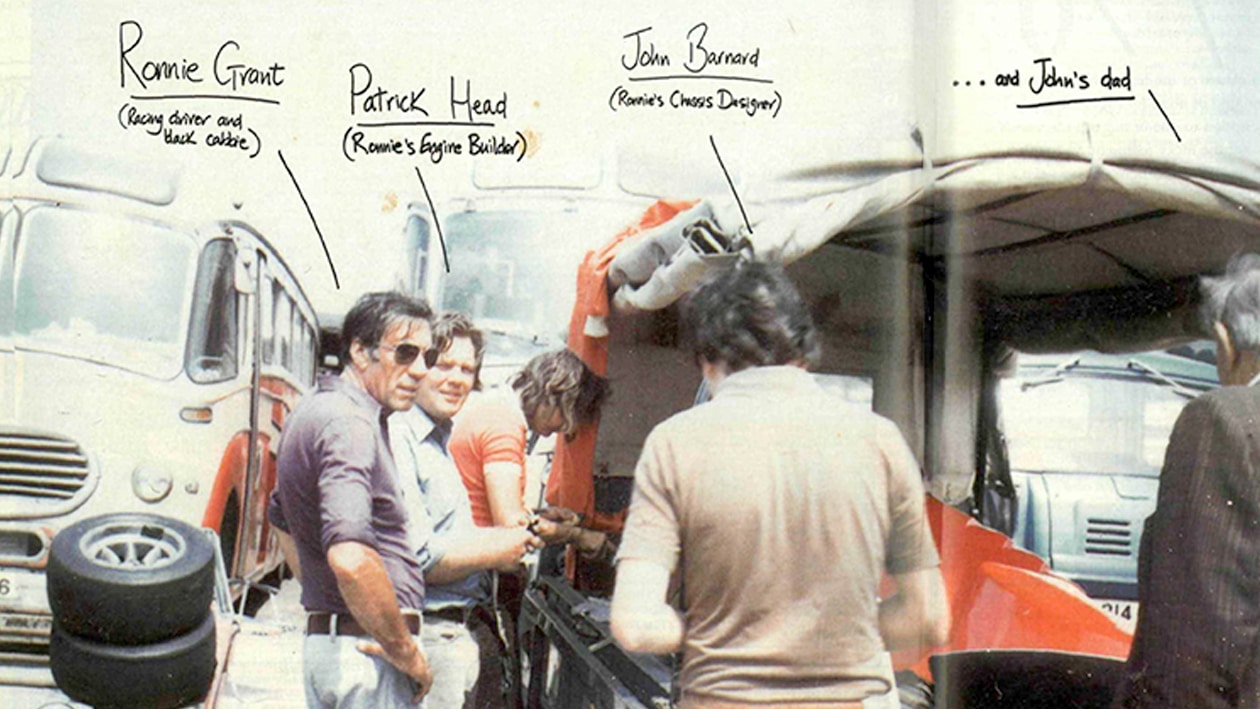

In those days Lola was a hive of activity, and among the staff working under Eric Broadley’s guiding hand were budding designers Patrick Head and John Barnard, who were stationed on adjacent drawing boards. Despite their proximity, they only rarely worked on the same project.

“The idea that somebody could be a quick driver when he was 48 was a bit of a joke to us”

“We worked quite closely together on the T290 sportscar,” says Head today, “and the T280, which was the 3-litre version — unfortunately it was the car in which Jo Bonnier got killed. Generally John was quite good at having his own projects, and not working with other people on them! I joined a year or so after John, and was drawn into whatever project was going on. It was never decided whether he was my boss or I was his boss…

“We were told that a chap called Ronnie Grant was sending an engine up to be installed in a car, and they were going to go out and do some testing. Somebody said that this guy was quite good, but that he was 48 years old or something.

“I remember John and I almost falling about. It shows how dreadful the youth can be – I suppose we were in our late 20s at the time. The idea that somebody could be a quick driver when he was 48 was a bit of a joke to us. And he was a taxi driver as well. I think John went to the first test at Snetterton, and took to Ronnie straight away. He thought he was a real character, an amusing fellow. I think he was quite impressed with him as a driver as well.”

“It was John’s job to get it all up and running,” explains Ronnie, “so he’d come testing with me. I wasn’t a very good test driver at the time, just coming off Vees, I didn’t really study all that hard. Gerry Birrell used to garage with me he also used to live with me on and off and he set the old Vee up, and I used to just get in and go.”

Ronnie gets to grips with the Taurus in the wet during 1974

Barnard was happy to use some of his own time on the project, even after he left Lola to join McLaren for his first unheralded stint in 1972. Patrick also left Lola at around the same time, with a vague plan to go into business preparing SuperVee engines in Huntingdon, but, “about a week after I started the place burned to the ground.

“So, I was working in a railway arch in Battersea, which was only about a mile from where Ronnie was in Clapham. I started working part time for him at Trojan. At that time I also started building a boat. I was a little bit itinerant…”

“There were lots of characters around the place, taxi drivers called Coldhands and Lefty”

Through Grant, Head then had a second crack at the engine business. Suddenly Ronnie had both John and Patrick helping in his pit at races.

“I based myself partly at Ronnie’s place,” says Head, “and I was doing SuperVee engines though not really in any commercial sense. I’m not sure if ever asked Ronnie if it was OK I just plonked myself at his facility. He was very good at keeping me out of trouble. There were lots of characters around the place, taxi drivers called Coldhands and Lefty.”

“The only reason he stayed with me was that I had an engine brake where we could try the engines out,” says Grant. “We’d be in there at 11 o’clock at night revving these things like there’s no tomorrow, and we used to get the neighbours from the next road phoning up and complaining about the noise!”