British Racing Partnership — pushed out by the establishment?

Based in London, the British Racing Partnership was a pioneering outfit, yet its F1 existence in the ’60s was cut short after six seasons. Ian Wagstaff, author of a new book on BRP, explains the rise and fall of a team denied its place in history

Trevor Taylor drove for BRP alongside Innes Ireland in 1964; he drove a Lotus-BRM in the British GP at Brands Hatch

Klemantaski Collection/Getty Images

During 1964 Brabham, BRM, Cooper and Lotus formed the Formula 1 Constructors’ Association, or F1CA as it was then referred to. Ferrari did not join, but then that was Ferrari. The association created the Paris Agreement, by which most of the starting money paid by grand prix organisers went to F1CA’s members, leaving only crumbs for privateers. It was noted by Formula 1’s newest constructor, the British Racing Partnership (BRP), that it had not been invited.

What would happen would leave a bitter taste in the mouths of some who are still with us and BRP’s founder, Ken Gregory, a disillusioned man.

“I think a lot of it was the jealousy of the other team owners,” says Bruce McIntosh, a young BRP mechanic at the time and now a senior FIA official. “They did not like Ken Gregory because he was making money [out of the sport]. It was much the same as Bernie Ecclestone was later looked at. It was disgusting; I got the feeling that we were being pushed out by the establishment.”

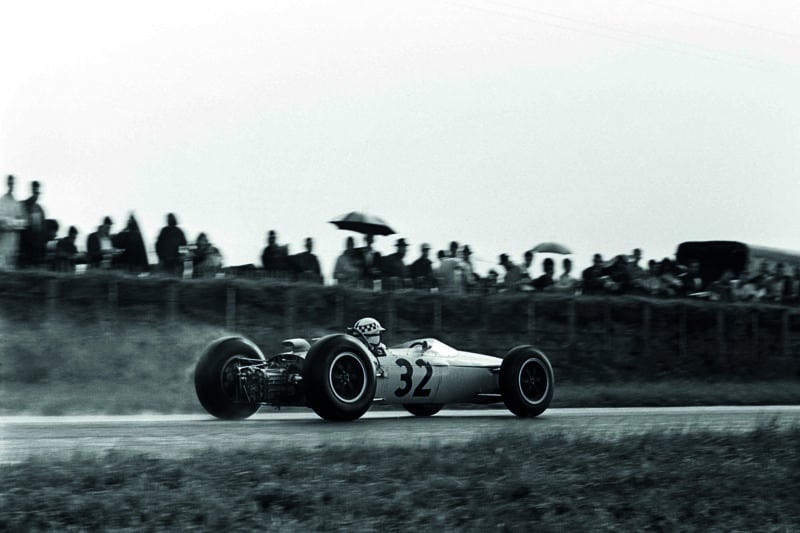

The BRP-BRM had similar looks to the Lotus 25 but had a thicker skin, which gave more confidence to its drivers. Here’s Innes Ireland at the 1964 Italian GP

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

Back in 2013, a week before he died of cancer, I paid a visit to Ken. The snub still grated: “I thought F1CA was an association of hypocrites motivated by fear,” he said.

BRP was in its second year as a constructor and had already won a non-championship F1 race, something that even Team Lotus did not do during its first two seasons at this level. Its chief mechanic, Tony Robinson, reckons that, having crawled in 1963 and then learnt to walk the following season, it would have been running by 1965, musing on the possibility that it could then have achieved the same heights as McLaren. So, what went wrong? Was BRP’s demise solely down to F1CA, or was there more to it and how should BRP be regarded in the light of history?

I first met Ken one cold, wet Sunday afternoon in his office in Beaconsfield during December 1978. By that stage, he had become a publisher and I was there to be interviewed for a job in his editorial department. I recall coming out thinking that this was a man that I did not want to work for. However, he had invited me to an awards ceremony that his magazine was hosting a few days later, where he announced to those assembled that I was about to join the company. It was the first that I had heard of this but I decided to go with the flow and became one of his employees. It turned out to be one of the best decisions I ever made. He was a great, if sometimes controversial, and appreciative boss.

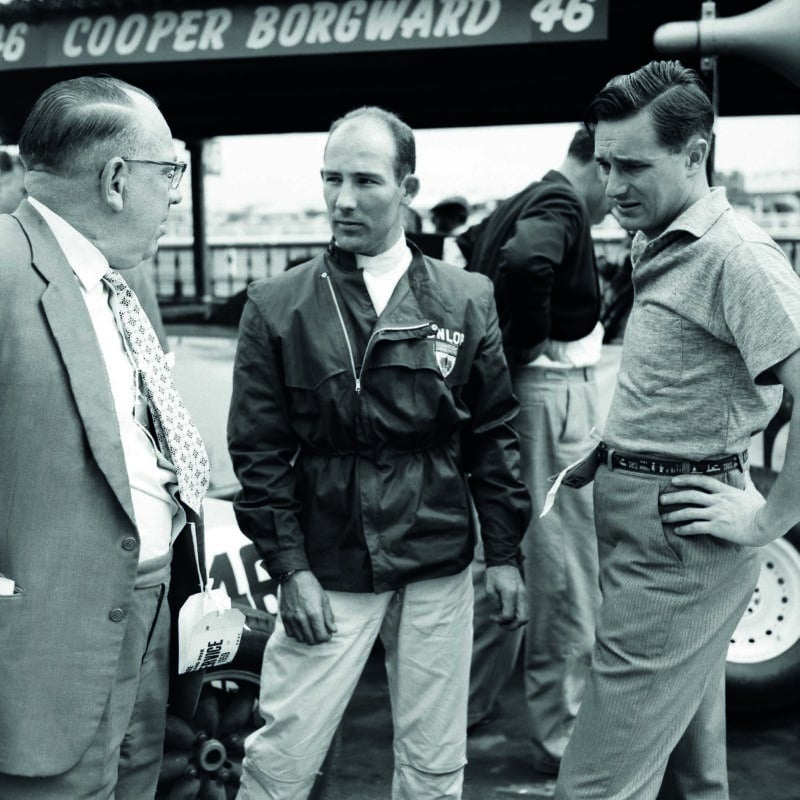

Stirling Moss, centre, and BRP chief Ken Gregory, right; a ‘vexing question’ would mar their relationship

I relate this self-indulgent story in an attempt to illustrate Ken’s nature, something that I reckon was behind the rise, success and ultimate failure of BRP. Those who did not know him were often wary of him, and I believe that the F1CA ‘grandees’ were among these. Those who were closer to him knew that there was more to him than just a man with an eye on the main chance.

The primary requirement for membership of F1CA was that cars had to be, in theory, built by the team and that it should have completed at least one season of F1 competition. The prototype BRP of 1963 had not met this stipulation as it had used Lotus 24 uprights and suspension. However, the two 1964 cars were, as the team’s number one driver Innes Ireland pointed out, at least 90% manufactured by the team itself. True, the engines came from BRM but then all of the F1CA members, with the exception of BRM itself, purchased their power units from an outside source.

“Ken had been traumatised by Moss’s career- ending accident at Easter 1962”

BRP advised F1CA that it was ready to comply with its membership rules and invited the association to inspect its cars at the US Grand Prix. Nobody turned up and Ken got the distinct impression that Andrew Ferguson, F1CA’s secretary, was anti-BRP. The same thing happened at the Mexican GP, the last race of the season, again no inspection. During 1962, BRP missed around £8000 in start money from meetings that it could not afford to attend, while the payment for those that it did go to was very low. At the end of the year it was calculated that the whole operation had lost £7000. Had it been a signatory to the Paris Agreement, it would have broken even.

Gregory could not afford to go on and, having fulfilled an order from Masten Gregory’s stepfather George Bryant to build a couple of cars for the Indianapolis 500, a remarkable achievement in itself, he closed the doors of the team’s Highgate workshop. “How ludicrous it is that such a large and properly organised outfit like BRP cannot afford to race,” wrote Ireland. “I feel that this is an indication of how much ‘sport’ is left within the sport that a fine team like BRP had to go to the wall.”

Having risen in motor sport as Stirling Moss’s manager, Ken had created for himself something of a ‘wheeler-dealer’ reputation. However, the fight had now gone out of him. As he would reflect, the Ken Gregory of earlier years would have struggled harder to preserve his team. He had been traumatised by Moss’s front-line career-ending accident at Easter 1962 (driving a Lotus 18/22 entered by BRP), not only by the serious injuries to what had been a close friend but also by the way in which their relationship had deteriorated in its aftermath. Three drivers, Ivor Bueb, Harry Schell and Chris Bristow had also been killed earlier in BRP-entered cars, which had deeply affected him.

Innes Ireland in the Lotus- Climax (No2, right) lines up at the 1962 Brussels Grand Prix alongside Jo Bonnier (16) and local hero Willy Mairesse (10)

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

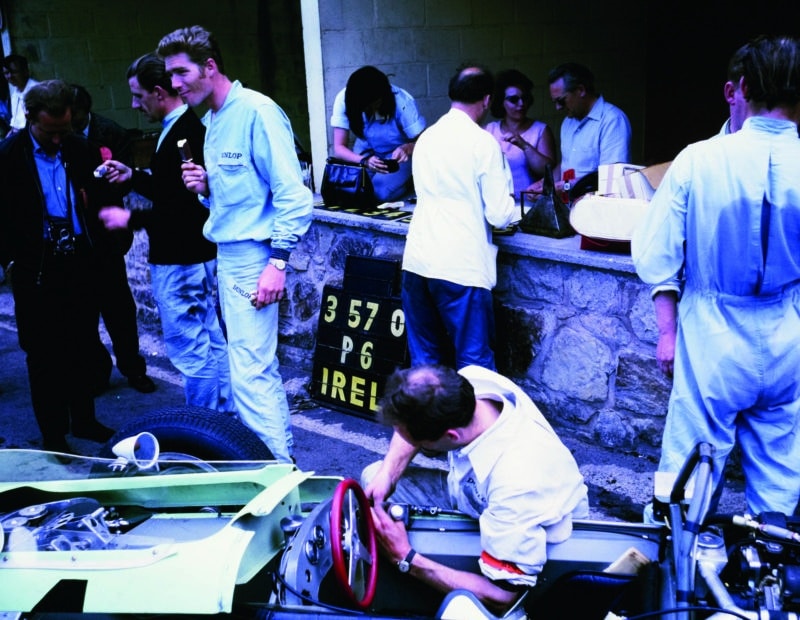

BRP drivers Jim Hall and Innes Ireland, here in pale blue overalls, relax at the 1963 Belgian Grand Prix

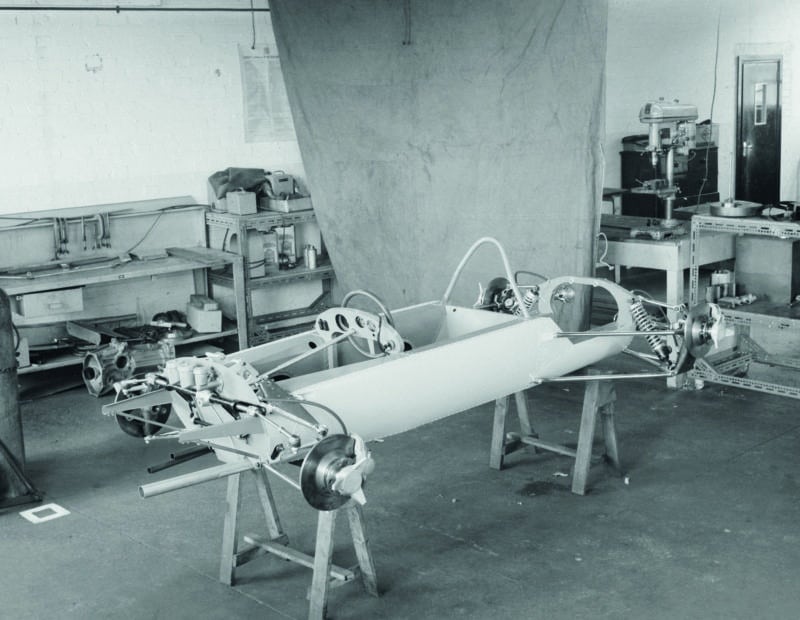

BRP built three Formula 1 cars at its Highgate factory and was later approached to build two Indycars for the 1965 Indy 500

Although it might be said that BRP’s best seasons were still ahead of it, the beginnings of the end can be seen on that April day at Goodwood. One of the team’s mechanics, Ron White, told me, “It all fell through when ‘Mossy’ got hurt.”

Ken admitted that by 1964, “I wasn’t functioning properly.” Even prior to 1962, stress had brought on a duodenal ulcer and severe eczema. Sent by a leading dermatologist to hospital, he was put virtually to sleep for a fortnight.

In late 1959, Ken had done a deal with the Samengo-Turner brothers, who ran the hire purchase company that would make BRP the first fully sponsored Formula 1 team. The Daily Telegraph pointed out that this was “a source of some consternation among racing purists”.

Ken claimed that the deal was worth £40,000 although the Samengo-Turners would later say that it was far less. A year later, the Samengo-Turners formed their own team run by Reg Parnell, but Ken replaced them with United Dominions Trust, a larger rival credit company.

Tragedy followed for Chris Bristow who was killed driving this Cooper for BRP at the 1960 Belgian GP

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

Initially, the team ran Coopers but when Ken went to buy cars for the 1961 season he found Charles Cooper “edgy at lunch”. There would be a considerable delay before any could be delivered. Ken got the impression that Charles’s son, John, was making life difficult, that the manufacturers were beginning to worry that his dealings were creating a better-funded team than themselves. Having said that, it cannot have helped that Ken had been trying to lure Bruce McLaren away from Cooper.

Frustrated, Ken turned to Lotus. He might have met with a similar response as he had also been talking to Jim Clark, but the Scot had now signed for Lotus, so Colin Chapman would not have been as concerned.

The dependence on Lotus led to another occurrence that would gall Ken for the rest of his life. When he ordered four Lotus 24s for 1962, he believed that he would be running cars with an identical specification to the factory. But when the monocoque Lotus 25 emerged from the Team Lotus transporter at Zandvoort, Ken was furious. Driver Ireland, who had been dropped by Chapman at the end of the previous season, was also angry. Mechanic George Woodward, who had been at Cheshunt assembling one of the 24s, says, “we realised that the things we were building were already out of date. I don’t think there were too many businessmen who could get one over Ken but I think he met his match in Chapman.”

Innes Ireland in the BRP Mark II at the Mexican Grand Prix, 1964

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

Ken would gradually become phlegmatic about what had happened. “[Chapman] cheated us but he would have thought that was all right.” He also fought back by asking Tony Robinson and his team to build what would be Formula 1’s second monocoque car.

Ken may have had a fragile relationship with the established constructors but he would still muse on the fact that they did not follow his lead and find their own sponsors. “It was possible that they did not have my background. They would have to have thought laterally which, for me, was normal.” He reckoned that the purpose built UDT-Laystall transporters and the smartly attired mechanics made BRP “a team to envy”, admitting that “our professionalism could have been seen as brash”.

To this could be added that Ken was not ‘one of them’. True, he had been a garage mechanic before joining the Army Technical School, where he received engineering training, but he was not an engineer in the mould of Chapman or BRM’s Tony Rudd. It was felt, perhaps, that his commercial approach gave him an unfair advantage. True, BRP had lost its sponsorships by the time that it built its own cars but there may have been a fear that, Ken being Ken, this was only a matter of time.

Ken would admit that he was not everyone’s favourite team manager but there would be another snub that he could never understand. On more than one occasion, BRP was inexplicably excluded from the German Grand Prix. In 1962, Motoring News suggested initially that this was because the team had “words with the AvD [Automobilclub von Deutschland] over starting money”. A week later, the newspaper was incandescent on behalf of the team. It had been nothing to do with start money; it had never got that far.

Off the pace at the 1963 French GP at Reims for Innes Ireland in the BRP-BRM – ninth on the day

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

When Ken had requested entries, the AvD had replied that since its drivers Ireland and Masten Gregory had “made poor performances at the Nürburgring” they were not interested in having UDT entries unless the cars had placed in the first six in the preceding French or British Grands Prix. This was the Innes Ireland who had won the previous year’s US Grand Prix at Watkins Glen and who would be on the front row of the grid at Aintree. Motoring News remarked, “discrimination is all very well and good… but if the Club has something to say against UDT-Laystall why not say so frankly?”

“We always had trouble with Germany,” remembered Ken.

BRP secretary Celia Ercolani recalled he “was always out to make money, he needed to do that, and that did not always endear him to everybody”. He was an opportunist and that did not sit well in the Formula 1 world of the mid-1960s although one is tempted to think that it would have fitted in well in the commercially driven grand prix world of later years. Bernie Ecclestone, himself, agrees that BRP paved the way forward for F1.

History has not necessarily been kind to BRP. It has been said that it was set up “to run cars for Stirling Moss”, which was not the case, although he would sometimes take advantage of the team of which his father Alfred was co-owner. The F1 BRP-BRMs have been described as less competitive than the Lotus 24s that they replaced but it has to be pointed out that the team had hardly got going as a manufacturer when it was forced to close. However, the BRPs were beautifully built and strong, which meant extra weight, something that was appreciated by the drivers and let us not forget Ireland’s win at Snetterton with one of them. One writer has described the Indianapolis cars as “pretty hopeless”. Tell that to the drivers that Masten Gregory overtook during the opening laps of the 1965 ‘500’. As Competition Press & Autoweek said, “Gregory finally got himself a decent car for the race and put on one of the few really dazzling displays of driving

in the entire event.”

BRP’s swan song was the Indy 500 in 1965; Johnny Boyd was in this BRP-Ford but failed to finish

Getty Images

Masten Gregory in 1962, when the team was known as UDT-Laystall

Moss racing in the Player’s 200 Mosport under the United Dominions banner

Following the team’s demise, Ken believed it had been agreed that the three Formula 1 cars would be divided between himself and Alfred and Stirling, the latter having become a director of the team. However, all went initially to Moss Jr’s own operation, SMART. “It was the last I saw of them,” said Ken.

“We of BRP have the happiest band of mechanics in motor racing”

In 1997, he corresponded with Stirling about the matter. It was not the last such letter and, as late as 2009, he wrote that he could not understand why they had still not solved “the vexing question”. The following year, the now Sir Stirling sent £10,000 in payment for Ken’s car. There had obviously been friction between the two, but Ken was now able to write back, “Now I know and can appreciate the true meaning of friendship.”

During the time that I was in his employ, I had the impression that, although he would still attend the British Grand Prix as a judge, Ken had left motor racing behind him, arguably hurt by what the sport had done to him. Perhaps hubris had got the better of him. However, many years later, he asked me to assist in the writing of a second part to his 1960 autobiography Behind the Scenes of Motor Racing. Our conversations gave me a new insight into what BRP had achieved. He died before many words were written but our discussions, I felt, had given me the opportunity to put the case for BRP’s unique – and I use the word advisedly – position in the annals of motor racing.

Innes Ireland gives a ride to Jo Siffert on his BRP-BRM at the Belgian GP 1964

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

BRP ultimately failed. However, there is much that should be celebrated about the team and, having learnt of Ken’s pride in it, I reckoned that it should be recorded for what it was.

I am grateful to Evro Publishing’s Mark Hughes for coming up with the title for the resulting book Formula 1’s Unsung Pioneers, for that is what the men at BRP were. However, it is not just because it introduced grand prix racing to the volume of finance that revolutionised the sport. There were also times when it was highly successful. It won the RAC Tourist Trophy at Goodwood with a Ferrari 250 GTO that also led the GT class at Le Mans and went on to become, at one point, the most expensive car ever sold. It was also a serial winner in British sports car racing with three Lotus 19s. Ken admitted that he would go “pot hunting” and sponsorship money did enable him to swamp the opposition but it was still an impressive display by his sports racers.

To the above can be added that BRP was a pioneer of pits-to-cockpit radio. And one must not forget that it supplied free beer to all the mechanics in the paddock, whatever their team, from the back of its transporter. The BRP men also built their own monocoque Formula 1 and Indycars, not a bad achievement for a bunch of mechanics with little design experience.

The way those mechanics comported themselves should also be noted. “We of BRP,” wrote Ken in 1960, “have the happiest band of mechanics in motor racing, and as long as we keep it that way, our drivers will be happy too.”

A final appearance at the British GP for BRP; in 1964 Innes Ireland (No11) finished 10th at Brands Hatch but took victory that year at Snetterton in a non-championship race

Grand Prix Photo

Trevor Taylor lasted a fifth of the race at the 1964 Austrian Grand Prix

You can take the boy out of Yorkshire… Taylor had distinctive head protection

From the start, Ken had said, “There were standards which we intended firmly to maintain. We believe not only that a car should be mechanically perfect but that it should appear on the circuit immaculate. We believe that not only should the car be spotlessly clean, but that the mechanics and driver should be the same.” It was a mission statement with ideals that the team would adhere to and which the press would often note in the coming seasons.

Stirling Moss certainly had faith in the BRP mechanics. When it was decided that he should drive a BRM Type 25 in certain grands prix during 1959, Moss insisted that the car be stripped down and rebuilt by Tony and his men before he would drive it. The car, it was observed at the time, was “scrupulously assembled”. BRM mechanic Dick Salmon would record that “the arrangement was not very well received at Bourne” but even BRM boss Sir Alfred Owen had been able to appreciate the benefits of BRP’s methodical way of sorting and setting up a car.

Ken’s biographer Robert Edwards wrote that if BRP had been allowed to join F1CA, he “in all likelihood would have ended up running the whole thing. The man who effectively did, Bernie Ecclestone, owes much of his success to the blueprint that was laid down by Gregory as the original Formula 1 entrepreneur.”

Ferraris dominated the Goodwood TT in ’62, with Ireland topping a 250 GTO 1-2-3

McIntosh, who has known both men well, believes that they have been misunderstood in the same way. On hearing that the European Grand Prix was to be held at Valencia, a two-hour drive from where he then lived, Ken contacted Bruce, who he knew was working with Ecclestone, wondering if he could procure a couple of paddock passes. His former mechanic contacted the Formula 1 boss, asking him if he knew Ken. “Of course I bloody well know Ken Gregory,” was the response.

The two went back to their time in 500cc Formula 3 racing and Ecclestone had been both the friend and manager of Stuart Lewis-Evans, who had been BRP’s first driver. Not only would there be tickets but Ken and his wife Julie were to be escorted to Ecclestone’s enclave the moment they arrived. There the two old acquaintances talked for over an hour before Ken and Julie were sent to enjoy the pleasures of the Paddock Club. “He was over the moon,” recalls McIntosh. Perhaps it could be said that Formula 1 welcomed Ken Gregory home that day.

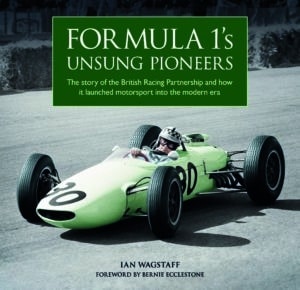

Formula 1’s Unsung Pioneers: The Story of the British Racing Partnership and How it Launched Motorsport into the Modern Era

Formula 1’s Unsung Pioneers: The Story of the British Racing Partnership and How it Launched Motorsport into the Modern Era

by Ian Wagstaff

Published by Evro, £95

Formula 1’s Unsung Pioneers: The Story of the British Racing Partnership and How it Launched Motorsport into the Modern Era

Formula 1’s Unsung Pioneers: The Story of the British Racing Partnership and How it Launched Motorsport into the Modern Era