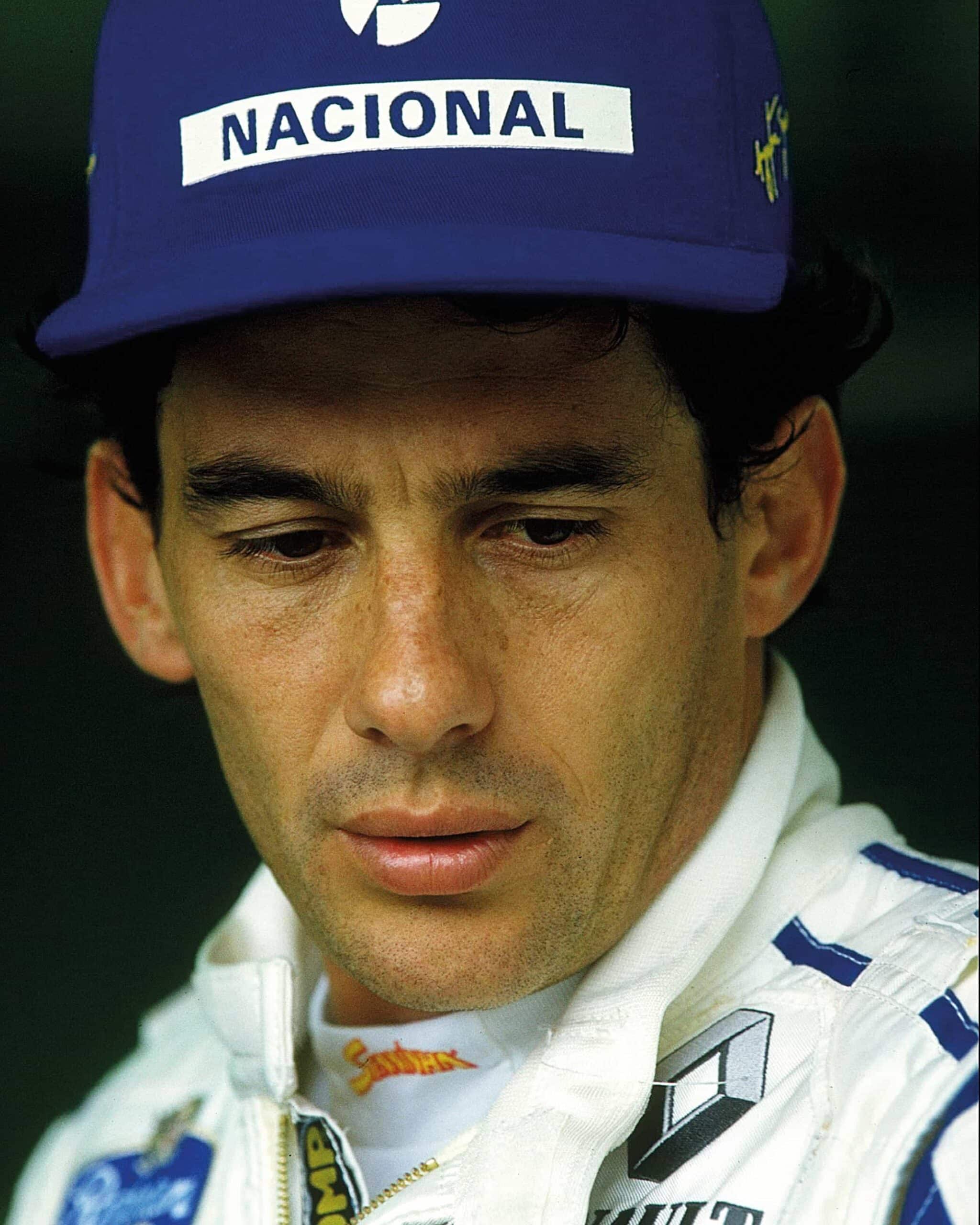

Ayrton Senna, 30 years on from Imola

Thirty years after the death of Ayrton Senna, David Tremayne recounts the dark events of the 1994 San Marino Grand Prix and explains why the Brazilian’s legendary status will live forever

Getty Images / DPPI

The death of Ayrton Senna was as massive a blow to racing as Jim Clark’s in 1968. Both were the clear yardsticks of their generation, though Ayrton’s occasional penchant for reckless aggression perhaps put him at greater risk. Both had artistic flair and such innate God-given talent that one always believed it would ultimately be their protective talisman. They were simply too good to die in racing cars.

Thirty years ago this month what made Ayrton’s death so stunning and brutal was that by 1994 we all thought racing had come so far in terms of safety, that so many of the old spectres – even fire, the drivers’ greatest fear – had so successfully been exorcised. Formula 1 had reached the stage where people had almost allowed themselves to believe that death was no longer a visitor to the races.

How wrong we were. And how horribly that was proven as, in images that still haunt the sport to this day, he became arguably the first F1 fatality on live television.

I loved Imola, and the little hotel in Fontanelice – La Pergola – that was run by a chirpy Italian lady called Rosa, whose husband Leo would glare at us from the kitchen, as he watched her embracing us upon arrival.

We were all excited to see what aerodynamic magic Adrian Newey had woven to pull Williams back on par with Benetton, and what sort of dent Ayrton could make in the 20-point lead upstart Michael Schumacher had opened up in the first two rounds after the great champion had failed to finish either the Brazilian or Pacific GPs.

“People had allowed themselves to believe that death was no longer a visitor to the races”

The bad things started happening 16 minutes into Friday afternoon’s qualifying session when Rubens Barrichello had his massive accident when he lost control of his Jordan 194 in the Variante Bassa after putting a wheel over a kerb. The car was thrown brutally into the debris fence at around 140mph and came to a halt almost immediately in one of those really horrible shunts where the energy is absorbed so abruptly. We regarded it as a miraculous deliverance that the likeable little Brazilian escaped with nothing worse than a broken nose.

The following afternoon I was watching qualifying on television with my journalist friend Joe Saward when Roland Ratzenberger crashed on the run down to Tosa, 20 minutes into the session. Roland was a friend whom I hadn’t seen for several years, since our F3 days in 1987. We hadn’t been able to catch-up in TI Aida, and as I’d been walking through the paddock in Imola on Thursday afternoon he had grabbed my arm, and there we were, hugging and laughing, both so happy he had finally realised his dream to drive in F1. He was a lovely, friendly, happy guy, and we agreed to have dinner with some mutual friends on Saturday night.

But as Joe and I watched the amethyst Simtek come slithering to a halt after what had clearly been a very heavy impact, and Joe said, very quietly, “Look at his head,” we realised the worst. Four years earlier, witnessing Martin Donnelly’s horrible shunt right in front of me in Jerez, I had believed I had just seen my first mate being killed in a racing car. Thankfully Martin survived. Sadly, Roland did not.

He was the first man to die in an F1 car since Elio de Angelis in that scandalous accident testing at Paul Ricard in 1986, and his death hit very hard. Everyone was understandably subdued on Sunday morning, and there were suggestions going round that Ayrton had been particularly upset and was even being counselled by Professor Sid Watkins not to race. But of course he did, because that was how he was made, and it transpired that he carried an Austrian flag that he intended to wave in victory. For all his outward aggression at the wheel, I think that said as much about the inner Ayrton as anything could, just as had his determination to visit the Donnelly crash scene. He did it because, as an elder statesman, he needed to know what to do in such circumstances. And as a driver he needed to know how it felt to peer into the black pit when things went wrong, and not just what victory champagne tasted like.

Contemplation for Ayrton Senna on the grid at Imola – with an Austrian flag hidden in the car to honour Roland Ratzenberger

Things were unusually tense prior to the start, and not just because of the events of Friday and Saturday. There was new concern when JJ Lehto stalled his Benetton, in fifth place on the left-hand side of the grid. He was having his first race after sustaining a neck injury earlier in the year, and this was his big chance. I remember praying nobody would hit him, but Pedro Lamy was unsighted and his Lotus 107C smashed heavily into the back of the stricken B194, strewing debris everywhere. As if things weren’t already bad enough for JJ, he and Evan Demoulas had driven down from Monaco with Roland. Now we watched in horror as a wheel was hurled right over the grandstand to the left of the grid, though it would be a very long time before it was revealed that it had struck a policeman.

“I still believe Ayrton’s the most intelligent, deep-thinking and charismatic driver I’ve met”

There followed that lengthy delay as the grid was cleaned, and the field ran at very low speed behind the disgracefully slow Opel Vectra safety car. Tyre pressures dropped, and ride heights with them… Then the man at the end of the pitlane incomprehensibly let Érik Comas rejoin in a Larrousse that had been fixed after sustaining damage in that melee at the start. He had blasted unawares into Tamburello and had to brake savagely as he encountered the aftermath of Ayrton’s accident. He stopped virtually alongside the prone body of the only man who had stopped to help him when he crashed at Spa in 1992, and it destroyed him.

It was immediately obvious to everyone that Ayrton’s plight was very serious, and it struck the sport like a thunderbolt.

As the wretched race was restarted and dragged on and on, lap after lap, Nigel Roebuck and I leaned on the windowsill in the press room and looked out over the pitlane. “This is doomed, like the bloody Indy 500 in 1973,” I said to him, and we remembered how pitman Armando Teran had been killed by a fire truck travelling the ‘wrong’ way up the pitroad to Swede Savage’s accident in Turn 4. “We’ve done 75%, why don’t they just stop this awful nonsense? All we need now is a shunt in the pitlane.” And within moments, on the 49th lap, there it was, as Michele Alboreto’s Minardi lost a wheel while rejoining, injuring mechanics Claudio Bisi, Daniele Volpi, Maurizio Barbieri and Neil Baldry. And still the race dragged on to its bitter conclusion.

Senna before the ’94 season opener in Brazil

Getty Images

We learned around 5.30pm that Ayrton had died. Some Fleet Street journalists who knew little about racing walked around in a daze, more than one actually saying, “Nobody told us this sort of thing could happen!” The hardened pros who knew their sport’s bloody history tore a page out of the Tyler Alexander notebook of survival and got on with the job, saving their emotions until they were locked away somewhere private. It was a long night.

When Nigel and I checked out on Monday morning, it was as if Rosa felt she needed to apologise on Italy’s behalf for our awful weekend. She was tearful as she handed us each a bottle of red wine in a beautifully touching gesture. She wasn’t the only one.

Press day at Motoring News was on the Tuesday that Bank Holiday week, and I remember the normally bubbly office being as silent as a morgue. Our little band of enthusiasts worked superbly, and many years later rally writer Paul Fearnley said to me, “We knew you had to write all the F1 stuff and that there wasn’t anything we could do to help with that, so we just made sure that we all did our jobs as efficiently as we could.” I knew that subconsciously, and was never more proud of what the paper stood for that wretched day, and how we covered a tragedy that affected us all so deeply, and so many millions of people across the world. If we ever did something that really mattered, I believe that was it.

Inevitably, I’ve often thought of Ayrton in the ensuing years. The sad thing in racing, as in life, is that everything immutably moves on. It’s what always angered me so much as a young fan, when somebody you cared about and whose career you followed closely – Jimmy, Pedro Rodríguez, Jo Siffert, Roger Williamson, Tony Brise, Tom Pryce – was suddenly left behind, their story done.

How do I remember him?

I still believe he’s the most intelligent, deep-thinking and charismatic driver I’ve ever met, and that beneath his sometimes brittle yet impervious outer shell there was an immensely kind, sensitive and generous character that was quite at odds with the monster he could be on the track when the dark mood was upon him.

Another crash – Benetton’s JJ Lehto and Lotus’s Pedro Lamy collide at the start of the San Marino GP.

Getty Images

If he was sore about something critical you’d written – as I did whenever he bullied somebody off the track – his eyes could freeze your heart. But he had a fundamentally kind face and smile. I remember too, that sing-song voice and those round-the-table group conversations outside the McLaren motorhome. Sometimes we’d get him going on something really good and he would dig deep to give us carefully worded insights, and then usually one charming older guy would ruin it all unintentionally with a well-meant but crass interruption, such as, “I say, old boy, do you really think you can beat Alain tomorrow?” and Ayrton would sigh and shut down, as if to say, “Right, that’s your lot.”

I will forever remember him one afternoon in his hotel room in Adelaide. The very fact that a driver would entertain a few reptiles in his private chambers like that was remarkable in itself, and that interview was the most mesmerising I have ever been a part of.

It happened two weeks after That Shunt at Suzuka in 1990 when he deliberately took Alain off after losing out to him at the start. This was long before you could doctor photos, but when showed photographic evidence he point-blank refused to accept that he drove into the Ferrari and took off its rear wing, claiming it had fallen off of its own accord.

He was implacable, yet a year later in an ill-tempered press conference in Suzuka after handing victory to team-mate Gerhard Berger, he admitted freely that he had done it on purpose. That, having been cheated of pole on the clean side of the grid by the dread Balestre, he had decided: “If that guy gets to the first corner ahead, he’s not gonna make it.” It was a fascinating insight into the self-belief he needed every step of the way, even when he knew it defied truth.

That was the dark side of the man of whom Alain had said in Portugal in 1988 after that swerve at his car down the pitstraight, “If he wants it so much he is prepared to die for it,” meaning the world championship, “then he’s welcome to it.” But that day Down Under there were other comments.

I always believed that he had deliberately ventured to the black pit that day in Jerez after Donnelly’s crash, and boldly faced the messages it relayed to him as a fellow racer lay close to death. And that when qualifying resumed there, and he set the 50th pole of his career, he had simply gone out determined to teach the track that mere Tarmac and gravel could never quell the racing driver’s spirit.

I remember the powerful expletive he used in the post-run conference to describe what Nelson Piquet and Olivier Grouillard were doing as he came upon them while running at maximum commitment, so soon after such an accident. His anger and utter disdain.

Now I wanted to know why he went to the accident scene, and he went into that intensity zone again and we all strained to hear an answer that – I later timed it – took 37 seconds for him to formulate. He wasn’t crying, but his eyes were full with emotion. You could have heard a shadow move.

“One thinks of the loss of opportunities, and of the great things he would have achieved”

“For myself,” the answer eventually came. And how chilling it sounds today in light of what would eventually befall him as he added, “I did it because anything like that can happen to any of us. I knew it was something bad, but I wanted to see for myself. Afterwards, I didn’t know how fast I could go. Or how slow.”

He took another long pause, and I asked did he have to be brave to do that? A third pause. “As a racing driver there are some things you have to go through, to cope with,” he said softly. “Sometimes they are not human, yet you go through it and do them just because of the feelings that you get by driving, that you don’t get in another profession. Some of the things are not pleasant, but in order to have some of the nice things, you have to face them.”

I’ve always most respected people in situations in which, as Nigel Roebuck terms it, they are abnormally brave. And if I’m ever asked what I remember best about Ayrton, it was what he did that day, the honour and courage with which he conducted himself when that session resumed. For me, that was his finest moment as a racer and as a man.

I also remember, when he rescued Érik at Spa that time, he had been delighted when Prof told him he had done exactly what he had counselled him to do in such circumstances.

But what paradoxes, that the man who could run rival Prost off the road rather than surrender a corner to him, could care so much about fellow drivers in different circumstances.

After the re-start following the Lehto and Lamy incident, Senna was leading Schumacher –before disaster struck

All the good guys push hard, of course. It’s the nature of the game. But in my mind’s eye I still see Ayrton pushing so hard on his final qualifying laps, still remember the tension and excitement that always presaged that last effort, especially if somebody else had gone quicker. You literally held your breath while he was at work, especially at somewhere like Monaco where the lack of a safety net was so brutally evident. To watch him at such moments was to be awed by his commitment.

I don’t regret much in my life, but in reflective moments I wish I’d been mature enough or less judgemental, to have suggested we have dinner together, bury a hatchet or two and talk about things such as life.

At the time of his death the blow was the loss of such a charismatic star, the cruelty and effrontery that one of his stellar talent, just like Jimmy, should be left behind. Now, as inevitably we have had to adjust, one thinks of the loss of such opportunities, and of the great things he would have gone on to achieve for his countrymen when he stopped racing.

Of all the champions I’ve known he was probably the fastest, most cerebral, vocal and aggressive, while out of the cockpit he could be a gentle character who thought so much about other people.

He remains relevant today because many young drivers now making their names were influenced by him, or their mentoring parents’ respect for him, at crucial stages of their own careers. And then there is the Senna Foundation, on which he had been working when he was killed. An NGO recognised by UNESCO for its work in education and now run by his sister Viviane and her daughter Bianca. So far it has helped more than 35 million children.

SENNA! The name resonates and inspires, the charisma endures. And his is surely the greatest legacy of any motor racing star.