1981 Canadian Grand Prix race report

Jacques Laffite took a second win of the season for Ligier in challenging conditions

Motorsport Images

Heroes all

Montreal, September 27th

I am sure most people arrived in Canada expecting the mm-st as far as thc weather was concerned, and they were not disappointed on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday or Thursday, whichever day on which they arrived from Britain, France, Italy, Germany. Mexico or wherever. It poured with rain and was grey and miserable but on Friday morning when practice began the sun was shining from blue skies and it was comfortably warm. “It won’t last” everyone said, but it did and it was even better on Saturday, but Sunday — oh dear!

The circuit in Montreal is laid out on the service roads around the othibition park on the long, thin island in the Sr. Lawrence river known as Ile Notre-Dame, connected to the Ile Ste. Helene by two bridges and from thence to the main part of the town by another bridge and the Underground train, or Metro, Montreal being essentially French-speaking and Franceorientated. Although the circuit is virtually flat, with two tight hairpin bends and some wiggly bits through ess-bends which are virtual chicanes, it also has some fast bits and the elongated ess over a blind brow that follows the short straight past the pits is particularly challenging. The average speed for the lap record is over 110 m.p.h and the whole thing is not at all bad. The race is sponsored by the Canadian brewery Labatt, who have been brewing beer since 1828, and the city of Montreal really went out of the, may to publicise the Grand Prix.

Qualifying

Like Long Beach and Monte Carlo there can be no pre-practice testing, for the roads are only closed for the three days of the Grand Prix, so when the track was opened on Friday morning everyone was ready to go and there was a noticeable difference in the tempo during the first hour. Everyone seemed to be fogging round and round without stopping, leaving the or Ian, remarkably empty, save for the odd T-car here and there. They were all out on the circuit remembering what they did or did not do last year, or learning it for the first time. There were no startling changes to be seen, though most people had bigger air scoops to the brakes, or bigger discs, or more calipers and so orti for brakes are pretty important on this circuit and come in for a good hammering. Williarns were actually playing around with water-cooling for the brakes on their FWO7C cars, as Renault had done two years ago.

The Arrows team were endeavouring to cash in on it being “local hero time” by dropping Siegfried Stohr from their team and signing on Jacques Villeneuve from nearby Quebec, though more importantly, he is the young brother of the famous / infamous (to taste!) Gilles Villeneuve, otherwise it was the same faces in the same places and in the same cars, except that Williams brought alang their test-and-research car as well as their usual three cars, Piquet had a brand new Brabham, number 15, Watson had a brand new McLaren, number 4, Mansell was using the latest Lotus 87, number 5 winch was finished off at Monza, but not used, and Prost had the hest Renault mods yet (see Notes on the Cars).

Suddenly a red flag appeared at the start / finish line and everyone stopped. Brian Henton had spun his Toleman-Hart, stalled the engine, could not restart, and the car was stuck snake middle of the track on the back leg. With 29 other cars circulating the 2 3/4-mile track the passing traffic was too busy for marshals to retrieve the car or restart it. What most drivers were discovering very quickly was that this year’s generation of hard-sprung “go-karts” were finding bumps on the circuit that did not exist last year. Apart from the unpredictability of the way the cars bounced around, many of the drivers were suffering physically in their back and their neck muscles and everyone felt that the sooner the designers used some common sense and stopped cheating the spirit of the regulations, the better it would be for everyone and racing car design might progress forwards a bit, instead of sideways as it is doing at the moment. Before the end of the morning session Pironi “bounced” off the road into the wet and soggy run-off and the car came back on the breakdown lorry looking like an autocross car.

Hometown hero Gilles Villeneuve could only qualify 11th for Ferrari

Motorsport Images

Due to the morning delays the afternoon timed-hour was late in starting, but once under way everyone was hard at it, for no-one believed it would stay warm and dry for the next day of qualifying, so it was now or never as far as grid positions were concerned. You did not need to look twice to see that Nelson Piquet was out to win. He was driving the Brabham T-car with its carbon fibre brakes and they were glowing bright orange as he braked really late and hard for the hairpin before the pits. Laffite was also in a hurry and elbowing his way past slower cars in a pretty ruthless fashion, causing Serra to spin his Fittipaldi on one lap as he obviously thought “if Laffite can take the corner at that speed, so can I” — he couldn’t. Reutemann, Jones and Laffite all changed to their spare cars during the afternoon, either because they preferred the feel of it, or because it had a different suspension and aerodynamic set-up, all striving to get the best as soon as possible. Arnoux changed to the spare Renault, but he had little choice, for the RE33 arrived back at the pits with oil and water all over the car and very little of it where it should be. Pironi went off the road again and bent his Ferrari, and as Villenanve was out in the spare car the Frenchman ended his practice sitting on the pit wall. Rebaque was in trouble with his gearbox, so blocks were fitted to the pedals of the spare car after Piquet had finished with it and the Mexican went out in that for a few laps. Henton was out in the spare Toleman-Hart while mechanics fished for a broken-off end of a helicoil from a sparking-plughole thread in the monoblock Hart engine in his race car. They finally found it in the cylinder with the aid of a demon optical-fibre probe that the Renault team lent them.

Altogether it was a pretty busy hour, probably be it was everyone’s first opportunity to go fast on the circuit, with no pre-race testing and with the added incentive of the possibility that the sunny afternoon was but a fleeting moment in a continuous rain belt. The outcome was that Piquet made fastest time, which was no surprise after watching him out on the circuit, aid Reutemann and Jones were hard after him, these three being the only drivers to get below 1 mm. 30 sec. They were not only in a class of their own, but a ridiculously long may ahead of the fourth man, who was de Angelis in his Lotus 87, with 1 mm. 31.212 sec., two whole seconds slower than Piquet.

Rebaque was well up in fifth position, which team-owner Ecclestone put down to the fact that for once the Mexican arrived at the circuit fresh and awake, having come easily up from Mexico, rather than arriving after the trans-USA and trans-Atlantic flight from his Mexican home. There were not too many surprises down the list, most drivers being where you would expect them to be at this time of the season. Local hero Jacques Villeneuve was not exactly causing any interest, apart from a spin or two, and spent a lot of time in the pits having the water system on his Arrows purged to try and overcome continual overheating, basis made little appreciable difference. The Renault team were in engine trouble caused by a new design of injector nozzle not sealing properly and the leaking fuel causing mixture weakness, but in spite of this Prost was up ahead of the Ferraris.

Unbelievably Saturday was another fine and sunny day, with a lovely autumn nip in the air first thing, but it heralded rising temperatures, which confused all those who were expecting the worst. The morning test-session saw all the usual with various various brake temperatures, various aerofoil angles, and variations on all the other varuibles, in the attem% income up with the magic combination that spells success. To sort out their injector problem!, Renault tried Arnowes car with them mounted in the normal position, inside the vee, and Prost’s car with them in the new position, outside the vee. Eventually they settled on the old-type injectors in the new position, all this being in the search for better pick-up from slow-speed corners, which was coupled with smaller turbines and the same site compressors as before. The Talbot drivers changed cars, in their search for the best for Laffite, but soon changed back again, all of which Patrick Tambay accepted philosophically. Pironi’s car was in trouble with its fuel pressure system, so he went out in the Space Ferrari, the Ensign stopped after only one lap when its fuel pump went on the blink and young Villeneuve spun his Arrows and damaged the nose. Everything seemed to be going normally.

Now that the second qualifying hour was warm and dry and not wet and impossible as everyone anticipated, it called for renewed effort from everyone, for Friday’s times were no longer important. The three front runners, Piquet, Reutemann and Jones all set off in their T-cars, the first because the spare Brabham is something of a “qualifying special” and the two Williams drivers in order to save some wear and tear on their race-cars. The pace was hot all right and serious, and rather than swanning round saying “after you, old chap” it was possible toter a really hard bunch of hooligans having a good old go at one another, with no holds barred. Traffic Prnblems were had at the best of times, with thirty, drivers trying to get twenty-four places, but there was also quite a bit of healthy inter-team rivalry and some pretty deliberate baulking and carving-up among the top runners. Such tactics the top drivers against the lesser lights or newcomers, is not on, but among themselves is completely valid and perfectly-safe because they all know the score. Reutemann was at his ruthless best, driving with that hardness that will intimidate the most brave-hearted, and he actually beat Piquet’s best time of the afternoon though it was not as fast as the Brazilian had gone the day before. Jones was simply Jones.

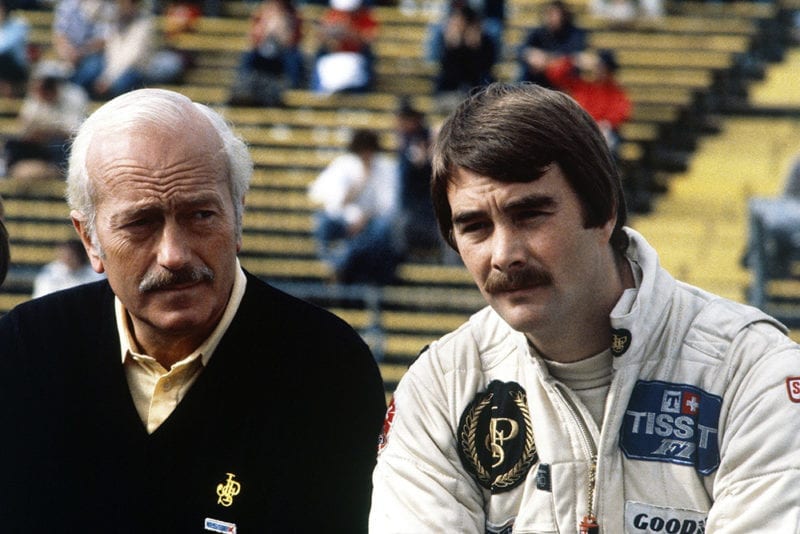

Lotus boss Colin Chapman with his young charge Nigel Mansell, who qualified 5th

Motorsport Images

Retiring at the end of the season or not, he was driving his hardest, and these three dominated once again, but joining them in the elite group in the under 1 min. 30 sec. bracket was Prost in the Renault and the enthusiastic Mansell in a Lotus 87. At the height of the battle among the top runners Piquet was on the receiving end of some track-craft by Arnoux, which incensed the little Brazilian who was determined to go again near the end of the hour and “foul up” Prost, who was beginning to go too fast. By this time one of Piquet’s rear tyres was a bit worn out, and he had no more available, so Mr. Ecclestone let the mechanics put one of Rebaque’s tyres on the back of Piquet’s car. As all the tyres are marked before each qualifying hour, with the driver’s racing number the eagle-eyed Reutemann saw this. Car number 5 had a rear tyre marked number 6. Oh my! Cheating! Rules, regulations, numbers, restrictions, red tape. Did I say practice in 1981 was a farce? There was something of a subterranean fuss caused by Mr. Ecclestone’s team being caught cheating, but an equally subterranean smoothing-over merely ended in a reprimand and a slap on the wrist, with any times recorded by Piquet on his odd rear tyres being removed from the list. Presumably the real reason he went out so equipped, to get one back on the Renault team, did not come up, otherwise the safety-committee and the do-gooders would have wetted their knickers.

This delayed the publication of the Saturday afternoon times by some hours, but when they appeared all was well, and combined with Friday’s times the starting grid was drawn up, with Piquet on pole-position, Reutemann next and pretty close, good old Jonesey-boy next, then the remarkable Mr. Prost in the Renault, followed by Mansell, Rebaque, de Angelis, Arnoux, Watson, Laffite, Villeneuve and the rest, the qualifiers ending at Salazar with the Ensign. Those left out were the two Fittipaldis (Rosberg and Serra), the two Toleman-Harts (Heaton and Warwick), the young Villeneuve (Arrows) and the rather despondent Gabbiani (Osella) who is beginning to realise that he is not going to make the grade in Formula 1. The qualifying hour had been enlivened by Gilles Villeneuve flying off the road in the high-speed ess bend after the pits, which in itself was not new, but his explanation was. He had gone as fast as possible on his first set of regulation (marked) tyres and then went out on his second set. Things seemed to be going well so he tried harder, convinced that he could take the bends after the pits without lifting off and could see making a time that might even get him near to the front-running elite bunch.

In simple words, he overcooked it, hit the kerb in the middle of the esses and spun, bouncing off the guard-rail to land up on the grass dishevelled but unhurt. He walked back to the pits to tell the Ferrari team he had goofed. As his second set of tyres were on the crashed Ferrari there was no way he could go out in the spare Ferrari, so that was that. You can’t say he doesn’t try. The most remarkable thing about the two days of practice was that Andrea de Cesaris did not crash his McLaren once, and still made a very reasonable mid-field qualifying time, the difference being that he usually crashes due to inattention or poor judgement, not through overstepping the ultimate limit, in an area where few drivers are able, capable or care to tread, unlike Gilles Villeneuve who lives in that area.

Race

We all knew it wanton much to hope for, that the sunny weather would continue, but there are degrees of cold and wet and nobody anticipated Sunday’s degree, nor the behind-the-scenes wrangling that nearly put paid to the race. On Sunday morning it was pouring with rain and the first change in the programme came with the postponement of the National motorcycle race that should have been run at 9 a.m. The Formula One warm-up half-hour was due at 11.25 a.m. but when that time came there was an official car parked at right-angles across the pits exit road and no engines were running.

Carlos Reutemann leads at the race start

Motorsport Images

Since the teams arrived in Canada there had been underground rumblings going on about the insurance cover for the event and the fact that it did not conform to the requirements as laid down in the Concorde Agreement. Public-liability and third-part cover was in order but there was disagreement over the insurance for the drivers and the teams in respect of claims against the organisers. This all blew up on Sunday morning as some of the drivers! teams had not signed a waiver dealing with certain aspects of the insurance, and without their signatures the overall insurance was invalid, and the race could not take place without insurance cover. For something She six hours legal wrangling went on between the organisation and Bernie Ecclestone, representing the teams. 11.25 a.m. came and went and nothing happened. 11.55 a.m. came and went, that being the time warm-up should have finished, to give the minimum of 1 hours before the start of the race, though in this case the start was due at 2.15 p.m. Then 1 p.m. passed and still nothing had happened, though at least the rain stopped and for a fleeting moment the sun shone. 2 p.m. approached and still nothing happened, except that the Television people were nearly delirious, for they were about to go on the air for the 2.15 p.m. start and had all booked expensive transmitting time on a space satellite, time which would not wait. We all used to think that the great god Television was more powerful than Formula One, but we were wrong. Na insurance cover, no race, and Bernie and the organisers were trying to come 50 45 agreement over what was covered by the insurance and what was not.

Eventually agreement was reached and insurance was valid, but then came the problem of catching up on time. More argument over a proposed 3-laps of warm-up, which was settled by an agreed 15 minutes of warm-up, but by now it was gone 2.30 p.m. and the race should have been running for 15 minutes. At this point the rain was not coming down and the track was dry enough for everyone to go out on “slick” tyres, but barely was everyone out on the track than the heavens opened and drenched everyone. Pity the poor paying public who had sat through all this since about 8 a.m. and there were a lot of them, for the race had attracted a good attendance. By now the Television commentators were gibbering wrecks mouthing away into their microphones incoherently. The 24 competitors rushed in for wet-weather tyres and adjustments of roll-bars and aerodynamics to suit and then the 15 minutes was up. Now it was a question of how soon after the warm-up (or wet-up) could the race start. Luckily no-one had suffered mechanical disaster and Reutemann’s desire for a 2-hour break to psyche himself into race-condition was over-ruled. The rain was here to stay this time, so a new announcement was made.

From 3 p.m. to 3.10 p.m. there would be a further test-session to allow teams to adjust their cars properly for a fully wet race. At 3.15 p.m. the pit road would be officially re-opened to start the 20 minutes count-down procedure, which included laps round to the assembly grid, positioning of the cars, the parade lap behind the pole-position car and the final count-down for the start, which would now be given at 3.35 p.m., exactly 1 hour and 20 minutes behind schedule. It was officially declared that the race would be “wet” and that it would run for 70 laps as scheduled, or two hours, whichever came up first.

Mansell retired on lap 45 after a collision

© Motorsport Images

All the Michelin runners were on regular Michelin wet-weather tyres, of radial construction of course, but the Goodyear runners were dickering about between 13 and 15 inch fronts, and different tread patterns for the rear. The Williams team had hastily changed the spare car on to 13 inch tyres, which meant changing the brake disc assemblies to smaller ones to fit inside the smaller wheels, and Reutemann was dickering about over the choice, driving one can round to the assembly grid, climbing over the pit wall and then driving the other car round to the grid. With Alan Jones already there in his own car we had the unusual sight of three Williams cars on the grid! Eventually Reutemann settled for a combination of these-and-those on his own car and the spare car was wheeled away. Villeneuve was in the spare Ferrari, but otherwise all was remarkably orderly. The Avon-shod runners were thankful to the Avon boys who hand-cut treads onto the tyres, and the Pirelli-shod runners were equally grateful for merely having a supply of wet-weather tyres. Some of the non-qualifiers must have been grateful for being out of it all. Finally, everything was ready, the red light came on, then the green and they were off in the biggest cloud of spray you have ever scan. Reutemann got the jump on Piquet and led the pack into the first right hand bend, cut across for the left hander over the brow of the hill and was hugging the inside line as he came into my view. Round the outside of Reutemann came Jones, past into the lead, and as he sliced through the fast right bander leading on the first straight there was just time to see Piquet’s Brabham right up close under the Williams rear aerofoil, followed equally closely by Prost’s Renault. That was the moment that Reutemann gave up.

As he disappeared into the spray of Jones, Piquet and Prost, de Angelis went by and then it was total oblivion and all you could hear was the sound of racing engines on full song, disappearing into a solid wall of spray. They were earning their money this time and even the hint man deserved a bonus rake plunged head-long into oblivion, even the regulation red rear-lamps being invisible. Half way round that first lap Villeneuve bumped into Arnoux, sending him into Pironi’s Ferrari and while the Canadian continued on his way Arnoux was off the road and out of the race and Pironi was gathering himself up again, to finish the first lap in 21st position. Jones had a clear, but wet, road in front of him and was making the most of it, out to win, while Piquet was not going to let him get too far away. Prune was third, de Angelis fourth, Reutemann fifth, Laffite sixth, Mansell seventh, Tambay eighth, Watson ninth and Villeneuve tenth, and while they were on lap 2 the rain started again. Reutemann simply gave up and toured round, dropping down to nineteenth place.

The lads up the front weren’t giving up, there was a race on and that meant a race to be won and most of them were out to win it, especially Alan Jones. For five laps he, Piquet and Prost drew away but it was raining hard and the Michelin tyres were better in deep water than the Goodyears. It was no surprise but sad nevenheless for the Jones’ fans, when he spun off on lap 6, causing Piquet to take avoiding action, which let Prost by into the lead, followed by Laffite and Villeneuve. It put Jones right out of the running, but Piquet hung on to fourth place, even though the Michelin shod cars were pulling away from him. When Watson got by into fourth place it was obvious to even the most casual observer that the Michelin tyres had something the Goodyears had not got, and the rain was still pouring down. Tambay, Patrese and Salazar were all victims of the conditions ending up off the road and out of the race and the overall scene comprised a Michelin race with the Goodyear-shod Piquet hanging on to them by his eyebrows, and the rest in which Daly was going great guns in the Avon-shod March and pulling through the murk from 20th place on the grid an seventh in the race, just behind de Angelis in the Lotus 87.

Despite starting second on the grid, Reutemann finished 10th and three laps down

Motorsport Images

At the front Prost was unhappy about the feel of his brakes and was not prepared to take chances, apart from the unsuitability of the turbo-charged V6 to the impossible conditions. Laffite on the other hand, in second place, was in terrific form and the wider torque-spread of the Matra V12 was giving him a much easier time. He overtook Prost on lap 12 and the maybe went by and pulled away here, was another courageous driver out to win the Canadian Grand Prix regardless of the conditions. Two laps later Prost was down to third place and this time it seas the tenacious Gilles Villeneuve who forced his Ferrari past the Renault, the Ferrari engine popping and banging on part throttle opening, and not coming onto full song until he could floor the accelerator pedal, which was not often on the skating-rink of a circuit that was awash with running water in most places. Laffite was a joy to watch as he forged through the spray, the Matra V12 sounding perfect, and “Happy Jacques” making the most of everyone elses discomfort. Front next fell victim to Watson, but managed to stay ahead of Piquet, so the order settled for a bit. Laffite (Talbot-Matra), Villeneuve (Ferrari), Watson (McLaren), Prost (Renault) and Piquet (Brabham). In an incredible sixth place was Pironi (Ferrari) having pulled himself up through the field after his first lap delay. Daly (March) was leading the rest, having disposed of de Angelis.

On lap 19 Pironi got past Piquet and on the next lap he was past Prose, putting himself into fourth place, but before he could catch Watson the Ferrari engine blew up and that was that. He had only done 14 laps, and in the spray and confusion many people did not realise what a fantastic job he had done after his team-mate had caused him to drop to the back of the field on the opening lap. The rain had now stopped bucketing down, but it was still awfully wet. Jones had been into the pits entry a different set of tyres but the handling was no better and as he was now next to last, with no hope of going any quicker he decided to pack it in and try and dilute the water inside him with a glass of beer.

McLaren’s Andrea de Cesaris stayed true to season form by spinning off on lap 51

© Motorsport Images

By thirty laps a dry strip of track was beginning to appear in places and if this went on one could foresee the wet-weather tyres wearing rapidly and a rush to the pits for dry-weather tyres, but we need not have worried for the rain returned after a while. For five laps Laffite found himself snick behind Andretti’s Alfa Romeo, the American driver seemingly oblivious or disinterested in what was going on behind him, while on the drying track Watson gained on Villeneuve and got by the Ferrari on lap 37, into second place but a long way behind Laffite. Prose was still fourth, but Giacomelli ousted Piquet from fifth place, making it a clean sweep for Michelin-shod cars, the courageous Piquet still not lapped by the leader.

Lap times had been anywhere between 1 min. 50 secs. to more than 2 mins., so clearly the race was going to stop at 2 hours, long before 70 laps were covered. In spite of slight drying-out on parts of the track Villeneuve was unable to take advantage of it and dropped back, not enough for Prost to do anything about it but presenting no challenge to Watson who was firmly in second place and driving nice and smoothly. While lapping de Angelis, Villeneuve collided with the back of the Lotus 87, both cars spun and the Ferrari was away again with a flourish but with its nose aerofoil badly bent out of shape. It had been bent at an angle since the first lap incident with Arnoux and now it was totally useless, but Villeneuve pressed on where others would have gone to the pits to complain about the handling or to have a new nose cone fitted. He left de Angelis gathering himself up and not a little upset.

Alan Jones retired his Williams on lap 24 with handling issues

Motorsport Images

Of all the cars on the same lap as the leader, and there were seven of them, only Piquet was on Goodyear tyres, which says everything for his tenacity, but even so he could not fend off Giacomelli, who went by him and now even de Cesaris was looking for a way by the slipping and sliding Brabham. Meanwhile a dejected Nigel Mansell had gone to the pits to complain about the poor handling of his Lotus 87 and a flat front per was found, but at this point the road past the pits looked pretty dry so his car was put onto “slick” tyres on the assumption that it was drying out all round. This was a very wrong assumption and Mansell had not gone far before he spun helplessly off the track, and as the marshals retrieved the 87 from the wayside and helped it back on the track the rear aerofoil got badly bent out of shape. On his way back to the pits Mansell changed from one side of the road to the other just as Prost arrived and the Renault punted the Lotus up the back. A very angry Prost went off into the barriers and damaged the nose of the Renault and lost fourth place, while Mansell limped to the pits. This let Giacomelli up into fourth place, followed by a struggling Piquet and an excited de Cesaris, who could see fifth place was there for the taking. Behind them Laffite was waiting to lap them both and he watched spellbound as de Cesaris lunged to pass the Brabham, got it all wrong, the cars touched and while Piquet controlled a wild slide the McLaren was off the road and into the grass and mud. A slightly qurizical Lather then lapped Piquet and went on his way, soon to lap Giacomelli.

Villeneuve had been driving round with the battered front aerofoil of the Ferrari getting tattier and tattier, until the wind pressure broke the mountings and the whole thing folded up over the nose of the car, but still Villeneuve drove on. Peering round the side of the obstruction, for after all he was holding third place in this marathon of a race. Within a lap the battered aerofoil and the complete nose cone broke right away and flew over the cockpit, while the driver kept his head down, and one of the Ferraris rear wheels ran over the remains. With a clear vision once more but with very little holding the front wheels down on the road Villeneuve pressed on at unabated speed. The rain had started teeming down again and at times you wondered how he got the Ferrari round the corners when both front wheels seemed to be off the ground. But he was still holding third place.

John Watson finished 2nd in his McLaren

© Motorsport Images

As Laffite was on his sixty-third lap the two hour mark was reached, seas he finished the lap the chequered flag was waved and eleven very relieved drivers lifted off and toured round on the slowing down lap. Only Laffite, Watson and Villeneuve completed sixty-three laps, the rest being one lap, two laps and even three laps behind by this time. Chester (Tyrrell), de Cesaris (McLaren) and Prost (Renault) were all classified as finishers even though they had retired, as they had completed the required percentage of the winners distance to count as finishers. Cheever had coasted to a stop with engine failure and the other two were off the road. Next to last, of those actually going along, I can’t say racing, was Carlos Reutemann a sad and dejected figure and not exactly representing a potential World Champion driver. At the front of the finishers they were heroes all, and nobody begrudged Lather his win, he had really earnt it. — D.S.J.