The Jaguar F1 horror that still haunts Ford

The Blue Oval is plotting its Formula 1 return with Red Bull. But as Maurice Hamilton explains, Ford’s last effort in green offers a red-light warning of how it can all go wrong

Grand Prix Photo

Ford and Red Bull in alliance for 2026? These two have previous, and it didn’t end well. OK, the colours, brand names and personalities were different when Jaguar Racing was launched at the turn of the millennium. But as it prepares to dive back into the Formula 1 cauldron Ford will be all too aware that the waking nightmare from last time cannot – and must not – be repeated.

Just two podiums to show after five indifferent seasons meant Jaguar gained nothing but notoriety from its only chapter in grand prix racing, by becoming one of the most high-profile failures in F1. The British-based team would also have been listed as the most profligate (a distinction falling to Toyota) were it not for parent company Ford reducing a healthy budget that had been squandered early on. This failure to understand F1’s unique needs was one of two major handicaps blighting the much-vaunted programme, the other being a revolving door of management that made Jaguar Racing look like an employment bureau rather than a slick F1 team.

‘The Cat is Back’: Johnny Herbert in the Jaguar R1 at the 2000 season opener Australian Grand Prix. His race lasted a lap

The paradox was that Ford’s initial F1 investment in Stewart Grand Prix in 1996 had been as sound as the workmanlike little team which the astute Jackie Stewart then sold to Ford three years later. Even more ironic, Stewart’s second place at Monaco and victory at the Nürburgring within 31 months of conception had led the Ford hierarchy to assume this grand prix business had to be easier than shifting motor cars in showrooms around the world. It seemed to the top level of Ford Motor Company management in Michigan that Stewart and his son, Paul, had done all the donkey work and the Blue Oval was set to join Ferrari’s Prancing Horse and the Mercedes Three-Pointed Star as symbols of competitive global greatness.

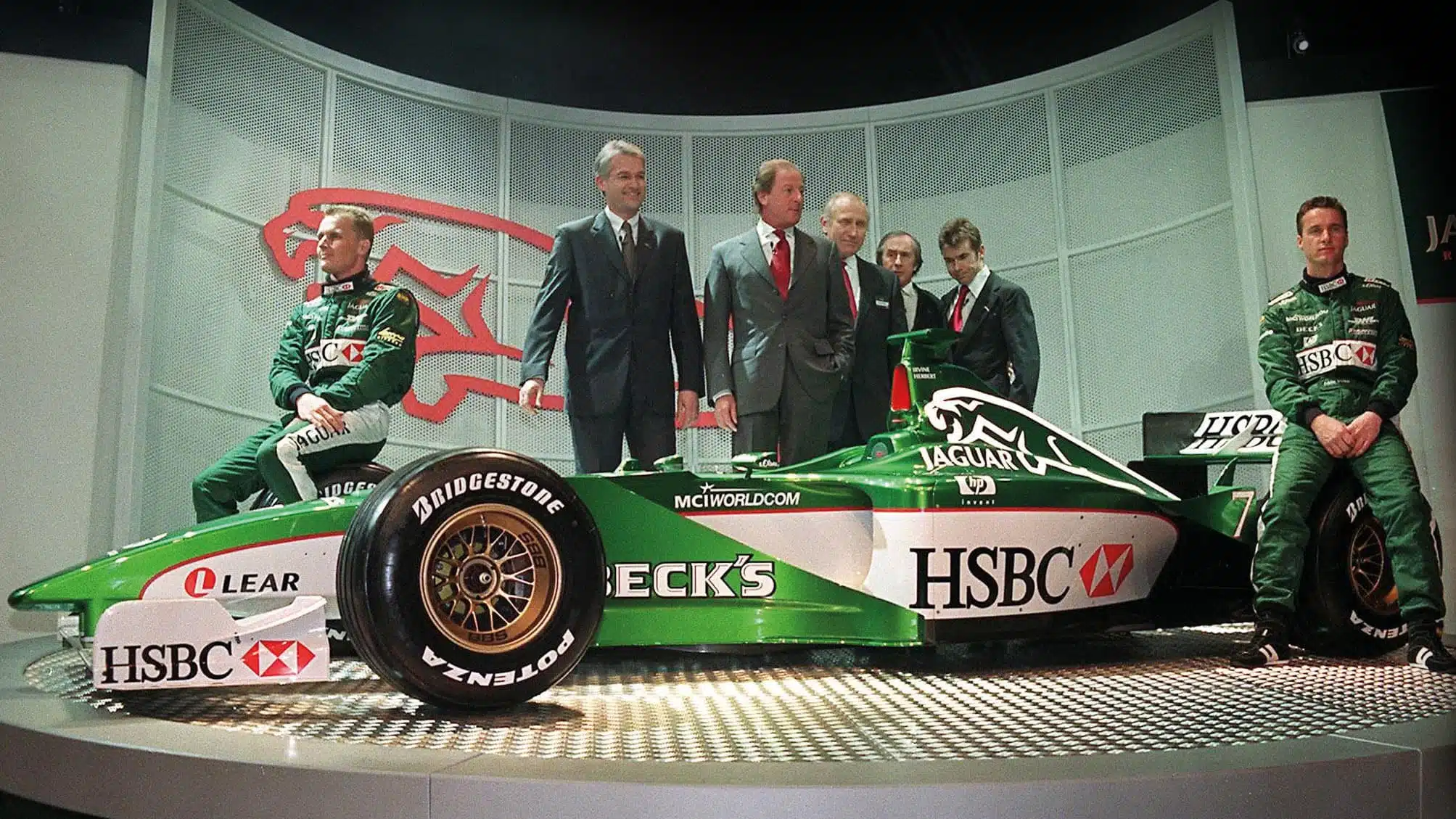

The fundamental failing of such a bold belief was painfully apparent at the scene of Jaguar Racing’s official launch in London on the evening of Tuesday, January 25, 2000. Ford chose Lord’s, the so-called Home of Cricket, to mark the return of a famous motor racing name. But the accompanying speeches would have the same effect on Jaguar’s projected overambition as the entire team being bowled leg before wicket with successive balls.

Herbert retired from the French GP with gearbox issues

Wolfgang Reitzle stepped up to the crease and clearly thought he was hitting a six by speaking with intense enthusiasm about winning races in 2000 and the championship two years later. As recently appointed boss of the F1 effort, the head of Ford’s Premier Automotive Group appeared to believe that Jaguar Racing was simply another high-end marque to join his recently acquired roster of Lincoln, Mercury, Aston Martin and others. This great name would supposedly carry on where Jaguar’s competition department had left off in the 1950s. Black and white footage of glory days at Le Mans was used to support a self-indulgent slogan, ‘The Cat is Back’. It was as misplaced as Audi, should they be so naive, choosing to talk about grand prix victories for Auto Union in the 1930s as the driving force behind their recent decision to go Formula 1 racing in 2026.

Irvine took the R2 to its sole podium in 2001 – Monaco

Getty Images

Jaguar’s unintentional denigration was magnified at the first race of 2000 when Ferrari’s emblem was carried overhead on a gleaming Qantas Boeing 747 and ‘The Cat is Back’ appeared on a Melbourne tram, this unfortunate symbol in dark green clanking slowly through the city’s streets. The Jaguar R1 race cars, of a similar colour, weren’t much better. Following the Lord’s launch of inflated ideas, the F1 paddock was fertile ground for silly jokes about Jaguars with walnut dashboards and leather upholstery, particularly when the first race ended with clutch trouble for Johnny Herbert on the opening lap and Eddie Irvine spinning off not long after to avoid someone else’s accident.

“There were jokes about Jaguars with x dashboards”

The compact Stewart Grand Prix team remained at the core, but Jaguar Racing was already being seen as top heavy and increasingly bureaucratic. Neil Ressler, a quietly avuncular man, had been responsible for Ford’s Advanced Vehicle Technology and an advocate for the motor giant backing Stewart Grand Prix in 1996. Now he was chairman and CEO of Jaguar Racing (Jackie Stewart, perhaps having sensed what was coming, had declined the position, but remained on the board). As the 2000 season wore on, Ressler found himself presiding over a team that had been on the up but was now standing still.

The shackled potential was not lost on Gary Anderson as the experienced F1 engineer continued the role of technical director held at SGP. Very much a hands-on operator, Anderson was increasingly frustrated by Ford’s doctrine of ‘Do it our way, or not at all’, even though the company dogma usually had as much relevance to F1 as a Fiesta boot liner to a bargeboard.

Herbert’s team-mate in 2000 was Eddie Irvine, here picking up rare points at Monaco

Getty Images

Niki Lauda was keen to point out that Bobby Rahal, left, was in charge.

Grand Prix Photo

Jaguar Racing chairman and CEO Neil Ressler presided over a stalled team

DPPI

There were, however, self-inflicted complications such as a combined gearbox and (Cosworth) engine oil pump system, plus the need to use a wind tunnel 6000 miles away in California. But that did not stop a growing number of critics from espousing their pet theories.

“Herbert ended his tenure with Jaguar on the worst possible note – a massive accident”

Under the heading Jaguar going nowhere fast, The Sunday Times on June 23, 2000, kicked off a withering evaluation with the sub-heading: “Many mistakes have been made, but signing Eddie Irvine was probably the biggest.” For all of Irvine’s irritating insouciance and a reported fee of $15m, it was an unfortunate observation since, two weeks before, the Ulsterman had given Jaguar their first points of the season with a hard-won fourth place at Monaco.

That would turn out to be the highlight of 2000, Jaguar claiming just one more point with sixth in Malaysia, the final of the season’s 17 grands prix. At the same race, Herbert had ended his tenure with Jaguar on the worst possible note at Sepang when a rear suspension failure caused a massive accident from which he was extremely fortunate to escape unharmed.

Herbert at Interlagos, 2000 – another DNF

Getty Images

‘Escape’ might also have been an appropriate term when describing the departure of Anderson, to be replaced by Steve Nichols. The former McLaren designer took a noticeably understated role at the Jaguar R2 launch which, in itself, was subdued compared to the misguided hype at Lord’s 12 months before. Ressler had been forced to return to the USA for family reasons while, coming in the opposite direction, the appointment of Bobby Rahal brought a racer and IndyCar team owner with what was hoped to be a better understanding of the task ahead. Nonetheless, for all his strong talk (“I wasn’t a wanker driver; I’m not going to be a wanker boss”), the Indy 500 winner had to accept the Jaguar R2 and its latest Cosworth V10 as fait accompli and, all being well, less prone to mechanical failure than its predecessor.

R2 would indeed turn out to be more reliable. But it was also slow. Jaguar would finish two from the bottom of the constructors’ table, almost half the points coming from third place for Irvine at Monaco. Luciano Burti scored no points during his brief tenure as Herbert’s replacement, Pedro de la Rosa taking over to claim two minor places.

No surprise, then, that Jaguar would create more headlines off the track than on it – particularly when Reitzle brought Niki Lauda on board to act as the link between Jaguar Racing, Cosworth and PI Group (the electronics provider, also owned by Ford). Despite Lauda going out of his way to emphasise that Rahal was running the racing team, it was soon clear that the three-time world champion had his pragmatic shovel under the American. By August, he was gone, Rahal’s departure no doubt hastened by his friend, Adrian Newey, reneging on a firm agreement to leave McLaren and become Jaguar’s technical chief.

Wolfgang Reitzle was head of Jaguar’s F1 programme.

Getty Images

Guenther Steiner came in as MD in 2001

Getty Images

Irvine knew the R3 was poor

Getty Images

The turmoil continued when Nichols headed for the door and Guenther Steiner (former design chief with the Ford Focus rally programme) was appointed managing director. As with his predecessor, Steiner knew the specification for the car under his charge had long since been finalised. The launch of R3 had an even lower profile than that of R2, Lauda setting the tone when he turned up in blue jeans, deck shoes, jacket, sweater and the familiar red Parmalat hat. Predictions for the coming season were in short supply. Which was just as well.

Towards the end of the third week in January 2002, I was covering the Monte Carlo Rally when my phone rang. It was Eddie Irvine. Calls from Irvine were rare and usually free of small talk. The deadpan opening to this one was no exception: “Don’t put any money on this car. It’s shit.”

Irvine’s eviscerating summary was based on his first run during a test at Barcelona, his instincts telling him something was fundamentally wrong with R3. He suspected the front suspension was flexing. It would turn out to be worse than that; the rigidity of the entire chassis had been compromised by a large hole cut in the front to improve access.

Irvine with Jaguar’s technical director Steve Nichols in pre-season testing, Barcelona, 2002 – It was here that Irvine formed his strong opinion of the R3

Getty Images

R3 suffered from chassis-flex issues

Getty Images

Rapid revisions were carried out; too late to save the 2002 season. Lauda’s post-season analysis was typically succinct. “The car was designed all wrong. It didn’t work.” Nonetheless, R3 had been reasonable on low downforce tracks, as proved by sixth at Spa and third at Monza, but not enough to elevate Jaguar from the single-figure brigade at the bottom of the championship. Despite scoring all eight points, Irvine was the fall guy. And so, too, was his boss.

On November 26, 2002, under the heading A famous marque in the last-chance saloon, The Guardian reported that Lauda had been sacked, his place taken by Richard Parry-Jones. Having arrived on the scene earlier in the year, Ford’s chief technical officer had brought with him Tony Purnell and David Pitchforth, neither of whom had impressed Lauda. “We had a very good race team in the end,” reflected Lauda. “The people in charge, put there by Ford, were not so good. They didn’t know anything about racing. I had underestimated the British way of working together. These guys [Purnell and Pitchforth; engineers who had worked through the Ford system] convinced Parry-Jones that they could run the team. I was then told they [Ford] were ending my contract early. OK, so pay me for what’s left. They didn’t want to do that but, with the help of Bernie’s [Ecclestone] lawyer, they paid. Budget had always been a problem with these people at Ford.”

“Ford’s president had visions of a sea of green at racetracks”

That wasn’t strictly true. Funding in the first year (prior to Lauda’s arrival) had been more readily available thanks to the arguably misguided enthusiasm of Jacques Nasser. Ford’s president had visited the 1999 Hungarian Grand Prix where, bowled over by the number of passionate Ferrari supporters in red, Nasser had eager visions of Jaguar and its racing heritage inspiring a sea of green at racetracks around the world.

“It was typical of Ford’s thinking,” recalled Irvine. “The F1 team was a great idea – but badly executed. They paid way too much for Stewart [Grand Prix]. When I was [later] dealing in property in Miami, I remember this deal for two houses went through and I thought: “Jeez! Who paid that for that?” It was Jacques Nasser. He paid nearly double what the houses were worth – and that tells you a lot about how he ran Ford and Jaguar.”

The same Milton Keynes base Red Bull uses today (but expanded)

Grand Prix photo

Burning money

Mark Webber was Irvine’s replacement for 2003

Getty Images

When Nasser retired at the end of 2001, William Clay Ford Jr did not share his presidential predecessor’s interest in F1. Questions were asked about expenditure on a team that did not carry Ford branding and, more directly: “This guy Ed Irvine. Who’s he – apart from being the second highest on our payroll?” The funding for Jaguar Racing was reduced for 2003, which was unfortunate timing for Mark Webber who’d joined from Minardi as Irvine’s replacement.

Initially, Webber was savouring the elevation following his debut F1 season. Come the British Grand Prix, he had scored points (awarded down to eighth place) six times and was enjoying a productive working relationship with the latest technical director, Mark Gillan (Irvine: “Mark was one of the best. I loved working with him”). Gillan had arrived from McLaren in 2002 in time to profit from Ford’s belated acceptance that a wind tunnel in England would be infinitely better than one in California. But inconsistencies continued. Jaguar was to remain at the bottom of the table, a handful of points ahead of Toyota and Jordan.

Jackie Stewart and Richard Parry-Jones at a media briefing announcing Lauda’s departure

Getty Images

Ford put the brakes on at the end of 2004

Grand prix Photo

Christian Klien hits the barrier at Monaco in 2004

Grand Prix photo

On the evening of Friday, December 12, 2003, a few members of the F1 media were invited to dinner at 1 Lombard Street, an upmarket restaurant in the heart of London’s City. It was a strange affair, mainly notable for Purnell explaining why the promising and popular British driver Justin Wilson (signed to replace Antônio Pizzonia halfway through 2003) had been dropped in favour of Christian Klien based on a mere handful of test laps by the Austrian. It was no coincidence that Klien was also bringing several million much-needed dollars from his sponsor, Red Bull. This would turn out to be another irony – among many.

During Lauda’s time with Jaguar, he had introduced Parry-Jones to the relatively unknown Dietrich Mateschitz, saying the boss of Red Bull had an eye on expansion into the American market and was very interested in either sponsoring the Jaguar team in a big way or, perhaps, investing in half of it. Ford flatly rejected the offer. “Completely f***ing crazy,” said Lauda. “These people would rather close down the team than have an energy drink on their car. This said everything about Ford and F1.”

On November 15, after five finishes in the points and a best of two sixth places from 36 starts in 2004, Jaguar Racing was sold for a token amount to Mateschitz. Six years later Red Bull Racing, operating out of the same premises in Milton Keynes, would win the first of four successive drivers’ and constructors’ championships. Newey had joined in 2006. Significantly, the same team principal, chief technical director, chief engineering officer and sporting director remain in place today – probably because there has been no interference from a misguided monolith some 4000 miles and another world away.

Jaguar mechanics at the team’s final grand prix – Brazil, 2004

Getty Images