My interest in F1 developed after James won the world championship in 1976. Two years later the BBC began broadcasting highlights of each race on a Sunday evening with Murray’s tones bringing the weekend to a climactic finale. When James joined the BBC team in 1980 his driver’s-eye view added a valuable perspective but I was completely oblivious to the fact that their relationship was tricky. Murray felt under threat; most commentaries then were done by a single announcer and he thought James was there to steal his slot. In fact it was the beginning of a new period in broadcasting where sports stars went on to become vital communicators and gradually the tension eased, although it never fully disappeared.

After a decade of working together things could still go wrong. For the grand prix in Adelaide in the early 1990s, James and Murray worked directly with Australian broadcaster Channel 9 on site as well as providing BBC commentary. Mark Wilkin was there to keep an eye on them but they had separate briefings from a feisty local producer who irritated James while Murray was happy to co-operate. One meeting went particularly badly; Mark was at the hotel when he got a call and had to hold the phone away from his ear:

“YOU WON’T BELIEVE WHAT JAMES DID IN THE MEETING!” Murray bellowed and continued to rant for 20 minutes.

“I told him I would sort it out and rang James,” remembers Wilkin, “and he said, ‘Well, you won’t believe what Murray did in the meeting,’ and off he went for 20 minutes. I said the only way we can sort this out is to have dinner together.”

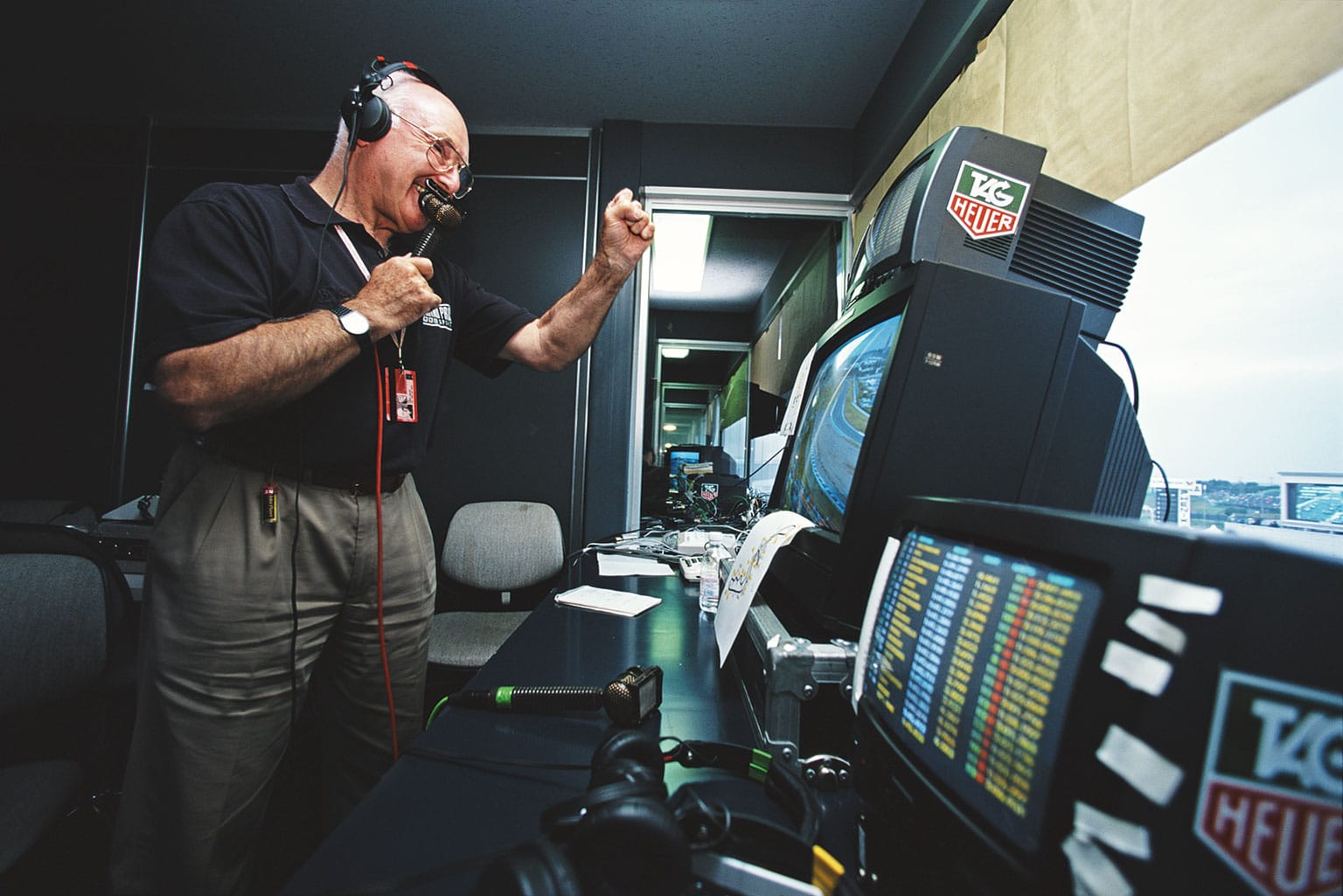

National treasure at Silverstone for the 2010 British Grand Prix

Always one to know the best venues in the area, Wilkin booked a restaurant nearby and prepared to play a diplomatic role.

“It was the most uncomfortable, most unpleasant dinner I’ve ever had. Both of them refused to back down. Murray absolutely adored Australia and it oozed out of every pore of his commentary what a fabulous place it was. But James hated it, claiming there was no culture.”

They still had some aspects in common as both decided to order the same chicken dish. Tension was hanging in the air but before long the waiter appeared, carrying two very generous plates.

“SEE, THAT’S WHAT’S SO MARVELLOUS ABOUT THIS COUNTRY, LOOK AT THIS CHICKEN HANGING OFF BOTH SIDES!” enthused Murray.

“It’s typical of this country they’ve got to have it bigger and better,” moaned the moody Hunt. “Isn’t that an example of how awful this place is?”

Thankfully the benefits of good food and drink did calm the situation and Mark’s plan allowed the weekend to go ahead as normal. “Eventually we got round to discussing it and saying it’s okay to have different opinions and they became friends again.”

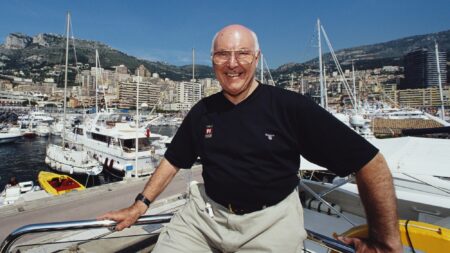

Murray and James Hunt in 1983; at times, this was a spiky pairing

It was clearly a complicated relationship throughout its duration, one that so sadly came to a premature end in 1993 when James died at the age of 45, but the combination will always be remembered for delivering a fantastic mix. Ironically, my early F1 partner John Watson influenced Murray on one occasion without even knowing it. The commentary booths at Spa in the 1990s were not much bigger than phone boxes. Two people could squeeze in, but Mark’s role as commentary producer had to be operated from a separate booth. It was a year or two before John and I worked together and he wasn’t commentating that weekend. He asked Mark if he could watch the race from his cabin and he was duly set up with some headphones then focused on the action.

It proved an entertaining time. With Murray’s commentary in one ear, John Watson’s voice was filling his box with observations. “Oh Murray, what a bloody idiot, that’s Prost not Mansell,” shouted Wattie, and then a few moments later, “He’s going to have to come into the pits now.”

Within a breath, Murray was calling, ‘OH, HE’S GOING TO HAVE TO COME INTO THE PITS NOW!’ and Mark presumed they had both been inspired by similar thoughts as the pattern kept repeating.

The truth was slightly different. For some reason, the normal ‘press to talk’ button had remained open: “Unknown to me, Wattie had been audible the whole time into Murray’s ear,” says Mark, “but he hadn’t thought to tell me at some stage that he could hear this strange voice.”