Senna Siempre: How Ayrton’s dream to tackle poverty was made reality

Before Ayrton Senna died, plans were drawn up to start an organisation that helped Brazil’s impoverished children. Rob Widdows speaks to the driver’s relations who saw that vision through

Getty Images

The Instituto Ayrton Senna was set up in the months after the triple world champion died at Imola in 1994. A small team of people led by his sister Viviane, pictured on the previous page, and his niece Bianca, have since dedicated themselves to building bridges across the canyon that divides rich and poor in Brazil.

In 2008 I spent a week in São Paulo, seeing at first hand the work of the institute in and around the city as well as further afield. Having been to the Grand Prix at Interlagos over the years I had become aware of the challenges facing the institute. The circuit sits by a favella on the edge of São Paulo, a tumultuous city that is home to more than 13 million people.

This month, as we mark the 30th anniversary of Senna’s death, I re-visit the story, bringing it up to date with Senna’s niece Bianca, and reviving my conversation with Viviane, and those who knew him best.

Thirty years after the tragic accident at Imola the institute, established with funds from Senna’s legacy, continues to help stop Brazilian children from falling onto the scrapheap, from sliding into the oblivion of drugs, crime and life on the streets.

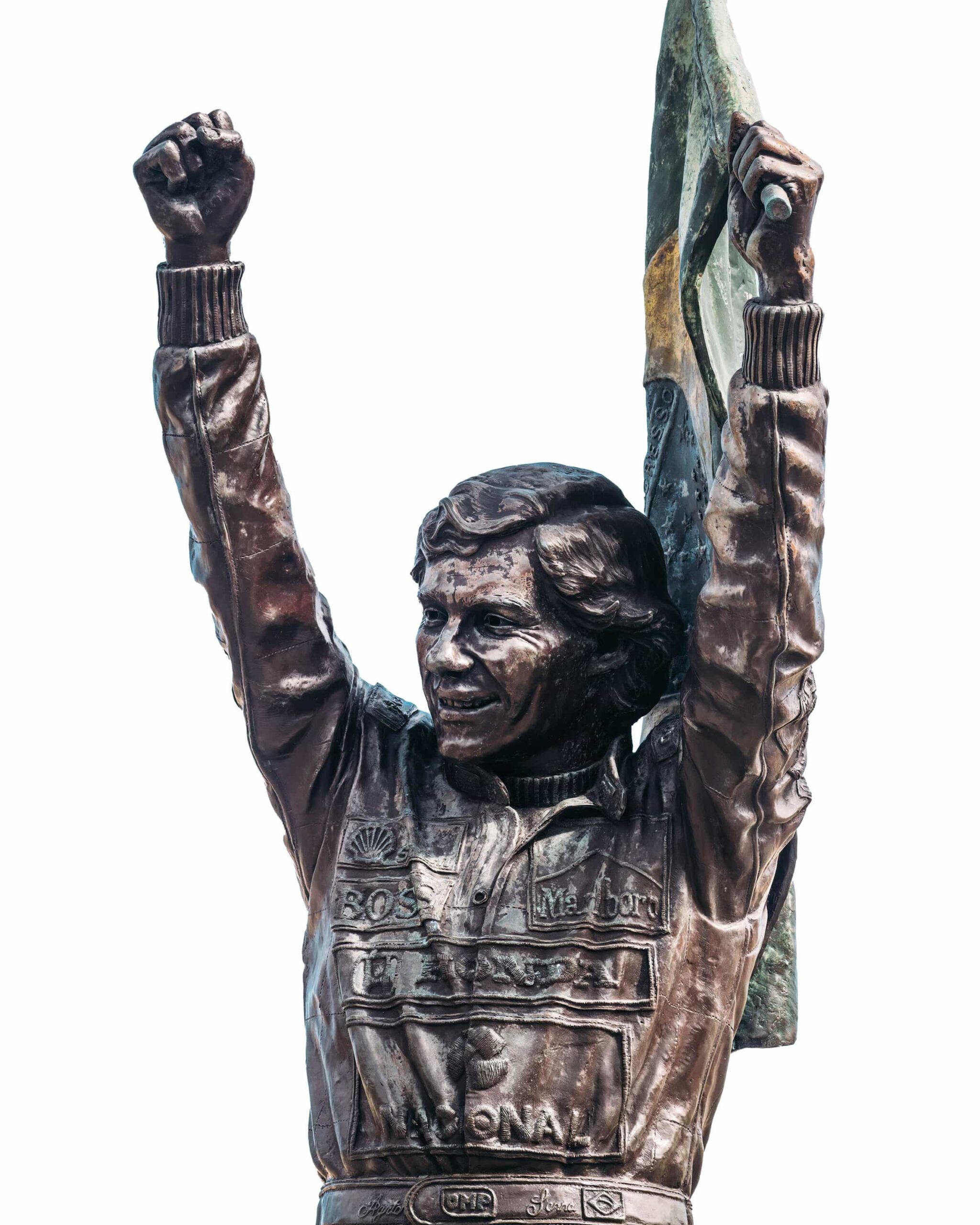

Life-size bronze statue on Copacabana Beach

For Brazilians Senna remains a god, the adulation expressed on posters and flags all over São Paulo. To the rest of the world he was a mere mortal with a miraculous talent. At once both ruthless racer and gentleman, ferociously ambitious and deeply caring, he was a committed Christian and a fiercely focused fighter with an overwhelming desire to win.

In the winter of 1993, and on into the early days of 1994, he was tired, worn down by business worries and the weight of his extraordinary success. He had some doubts about his decision to move from McLaren to Williams, the FW16 not yet to his liking, while Michael Schumacher in the Benetton was in the ascendancy. A man can only take so much and Senna was feeling the strain.

“Ayrton emerged as an inspiration through his success in Formula 1,” says Bianca, who is also CEO of Senna Brands, a company set up to manage Senna’s assets after his death and which diverts part of its revenues to the Senna Institute. “His victories became a source of pride for many Brazilian people. His racing, and his world titles, transformed him into a hero, symbolising the resilient spirit of a Brazilian who fought for his beliefs. His journey is a powerful example of the relentless pursuit of dreams and has left a lasting impact on millions of people around the world. Today this is what the Senna brand is all about… inspiring people to fight for their dreams and become the best version of themselves.”

An 11ft sculpture, created by Lalalli Senna – Ayrton’s niece – in 2022 overlooks Interlagos.

Comic-book Senninha.

Senna had already helped many individuals, privately diverting money to causes, or families, that had been brought to his attention. But these were single donations, responses to a crisis, or cheques written in the desperate hope that a part of his fortune might alleviate the misery of his own people.

“We knew, of course, that he had done this,” Viviane told me in 2008. “It was not an organised or planned thing, and he did not draw attention to it. Nothing was ever discussed or recorded in any detail. It was an emotional response to what he saw, what he knew, and what he was told or shown. But in 1994, just two or three weeks before the race at Imola, he was in some different frame of mind when he spoke to me, asked me to help him set up some kind of structured organisation, a charity if you like, to tackle the increasing poverty.

“Before the race at Imola he was in some different frame of mind”

“Children were always uppermost in his mind. It was always the children that he spoke about. He loved children, and he knew that unless something was done to improve their chances of a proper education they would have no future. He believed that, with the right opportunities and with proper schooling, you could achieve anything.”

His nephew Bruno, who had always been close to his uncle throughout his childhood, recalled the winter of 1993 and the start of the ’94 season.

“His personal life wasn’t going great and his career wasn’t going as he wanted,” he told me. “It was tough times for him and he was trying to work it out. There were a lot of other things going on, apart from his racing, and maybe that’s why he chose not to listen to the advice his family were trying to give him. It didn’t help that they felt his girlfriend was not right for him. Remember, too, that he had serious concerns about the new technical rules for that F1 season in ’94. He felt the cars were going to be hard to drive, that there were dangers, that people would have accidents. Some people have said he was considering retirement, had begun to feel exhausted, but I don’t think that was the case. He was as ambitious as ever, as competitive as he always was. But it is true that he had begun to think about other things in his life and he was somehow a little different in 1994.”

Bianca Senna shares her uncle’s altruistic values

Getty Images

Bernie Ecclestone and Senna in conversation, Canada, ’91

The Senna family remains devoted to the institute. They feel strongly that this is what Ayrton would have wanted them to do.

“He told me he wanted to help in a more systematic way,” Viviane related, “not simply one person here, and another person there, it had to be more organised. So he asked me to plan something, some system, that would help children and adolescents to have a better future. This was two months before the race at Imola. So I began to work on a structure. We had no opportunity to talk again, but we had his wish in our hands, and the family has worked to fulfil that dream. Ayrton did not know how to help, but he wanted to do something for his people so he asked me to think about how such a scheme could be organised.

“We worked quickly. He had spoken to me in March, the accident was in May, and by July we had established the Senna Institute. It was hard, we had to do everything ourselves, find the people and places where help was needed most. Ayrton believed in God and this belief was part of him as a person and a part of his relationships with other people. The biggest reason that he was in this frame of mind in 1994 was that he wanted to help, make use of his passion for his country and his connections with his country. Senna not only flew the Brazilian flag from the car after winning a race, he flew it wherever he went, a crusader for those less fortunate than him.”

His niece Bianca continues to fly the flag. “I believe he would feel very fulfilled to see all the great work that Viviane started 30 years ago and is still advocating today,” Bianca says. “Our family has foregone over $500m in licensing and image rights, instead directing these resources to support the initiatives of the Senna Institute. We have turned a tragedy into an opportunity to impact the lives of millions, to help them realise their full potential.

Smiles at an institute fundraiser.

“The Brazilian education system remains in a state of sub-par quality. Only 10 out of every 100 children have successfully completed high school and this scenario was exacerbated by the prolonged period during which students were out of school due to the Covid pandemic. We believe the best way to change this is by providing the tools, and the teachers, to develop each child’s potential. These are the values of Ayrton and his legacy.”

Bernie Ecclestone, with his Brazilian wife Fabiana, owns a home and a coffee farm just a helicopter hop from São Paulo and has advised the Ayrton Senna Institute. Bernie played his part, too, in persuading the local government to upgrade Interlagos when moves were afoot to shift the Brazilian Grand Prix to Rio de Janeiro. He has good reason to respect South American drivers having employed Carlos Reutemann, Carlos Pace and Nelson Piquet.

“I first met Senna when he was in Formula 3,” Ecclestone told me on a visit to Goodwood. “I was interested, he was going well, and we gave him a run in a Brabham in 1983. He seemed like a good person, incredibly self-confident. We offered him a drive for ’84, it didn’t happen, but his potential was obvious. He was one of the best I’ve seen, extremely focused. Maybe he could have done even more than Michael Schumacher had he lived. He will always be remembered – just look around, his fans will always be there, not just because he was a great racing driver, he was a good person, what he did for children in Brazil.”

With nephew Bruno Senna, Interlagos, 1993.

Mexican Jo Ramirez, team manager at McLaren, was Senna’s confidant and very close to Ayrton during his battles with team-mate Alain Prost. They had talked about the problems facing children in São Paulo.

“He loved children so much, and they loved him,” remembers Jo, “and he spoke to me often about how much he wanted to help them. He came from a privileged background but he was always aware that so many Brazilian children had no real chance in life, and through no fault of their own. He never refused an autograph or a photo with children. He had this great love for the new generation, and he was very fond of Bruno, almost like a child of his own. He was more proud of being a Brazilian towards the end of his life, and he always made a point of carrying the flag, wherever we were in the world. He would be pleased to know what the institute has achieved. I always felt he might have become the minister of sport in Brazil, or might even have run for president.

“He was so methodical and he had this really frightening will to win, whatever it took. By the end of 1993 he was overdoing it. He had too many commercial things going on. You name it, he was putting his name to it. Michael Schumacher and Benetton were pushing him hard as well, and it was just becoming too much. I’m not saying this had anything to do with the accident but, being close to him, I knew he was under a lot of pressure.”

Another man who appreciated the legacy of Senna is Pat Symonds who was at Toleman when the Brazilian used the team as his stepping stone into Formula 1. “He was a deep thinker, a religious man, a man of decent morals,” Symonds told me, “and coming from a wealthy family he saw the appalling divisions in Brazilian society. I’m not a bit surprised that later in his life he wanted to be charitable, to put something back into his own country. In 1994, after the tragedy of Imola, Frank Williams observed that, as great a driver as Senna undoubtedly was, he was ultimately an even greater man outside the car than he was inside it.”

“He realised that the new FW16 wasn’t yet fully competitive”

“For me, it was special to have such a hero from inside my family,” Bruno told me, “and even when we raced karts together he was competitive. Ayrton was not a fragile person, but he had a very open side to him, very naive sometimes, and motor racing has never been a sport for naive people. So he hardened himself for racing. But there were many moments when you could see his softer side coming out. For example when there were accidents, he wanted to help, wanted to know why it happened. For those who didn’t know him well, it was hard to see that side of Ayrton, but he was a kind person and totally normal, much softer, when he was away from his motor racing.”

Going back to that winter of 1993/94 Bruno remembers Ayrton being in some way troubled.

Toleman days, 1984 – Pat Symonds saw a thoughtful man in Senna

Getty Images

“The only other time I saw him like this was in 1989 at Suzuka, in the war with Prost – he was very low at that point. He was worrying about a lot of things, about his businesses, and he was always on the phone. I think he foresaw some of the problems that would come in 1994 and he was not yet happy with the Williams, thinking he might not be in a position to win. He took more risks than the other drivers and he realised that the new FW16 wasn’t yet fully competitive. I know 1993 had been tough for him and he was mentally drained. He was a bit less smiley, a bit more uptight. There were too many things going on for him and that’s when he spoke to my mother about getting the institute organised. He had so much good in his life, he wanted to give something back. He would be proud of what Bianca and Viviane have achieved.”

Over the last three decades the Ayrton Senna Institute has reached more than 36 million children and trained more than 300,000 teachers. Bianca, who was 14 when her uncle died, says the work will continue.

“We are steadfast in our conviction that his belief in the transformative power of focusing on children and their education would contribute not only to the success of individuals but also our nation. This is what he would have wanted and his legacy has inspired us all to continue the work of the institute that Viviane set up 30 years ago.”

Bruno tribute to his uncle before the 2019 Brazilian GP

Getty Images