Goodwood’s great races: best of the ‘50s and ‘60s

Goodwood hosted its first race 75 years ago and ushered in an era of incredible action before going into hibernation in 1966. Here Paul Fearnley nominates the pick of those early races which defined the circuit

Behind the wheel, from left: Alan Brown, Eric Brandon, Juan Manuel Fangio and Mike Hawthorn at Goodwood, 1952

Getty Images

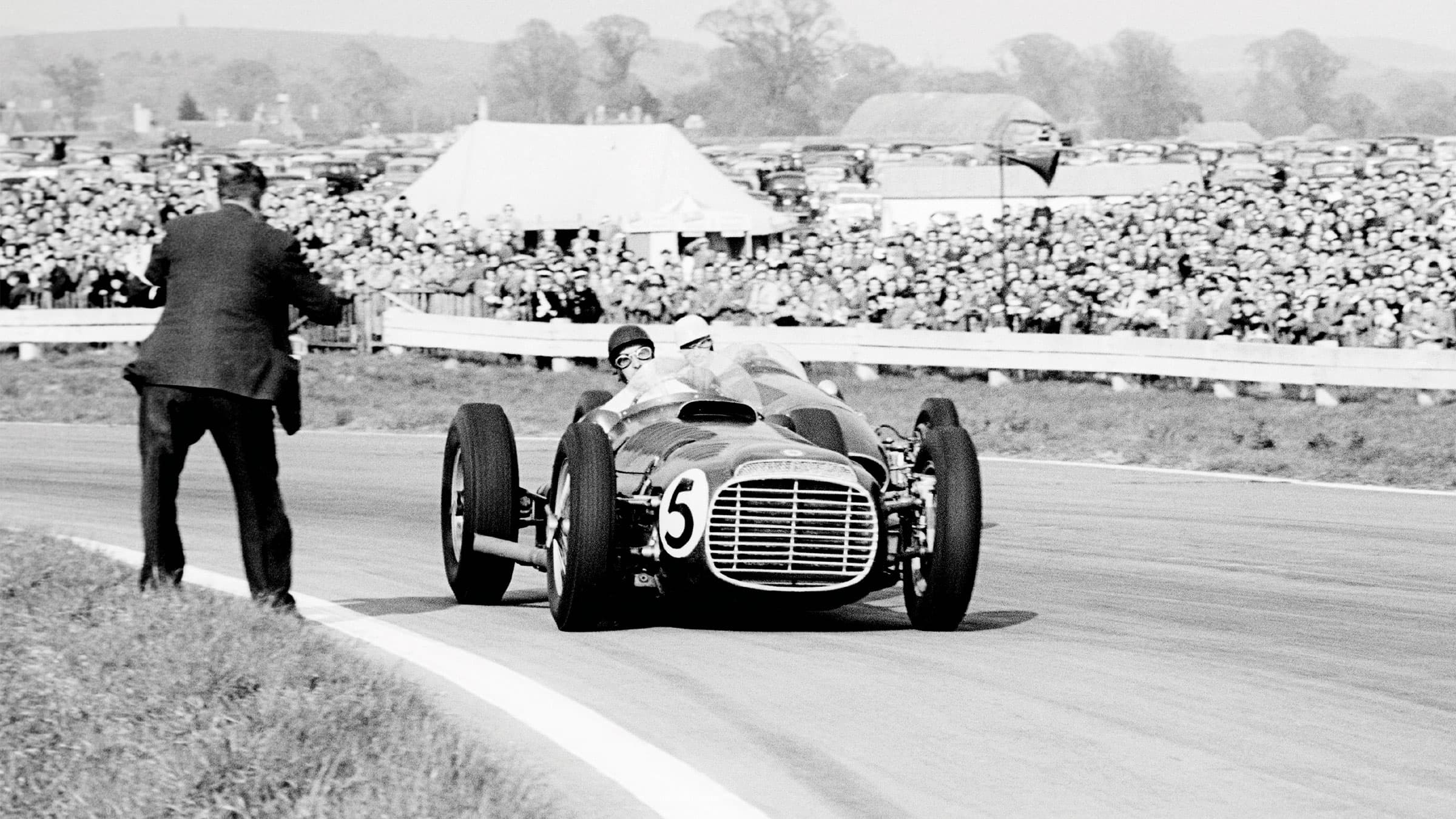

1952 Lavant Cup

April 14

Reigning Formula 1 world champion Juan Manuel Fangio was coming to Goodwood – as was his good mate José Froilán González, thrilling winner for Ferrari of the previous year’s British Grand Prix at Silverstone. That a young man from Farnham, Surrey was about to race against these Argentine supermen in the third Cooper-Bristol built was but a footnote. Yet he and it would steal the headlines.

Mike Hawthorn’s impressive performances at Goodwood and elsewhere during 1951 in pre-war Riley sports cars fastidiously tuned by his father had piqued the interest of aficionados – John Cooper, for instance, was happy to have him drive one of his new Formula 2 single-seaters – but what happened next came as a complete surprise to everyone.

Having grabbed but a half hour’s kip after working through the night cutting new valve-seats, it dawned on Hawthorn that his brief test of an unfamiliar car had eschewed a standing start. So he held its throttle steady rather than blip it and trusted to luck – plus a slug of nitromethane! He won this F2 six-lapper by 21sec, ahead of the first and second Cooper-Bristols built.

Better was to come on this day – he beat Fangio’s (misfiring) sister car in scoring a second victory, and chased the much more powerful Ferrari of González to finish runner-up in the meeting’s big race – the Richmond Trophy. Hawthorn’s star quality had by then been established.

1952 News of the World International Nine Hours

August 16

A drying track enabled Jaguar’s C-types to assert dominance over Aston Martin’s nimbler but less powerful DB3s as dusk descended. By 9pm they were five laps up and Goodwood’s ancestral owner invited Jaguar boss William Lyons back to the house to toast his company’s impending success. At which point the Leaping Cat fell on its face: the second-placed car broke a half-shaft and, an hour later, the leader had to stop to repair a broken radius arm.

The racing gods continued to smile on Astons when the jacks raising the threatening Ferrari 225 S of Roy Salvadori/Bobby Baird sank into Tarmac that had melted in a pit fire that had forced a DB3’s retirement (a developing theme). Further delayed by a flat battery, ‘Salvo’ rejoined in a funk, spun at Madgwick and stalled. He restarted thanks to an illegal push-start that cost a one-lap penalty. It was Aston Martin’s night.

History repeated itself the following year when the same Jaguar pairings – Stirling Moss/Peter Walker (conrod) and Tony Rolt/Duncan Hamilton (oil pressure) – retired in the final hour. Only this time Astons scored a 1-2. By then, however, the novelty of racing until midnight – i.e. after last orders in the beer tent – had worn off.

1954 Richmond Trophy

April 19

Roy Salvadori had been denied victory twice earlier in the day by less than a second apiece. Now, in the 21-lap Formule Libre main event, he found himself bottled behind a car spraying oil and being driven very elbows-out by Ken Wharton, leading. Frustration increased until a lunge on the penultimate lap caused contact at Lavant. Both cars spun and restarted – only for Salvadori’s Maserati 250F to obliterate its clutch.

The bashed BRM V16 – deemed a write-off by the team – made it home and Wharton’s face was thunderous as he wiped hot oil from his arms. He had no intention of talking to Salvadori and vice versa – the track’s famed party atmosphere paling before two tough competitors. Salvadori’s Gilby Engineering team protested the victory – hardly the done thing – not because of the collision but because BRM had swapped drivers Wharton and Ron Flockhart between cars. The result stood.

The Duke of Richmond & Gordon, a racer at heart, sent Salvadori an engraved silver cigarette case to thank him for “the splendid show”. Ever the sophisticated operator, he sent one to Wharton, too. The verdict that mattered: racing accident.

1958 Lavant Cup

April 7

Though chalk and cheese in personality – one garrulous, the other verging on monastic – Graham Hill and Jack Brabham were peas in a pod when it came to motor racing. They pretty much invented tailored set-ups and each then applied them with a grim determination – one bristling, the other hunched – to succeed.

At this particular stage of their careers Brabham had yet to score a point in Formula 1 (fourth at the Monaco Grand Prix a few weeks later would remedy this) and Hill had yet to start a world championship grand prix (which also came at Monaco). They attacked this Formula 2 encounter as though their lives depended on it.

Brabham’s Cooper led – the Coventry Climax four-pot at the Aussie’s shoulder benefiting from an extra 15cc over that in the nose of his rival’s Lotus – but Hill drafted past down the Lavant Straight on lap 10. The response when it came was dramatic, Brabham gathering it up after using all of the road in passing around the outside at Woodcote on the penultimate lap. His winning margin – after another crossed-up exit of the Chicane – was 0.4sec. (Stuart Lewis-Evans, finished fourth.)

Much of motor racing’s ‘British’ future – including five F1 drivers’ world titles between this pair and six constructors’ between these teams (plus a couple for the Brabham marque) during the next dozen years – had been distilled in 15 hectic laps.

1959 RAC Tourist Trophy

September 5

The leader’s first pitstop had gone to careful plan: 30sec for fuel and four tyres thanks to onboard air-jacks and a 50-gallon drum atop a 20ft tower. The second stop, however, went all-to-cock: opened in error in haste, petrol gushed, to be ignited by a backfire. Roy Salvadori leapt from the cockpit via the bonnet and into the arms, coat and hat of a quick-thinking St John Ambulance volunteer. Other rescue efforts went awry, however, said tower crashing to earth as the main valve beneath the barrel was sought. Stirling Moss, watched aghast as his beautiful sports-racer went up in flames, to re-emerge foamy and blackened – driveable remarkably but unraceworthy obviously.

But this was a three-way world championship decider: Aston Martin sage green versus Ferrari’s Testa Rossa – with Porsches buzzing on the fringes.

No time to waste. Within four minutes – and after a remarkably composed pitstop given the hellish circumstances – Moss commandeered the second-placed DBR1/300 from Jack Fairman (rather than it be Carroll Shelby) and set off on one of his famous charges. Within a half hour – just past half-distance – he was back in front. He would drive for 4hr 36min of this six-hour race to score the victory. There was fire in his belly.

1960 BARC Formula Junior

March 19

John Surtees, leading, had never watched a car race let alone entered one. After recent successful tests at Goodwood for Aston Martin and Vanwall, however, the multiple motorbike world champion found himself bundled into a Cooper-Austin by Ken Tyrrell and sitting on pole position at a track of which he had no racing experience.

Alongside him was a man starting only his second single-seater race; the first had been the most underwhelming experience of his car career to date. Though more hopeful on this occasion, he had chewed his fingernails to the quick while mechanics rushed to reassemble and ready his engine. Surtees got the jump. Passed on the second lap, he retook the lead on the fifth. Already amid backmarkers, this battling pair then dived either side of a slower car at Madgwick. Except that Surtees’ gap was bike-sized. Old habits. Forced onto the grass, he dropped to third place – and eventually recovered to second.

The man who beat him – having his first race for Team Lotus and scoring its first win using a Ford engine by Cosworth and sited behind the driver – was a sheep farmer from the Scottish Borders: Jim Clark.

Within months he and Surtees would be Formula 1 team-mates. Within five years they would have three F1 world championships between them.

Crowds at Goodwood for the 1964 News of the World Trophy, with Jim Clark (No1) and Graham Hill (No3) on the front row of the starting grid

Getty Images

1964 News of the World Trophy

March 30

Ferrari’s presence, promised but reneged upon, would have been a bonus – John Surtees would after all win that season’s F1 world title for the Scuderia in dramatic circumstances – but its absence could not prevent this most British of circuits from hosting a truly competitive race of what fundamentally had become a British category. When a front row consisted of Jack Brabham, Jim Clark and Graham Hill – and thus the patriotic greens of Brabham, Lotus and BRM – it was game on.

These teams would battle for supremacy all season long – allowing a resurgent Ferrari to sneak up on them – and on this occasion it was Hill who appeared to hold the upper hand as Clark’s clutch faltered. After 40 of 42 laps, however, the BRM of Hill coasted in, a broken distributor silencing its V8. Brabham having already retired, at three-quarter distance when a broken nearside-rear wheel and resultant puncture plunged him into the spectator banking, it was Clark who coaxed home for victory.

A youthful Jackie Young Stewart – arguably Goodwood’s greatest discovery – had scored a runaway victory in the Junior support race run a little more than an hour earlier. Twelve months later he and compatriot Clark – the Batman to his Robin – would share Goodwood’s forever fastest contemporary F1 race lap.

Ferrari’s 11-year title wait was just beginning – though Goodwood’s 32-year slumber lay just around the corner.