Why practice made perfect for Moss and Jenks’ 1955 Mille Miglia win

Before their stunning 1955 run Stirling Moss and Denis Jenkinson had both competed separately in the Mille Miglia. Doug Nye unearths their diary entries revealing the lessons they learned along the way

Getty Images

Stirling Moss’s first experience of Italy’s tremendous classic road race came in 1951, upon his debut as a works Jaguar driver. He was only 21. He still had a head of hair. He was to drive a Jaguar XK120, a sister to the car in which he had sensationally dominated the RAC Tourist Trophy at Dundrod seven months before – on the drive which had earned him his new factory contract.

He was accompanied in the car by Jaguar mechanic Frank Rainbow and would write in his diary for race day – April 29, 1951: “Today is Mille Miglia day so up at 3am. Cold and wet. Went to start. Tremendous set-up, with thousands of bods organising things. Pouring rain when I left at 4.32am, 3 minutes after Leslie Johnson” – his works Jaguar team-mate. “Caught the Ferrari saloon which started 1 minute ahead in about four miles. Car going well considering, getting along at about 115mph, in darkness! Then after 15 miles it happened. Chap waved me down, applied brakes, nothing happened, turned wheel, same effect. On oil! Hit Fiat which Leslie and Ascari had done, and bent wing on to wheel. Went to garage and reversed, gearbox jammed in reverse, took 2 hours to repair. Also bonnet wouldn’t close, so had to retire, damn it.”

Motor Sport writer Denis Jenkinson’s Mille Miglia debut came in 1954, with HWM co-founder George Abecassis in command

GP Library

Frank Rainbow later recalled how he and fellow team mechanic John Lea had driven the two XK120s down from Coventry, with colleague Phil Weaver in a prototype Jaguar Mark VII, loaded with spares. They encountered only one problem en route, the new Mont Cenis Pass was blocked by snow so they had to pay what they had been trying to avoid – Sir William Lyons was always ‘careful’ with money – the train-freight fare through the tunnel from Modane.

Recalling this first experience of such an immensely challenging race Stirl would explain: “You couldn’t possibly learn the course, you just had to attack it like a rally special stage and go as hard as you dare, realistically driving at, say, seven- or eight-tenths maximum effort, all the way…”

Once readied for the race, Frank Rainbow found their XK120 occupied by two Italian tifosi whom he had to eject: “I think they thought it was Italian because it was red…” – having been painted originally for Nuvolari to pilot. The team stayed at organiser Count Maggi’s Calino residence, and after some practice mileage “Jack Lea and I were wrapping cord around the [rear] springs to stiffen up the rear ends to prevent bottoming under full tanks, standing in a pit about an inch deep in water… it was sweat we were standing in. It was mid-day and very warm…”.

Abecassis in his HWM-Jaguar, 1954; he drew a blank in the Mille Miglia this year, a third consecutive DNF.

GP Library

The accident site was at the Castiglione junction. Of young Moss’s driving Frank explained: “I had every confidence in him…We had passed a Ferrari and I noticed that Italy still had a lot of postwar repairs to do. We crossed one Bailey bridge at about 100mph and the sound was as if all the planks had upended themselves… we hit a Topolino parked where there would otherwise have been an escape road. As we got out to inspect the damage Jack Lea ran over from Leslie Johnson’s car…” – its fuel tank was crushed, its race over. Frank reset the Moss car’s throttle linkage. “We rejoined but Stirling found virtually no lock to the right… we overshot the first open garage…reversing proved our final undoing… the reverse gear bush seized on its idler shaft”. By the time he’d freed it, the first race control had closed – so the only option was to limp the battered red XK120 back to Brescia, only to wrong slot and find themselves at the top of a flight of stone steps. Mindful not to reverse, Stirling drove gingerly – bump, bump, bump – down them all and on, disappointed, to Jaguar’s Calino base.

Having covered so few of the thousand miles – and those largely in the dark and rainswept gloom – Moss had learned precious little about Italy’s great race. But he returned as Jaguar’s official No1 driver – in their latest disc-braked C-type – in 1952. “There we met the Mercedes works team of super-light 300SL Coupés…” who “…had been in Italy for months to learn the course, perfect their cars and to choose refuelling and service stations. Works test driver Norman Dewis rode with me and we set off in pouring rain at 6.19am… After a couple of hours the rain eased and finally stopped and we’d overtaken several good runners when a thump and a lurch… a thrown rear tyre tread. While we were changing it Karl Kling’s Mercedes went past, and he had started four minutes after us – which was worrying.

“I trailed him into the Ravenna control, and passed him soon after, then caught Caracciola’s 300SL and passed him, only to catch myself out going into a right-hander…”. After they had knocked down a line of marker poles Stirl regained the road, noting that Norman promptly “…used up a whole box of matches trying to light a cigarette.

“A dope in a Fiat opened his door just as I came haring in, and our Jaguar chopped his door off”

“We lay seventh in Rome but the rear dampers had gone and the fuel tank was leaking… Stopping for more fuel in Florence a dope in a Fiat opened his door just as I came haring in, and our Jaguar chopped his door straight off. Norman picked it up and handed it back to him, but received no thanks”. The owner of the Fiat, Francesco Coppola from Salerno, wrote later demanding that Moss pay for the damage. Jaguar settled for £17 14s 5d.

Moss: “Unknown to us, we were virtually assured of fourth place… until on the Raticosa Pass with only 145 miles to go I lost the front end and understeered into a rock. This broke the steering rack away from the frame, so with steering gone, dampers gone and fuel tank split we had to retire.”

Jenks’s diary, May ’54

GP Library

By 1953 Stirling had the stature to push Jaguar hard for proper pre-race reconnaissance before his third Mille Miglia. He was supported by Angelo Chieregato of the Compagnia Generale Auto, Jaguar’s Italian importer. But the works-entered C-types did not arrive until the weekend pre-race. In assorted touring cars Moss claimed to have completed some 6000 miles all within two weeks. Veteran of 10 Le Mans 24 Hours Mort Morris-Goodall had been engaged as Jaguar’s team manager. He would ride with Moss, but as Jaguar historian Andrew Whyte explained: “…the axle failed shortly before the first control at Ravenna, the tube twisting in the differential housing, so Moss’s Mille Miglia score so far was a miserable zero finishes out of three attempts”. Andrew continued “…wisely Jaguar did not attempt to win the Mille Miglia again” – Sir William quite happy to win Le Mans five times instead…

Stirling Moss attended the 1954 Mille Miglia, without a drive. But his fearless future navigator – Motor Sport’s Continental Correspondent and 1949 motorcycling World Champion sidecar passenger – Denis Jenkinson did, sharing the works HWM-Jaguar’s cockpit with team principal George Abecassis.

The opportunity, he wrote: “…of satisfying a schoolboy ambition, to ride as a racing mechanic in the most fantastic of all races” and to “…sample the 150mph speeds that are spoken of lightly by people ‘in the know’ was overwhelming”. And George Abecassis had offered him the chance to scratch both itches.

As background to that 1954 race, Jenks had already been touring around Europe for five jam-packed weeks, covering for this magazine such races as the Giro di Sicilia, and the Syracuse, Pau and Bordeaux Grands Prix.

“I was conscious of being in a realm about which I had no experience and the feeling was odd”

To place his Mille Miglia debut in context, consider that he wrote his Pau GP report on the evening of race-day there, Easter Monday, April 19, before setting off for the following weekend’s Coupes de Paris sports car fixture at Montlhéry. His diary entry for Saturday April 24: “All day at Montlhéry for practice. Guy Mairesse killed in Talbot. Quiet evening on own.” On Monday 26th, he drove back south to Saint-Étienne and the Planfoy hill-climb in which he competed in the hard-pressed “but ever willing” Aprilia. On the rainy Tuesday he headed back through the Mont Cenis tunnel for a “very wet run to Brescia by dark. Supper with [Peter] Scott-Russell” (who was co-driving Dick Steed’s private Lotus Mark VIII). Next afternoon Jenks drove to Count Maggi’s home at Calino where he met “Abecassis & HWM…”.

Friday April 30: “All day in Brescia. HWM weighed in. Still raining”. He met the spectating Stirling Moss before “…early evening after taking Moss & sister to Calino”. There, as he later reported, the HWM mechanics added: “…a few details… such as drinking bottles with long rubber pipes, a bracket made to keep a tin of sweets and some oranges in place, a block of wood on the floor for me to brace my feet against, a little bungy rubber padding, a second hand-hold on the tail of the car, and we were then ready for a trial run on the Autostrada.”

Saturday, May 1: “Went to Calino. Run to Brescia & back in HWM 5300 in top along Autostrada 143mph. Rest of day tinkering about at Calino. Home & bed by 9pm”. The HWM was geared for 26.9mph per 1000rpm in top gear and Jenks wrote: “I was very conscious of being in a realm about which I had no experience and the feeling was odd to say the least, and I began to pay very close attention to all about me. Then some traffic appeared and we were back to a cruising 100mph. Yes, I was quite certain I was going to enjoy the Mille Miglia.”

Moss and Mort at the 1953 Mille Miglia sign-in with their works C-type – Stirling’s third and final Mille Miglia with Jaguar

Getty Images

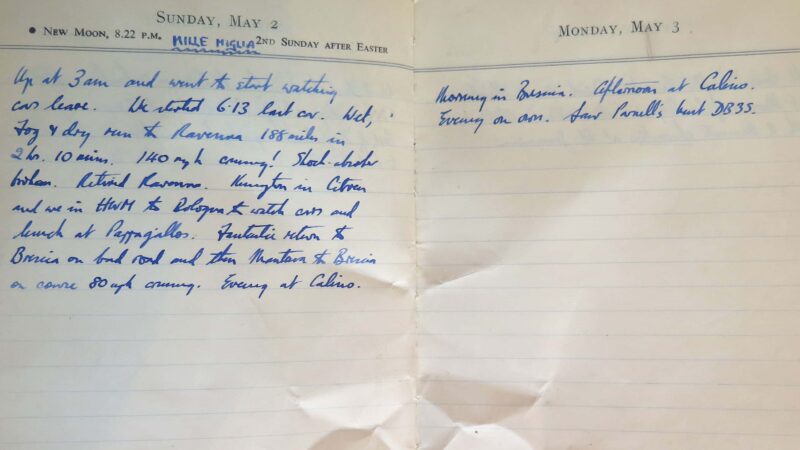

Sunday, May 2: “MILLE MIGLIA – Up at 3am and went to start watching cars leave. We started 6.13 last car”. Accelerating away from the starting ramp provided another new experience: “In front of us was a solid block of people but Abecassis had done many Mille Miglias and he just drove straight at them with the speed rising to 80 and 90mph. When they were petrifyingly close the crowd swayed back to let us pass… for the next 20 or 30 miles… they always moved aside in time. The greatest difficulty was that it was impossible to see any of the corners… and I thought how infuriating it must be to learn the course on a normal day and then try to remember it under these conditions. Out of Verona the road ran dead straight but was lined with people… and at 140mph we drove through this sea of ‘ants’ with only a three foot space on each side of the car”.

Later “…for mile after mile we cruised at 142mph…” but “In Vicenza the road was very bad and on one corner we hit a bump which threw us almost onto the pavement, the crowd stepping smartly backwards as one man”. Back up above 120mph, they found the car wandering. It became clear something had broken, probably a damper. Beyond Padua a mist enveloped the course for 15 miles. As George bubble-footed, the engine lapsed onto seven cylinders. After Rovigo a two-mile section washed away by recent floods had been replaced by “a loose cart track”. Losing time, they were caught and passed by Tom Meyer’s Aston Martin, which promptly crashed in front of them. “Thinking very deep thoughts about tyre adhesion we continued on our way. Eventually we arrived at Ravenna, had our card stamped and pulled over to our pre-arranged pit. The misfire proved to be something obscure in one of the Weber carburettors… the damage was the complete end of one of the shock absorbers broken off and quite irreparable. We were the last starter and they had allowed us a certain measure of time and [would] then consider the event finished. We had got behind this time allowance and it was going to be impossible to regain it. As we were now 20 minutes behind schedule, with no hope of making up any time… it was decided to retire. We had covered 200 miles and for us the race had hardly started; there was another 800 miles to cover, so we removed our crash-hats, and went and had coffee”.

In his diary he wrote: “Wet, fog & dry run to Ravenna 188 miles in 2hrs 10mins. 140mph cruising! Shock absorber broken. Retired Ravenna. Kennington in Citroen and we in HWM to Bologna to watch cars and lunch at Pappagallo’s. Fantastic return to Brescia on back road and then Mantova to Brescia on course 80mph cruising. Evening at Calino…”.

Jenks finished his report: “For the 200 miles from Brescia to Ravenna we averaged 87mph, and that was too slow to justify continuing – a solemn thought indeed…”.

That Tuesday saw him drive his hard-pressed 1939 Lancia Aprilia up to Modena, visiting Maserati and finding Moss there about to test his brand-new 250F. Jenks would have been bubbling with Mille Miglia experience. He and Stirling compared notes. Stirling’s subsequent exploits in that Maserati 250F grabbed Mercedes-Benz’s attention. They signed him for their two-pronged 1955 programme aimed at both the Formula 1 and Sports Car World titles. First sports car race would be the Mille Miglia. When Stirling was asked to suggest a passenger, guess who he suggested?

With benefit of Jenks’s experience in ’54, combined with Moss’s from 1951-52-53, plus the capabilities of Mercedes-Benz, they would win the Mille Miglia outright, at that stupendous record average speed – for 1000 miles – of 97.98mph.