British Hillclimb Championship: Racing against the clock in its purest form

The British Hillclimb Championship is an often overlooked gem that’s brimming with engineering ingenuity and on-the-limit commitment. Paul Lawrence looks at what’s in store for the ’24 season

Alex Summers is alone among the British Hillclimb Championship front-runners to drive a DJ Firestorm. He scored a run-off win here at Shelsley Walsh last August

Paul Lawrence

The long-running British Hillclimb Championship can proudly boast to pre-date every other British motor sport title. It first ran back in 1947 and this year will be its 77th season, with only the 2020 Covid pandemic stopping an unbroken run. It started before British Formula 3, British Touring Cars and the British Rally Championship and remains as fiercely competitive as ever.

Remarkably, there are very few rules for top-flight hillclimbing where 420kg, 700bhp projectiles teeming with electronics create an incredible spectacle on the 10 hills visited during the British Hillclimb Championship.

Will Hall – championship runner-up in 2018 – charges through the farmyard at Harewood in the Gould he ran new for 2023

“This is driver and machine, and the spectacle is amazing”

Aside from some basic rules about the overall dimensions of the cars, there is little to hinder engineering ingenuity and driver talent. There are no pitstop penalties, no DRS, no success ballast and no driver grading. This is driver and machine against the clock in its purest form and the spectacle is amazing.

Standing firmly at the top of the hillclimbing tree are the over 2-litre single-seaters that usually set the pace in the British championship. However, that is just the tip of the iceberg for this branch of the sport and hillclimbing is truly a broad church with competition to suit all tastes and pockets. Beneath the over 2-litre cars are single-seater classes split at 1100cc, 1600cc and 2 litres. The fastest will be in the hunt for points in the top 12 run-offs that are the pinnacle of any British Hillclimb Championship round.

Wallace Menzies is the Max Verstappen of the Hillclimb Championship – number one every year since 2019

On their day, the best of the smaller-engined cars can get up among the big bangers, but that task gets harder and harder as the years go by. Changeable weather will give the smaller engine runners their best chance of overall glory but it still takes massive commitment to get an under 2-litre car into a run-off. In 2023, only Paul Haimes and David Warburton forced their Hayabusa-engined Goulds into the final championship top 10.

Typically, the smaller-engined cars rely on motorbike engines and the 1600cc Suzuki Hayabusa is a popular choice. When packaged into one of the purpose-built hillclimb cars from specialist constructors like GWR, OMS, Empire, Force and DJ, the result can be as much as 400bhp propelling as little as 330kg.

Gould Racing

Gould Racing

Long ago the over 2-litre single-seaters tended to be out-of-favour circuit racing cars but the era when March, McLaren, Brabham and McRae provided the weapons of choice ended in the late 1970s. For more than four decades, Pilbeam and Gould have dominated the top of the sport and Roger Moran was the last champion in a Pilbeam back in 1997. Since then, 22 of the 25 titles have been won by Gould, a run only broken by three excellent titles for Trevor Willis in his OMS.

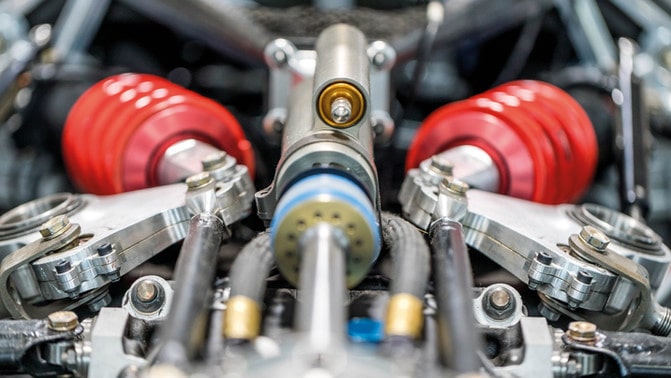

With the last four titles under his belt, Wallace Menzies is the man to beat and his Gould GR59 is the state-of-the-art hillclimb car of the moment. The purpose-built carbon-fibre tub is propelled by a 3.3-litre Cosworth XD Indycar engine using an Xtrac six-speed sequential gearbox with paddle shift. A complex launch and traction control system stops the wheels spinning most of the time by monitoring the relevant speeds of the front and rear wheels.

Gould Racing

Gould Racing

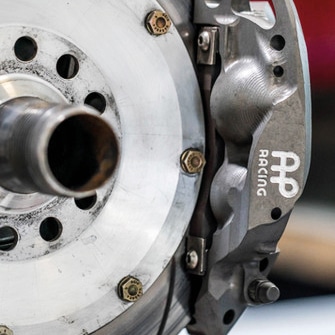

An extensive aero set-up completes the package, with complex multiplane front wings. Even though the car is frequently operating at speeds between 25mph and 100mph, downforce remains an important element of performance.

This season, most of Menzies’ chief rivals will also be Gould mounted as Matt Ryder and Sean Gould share a GR59 and Will Hall fields his own GR59. Missing from the mix will be six-time champion Scott Moran, runner-up last year in Graham Wynn’s GR59, as Moran steps back from competing at this level. While Menzies relies on the 3.3-litre Cosworth XD, the late 1990s Indycar power unit, Ryder, Gould and Hall have all opted for the slightly newer 4-litre Le Mans engine developed by Judd at the turn of the millennium. Meanwhile, Alex Summers goes his own way with a DJ Firestorm chassis fitted with one of the incredibly successful Ford Cosworth V8 Indycar engines, developed in the late 1970s. At 2650cc it gives away some power to its rivals but offers tremendous driveability as it revs as high as 14,000rpm.

Trevor Willis’s OMS has a 3200cc engine; to win the title you need an engine in excess of 2 litres

Gould Racing

Trevor Willis is another who tends to lose out when power is all with the 3200cc RTE unit in his OMS 28. The engine is effectively two 1600cc Suzuki Hayabusas mated together and Scary Trev’s renowned commitment and car control can often go a long way to making up the power deficit. Dave Uren and Nicola Menzies share an older Gould GR55 with a 3.5-litre Nicholson McLaren V8 engine, another unit with its origins in Indycar racing. For many years, the NME XB V8 was the engine to have on the hills but it takes all of Uren’s fierce determination to get it up into the top results these days. Nicola, wife of Wallace, is equally committed and is a regular run-off contender.

Rounding out last year’s top 10 were the smaller engined Gould GR59s of Paul Haimes (1300cc turbo Hayabusa) and David Warburton (1600cc Hayabusa) while knocking on the door this year to try and get a top 10 number for 2025 will be young Jack Cottrill in his 2650cc Indycar-powered Dallara and Richard Spedding in his 1600cc Hayabusa-powered GWR Raptor 2.

Matthew Ryder –a serious challenger to Menzies – driving at the 2023 season opener at Prescott

Ben Lawrence

Menzies and Ryder will be two of the biggest contenders when the 2024 season kicks off amid the spring blossom and bluebells at Prescott.

Menzies, aged 50, is a supplier to the construction industry from Alloa in Scotland. “We’ve got the same package as before with the 3.3-litre Cosworth engine,” he says. “We’re going to go from eight injectors up to 24 which should give us a bit more on the straights. I last ran that set-up in the DJ in 2014.

“The dream and ambition is to do as well as we can and it’s going to be as hard as ever this year. After 2019, winning the first championship, you’ve almost got to then reassess what you’re doing it for, because that had always been the dream.

The hillclimb ‘Class of 2023’ – Menzies is nearest

Ben Lawrence

“If you’re doing this just to win a championship, good luck to you”

“But I’ve hillclimbed since 1998, and I really, really enjoy it and I love the sport. And that’s why I’m doing it. If you did it just to win a championship, good luck to you. But I couldn’t do that. I’m not doing it for that. I’m doing it because I really enjoy the sport and the people.”

Ryder, aged 28, is an operations consultant from Oxfordshire. “To be honest, it is much the same from me for 2024,” he explains. “Same car, same driver pairing with Sean Gould. I’ve been really happy with my improvement over the last couple of years.

“I love the fact that you get one chance to make it happen. You have to judge the speed with no lap after lap practice to build up to it. I did a bit of circuit racing earlier in my life and loved it, but this is a challenge that you really have to do to understand.

Going for Gould – the paddock at Shelsley

Ben Lawrence

“The adrenaline rush of getting it just right on the one run when it counts is something quite special. And then you mix that with the paddock environment which is lovely: the camaraderie with other drivers that you don’t get in other forms of motor sport. Hillclimbing becomes something quite special.”

The famous hills of Shelsley Walsh, Prescott and Doune are at the heart of the calendar and are joined by trips to all corners of the UK. From Wiscombe Park in Devon to Doune in Scotland, Craigantlet in Northern Ireland and Bouley Bay and Val des Terres in the Channel Islands this truly is a British championship, and mounting a serious title assault requires significant commitment.

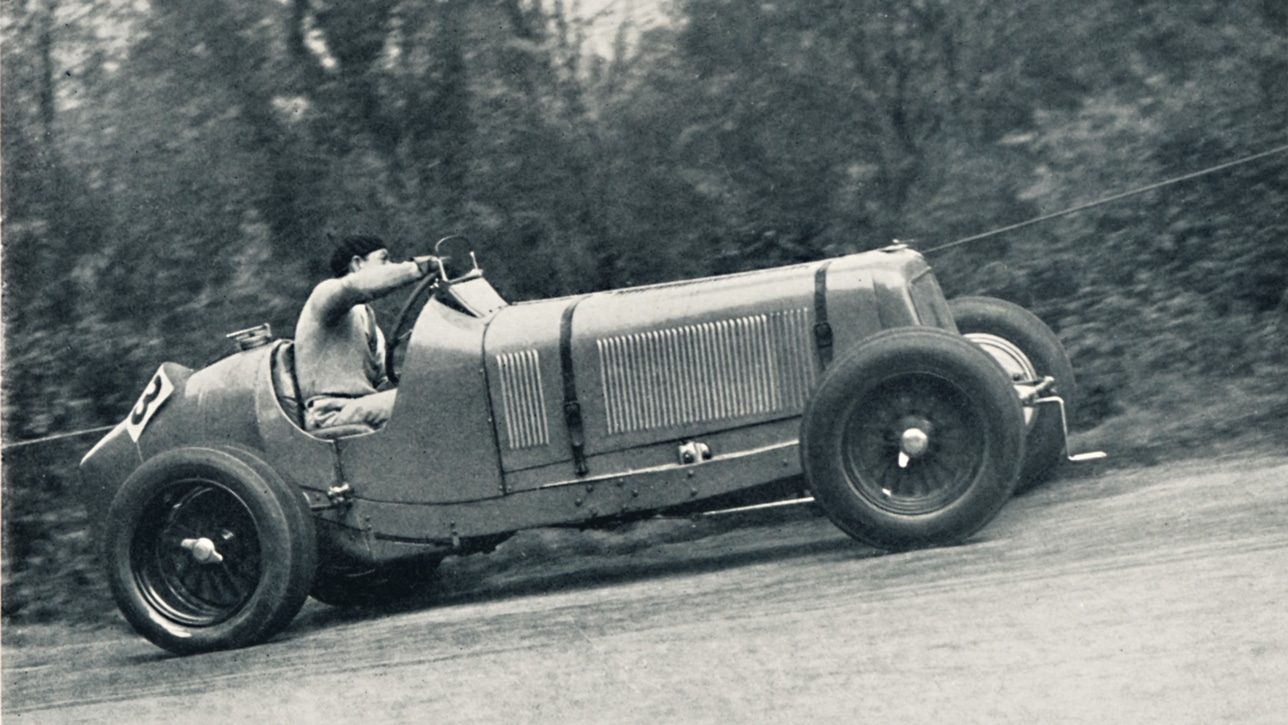

Hillclimbing is steeped in history and Shelsley Walsh is the oldest, having been in use since 1905. Only two world wars have interrupted the Shelsley story. Prescott dates back to the late 1930s and other hills have a long history. Bouley Bay and Craigantlet joined Prescott and Shelsley Walsh in the inaugural five-round championship in 1947 alongside the Bo’ness climb in Scotland.

But Shelsley Walsh remains the place where everyone wants to win. The 1000-yard adrenaline rush up the side of the Teme Valley in rural Worcestershire is narrow, fast and challenging and the place just oozes history and atmosphere.

Trevor Willis bottoms-out his OMS

Ben Lawrence

In the summer of 2021, Sean Gould finally broke the hill record that had stood since 2008 when he catapulted his Gould GR59 to the top of the hill in 22.37sec to claim one of the sport’s biggest accolades.

In August 1905, Ernest Instone and his three passengers urged their 35hp Daimler to the top of the gravel hill in 77.6sec. In 1935, Raymond Mays took his ERA R3A under 40sec and in 1971 David Hepworth broke the 30sec mark in his self-conceived four-wheel-drive Hepworth-Chevrolet. In August 2021, once he’d studied his data, Gould admitted that a run in close to 22sec was feasible.

“Shelsley Walsh is the place where everyone wants to win”

While Shelsley is all about power and commitment, hills such as the spectator-friendly Prescott, Harewood, Wiscombe Park and Loton Park reward measured commitment as well as explosive bursts of power. Doune is all about accuracy and has been described as being like Shelsley Walsh but without the run-off. Craigantlet, Bouley Bay and Val des Terres differ from the mainland hills in being temporary courses on closed roads.

Raymond Mays breaking the Shelsley Walsh record in 1935

Getty Images

Bouley Bay is noted for its lack of grip from wind-blown sand and the traction control systems on the big cars are chattering away for much of the twisty 1011 yards. Val des Terres, the shortest hill on the schedule at just 850 yards, demands precision as it dives across specially lowered pavements on the climb up from the seafront at St Peter Port.

With such a diverse range of hillclimb venues, each of the leading contenders will have their favourites as well as those where they just don’t click. Unusually, Gurston Down starts with a downhill run to a 120mph sweep along the valley before the very slow speed Carousel section and then another high-speed rush to the finish line. Along with Bouley Bay, Prescott is one of the slowest hills but packs a lot of challenge into 1128 yards. At 1584 yards, Harewood is the longest and includes the famous charge between the buildings in the farmyard.

Graham Wynn’s Gould had the largest engine in the field at Shelsley Walsh in ’23 – a 4000cc Judd. He’d end the season in 15th position

Paul Lawrence

Hillclimbing has much to commend it to competitors, both current and future, and spectators. For the drivers, the intense concentration and adrenaline rush keep them coming back to a sport where camaraderie and friendship are central to the experience. Tools, equipment, spares and even whole cars are readily loaned to those with problems.

For the fans, there are some fabulous venues and access to cars and drivers is way better than in just about any branch of the sport. The spectacle of the top cars being driven on the limit is awesome and the competition is intense. At 77 years of age, the British Hillclimb Championship is as good as it has ever been.