Team pact under threat

An argument over the Resource Restriction Agreement is threatening the future of FOTA, the F1 teams' organisation. Some teams are convinced that Red Bull Racing is spending more than it…

A landmark day in motor racing history, as the first Monaco Grand Prix took place on a course slightly shorter than the one we know today, though much of the layout hasn’t really altered. Englishman William Grover-Williams, racing simply as ‘Williams’, fought off an early challenge from Rudolf Caracciola’s Mercedes SSK and led for most of the 100 laps. His Bugatti T35B crossed the line more than a minute ahead of Georges Bouriano’s T35C, with Caracciola having slipped to third.

Alfa Romeo withdrew in the wake of a tyre row (it was contracted to Pirelli, but wanted to run on Dunlops), but there were strong entries from Maserati and Bugatti. The latter’s T51s were favourites, but with grids still being drawn by ballot, Achille Varzi and Louis Chiron, above, started on row four. Varzi worked his way to the front, but a broken wheel handed the initiative to Chiron. He led thereafter and became the first and only Monégasque to win a home race.

Bernd Rosemeyer’s Auto Union having been sidelined by steering failure, the Mercedes W125s of Rudolf Caracciola and Manfred von Brauchitsch dominated. They fought until a lengthy stop delayed the former, but a jammed front brake cost von Brauchitsch time in the pits. He retained his lead, with Caracciola just behind, and ignored signals to let his team-mate pass. He acquiesced once he knew Caracciola needed to stop for tyres. Team orders are no new invention.

Eight days after its Silverstone dawn, the World Championship featured Ferrari for the first time – though Alfa Romeo’s 158 was the car to beat. Juan Manuel Fangio was clear of a pile-up on the opening lap, but next time around, he noticed the crowd looking in the other direction, rather than at him, and slowed. It played a vital part in his victory.

Ferrari’s maiden Monaco GP victory was scored not by a grand prix car, but by a 225 S. Absent from the World Championship from 1951-54, the event took place once during that time – and, uniquely, catered for sports cars. Stirling Moss led in his Jaguar C-type but ceded to Robert Manzon’s Gordini before a multiple collision claimed both. Vittorio Marzotto went on to head a Ferrari 1-2-3-4-5. The weekend was marred by Luigi Fagiioli’s serious practice accident; he succumbed to his injuries almost three weeks later.

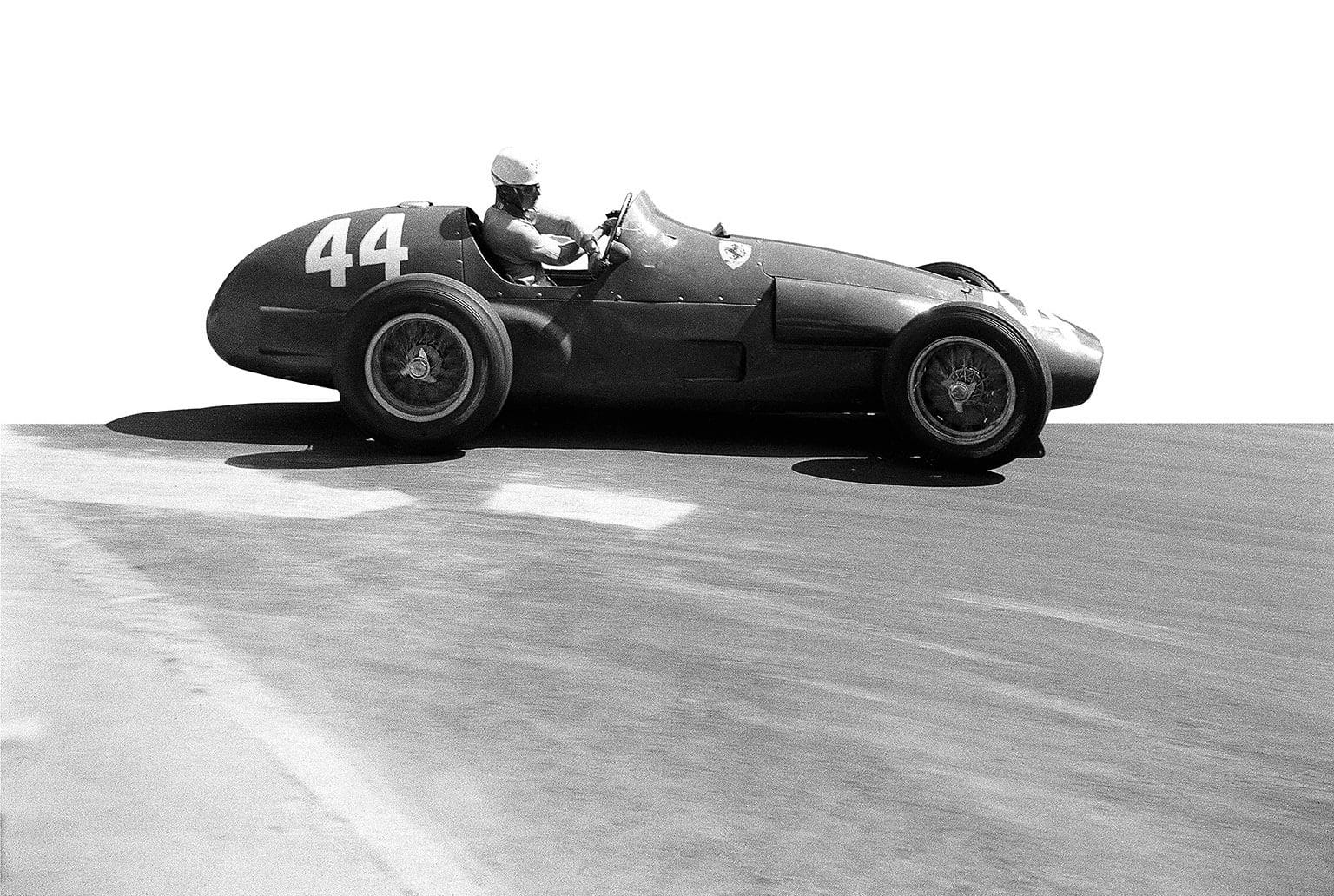

The Mercedes W196s dominated, of course, but transmission failure accounted for Fangio – and Moss’ engine blew. Alberto Ascari’s Lancia sailed into the lead… but then into the harbour after a mistake at the chicane. The double world champion emerged with cuts and bruises, but died four days later when he crashed a Ferrari 750 during a Monza test. Maurice Trintignant, above (Ferrari 625), emerged as the winner; it was a first World Championship success for Englebert tyres.

Having dominated the opening GP of the season in South Africa, Jim Clark and Team Lotus skipped the second because they were away winning the Indy 500. Graham Hill, above, scored his third straight victory in the principality, but it wasn’t that simple. He dropped to fifth after being forced down an escape road, then pushed his car back onto the track before launching a recovery. Paul Hawkins was the harbour’s second visitor after crashing DW Racing’s Lotus 33. He swam back to shore.

Jackie Stewart controlled the race until a misfire set in, handing the initiative to Jack Brabham. Jochen Rindt had qualified only eighth in his ageing Lotus 49, but moved up to second thanks to others’ misfortunes – and scented victory. With 18 laps to go he was 9sec adrift, but the gap quickly shrank. At the very last corner Brabham locked up and slid wide. Rindt nipped through to win, having completed his final lap in 1m 23.2sec, 0.8sec under Stewart’s pole time.

Jean-Pierre Beltoise had yet to score a grand prix victory and his F1 career was approaching its twilight, but for one afternoon the stars aligned. His BRM V12’s torque was useful on a treacherously wet surface – and the slow pace meant his withered left arm, the consequence of an accident at Reims in ’64, was less of an issue than usual. A banzai start catapulted him into the lead from row two – and he stayed there to score BRM’s final F1 success.

Gilles Villeneuve was a thinking driver with a delicate touch – and here was a case in point. No mug at the wheel, Didier Pironi qualified his Ferrari 126CK 17th, which was probably about par; Villeneuve, 2.478sec quicker, lined up second. He didn’t attempt to race the nimbler DFV-powered cars, but paced himself. Nelson Piquet crashed his Brabham, Alan Jones’ Williams suffered fuel-feed problems… and Villeneuve cashed in.

René Arnoux started from pole in his Renault, but spun off. Team-mate Alain Prost took charge, then crashed with two laps to go. Advantage Riccardo Patrese, above, who spun and stalled his Brabham. Didier Pironi then took over, but his Ferrari misfired on the last lap. Andrea de Cesaris ran out of fuel before he reached Pironi’s stricken car, Derek Daly’s gearbox seized… and Patrese came through to win, having rejoined via a downhill bump start.

Alain Prost, below, led away in heavy rain… until passed by the Lotus of fellow front-row starter Nigel Mansell, who headed a grand prix for the first time. The Englishman swiftly pulled clear, but then slid off the road at Massenet. With conditions not improving, and upstart rookies Ayrton Senna and Stefan Bellof catching leader Prost, race director Jacky Ickx decided to throw the red flag. Prost thus won, but the most admiring glances were reserved for his fellow podium finishers.

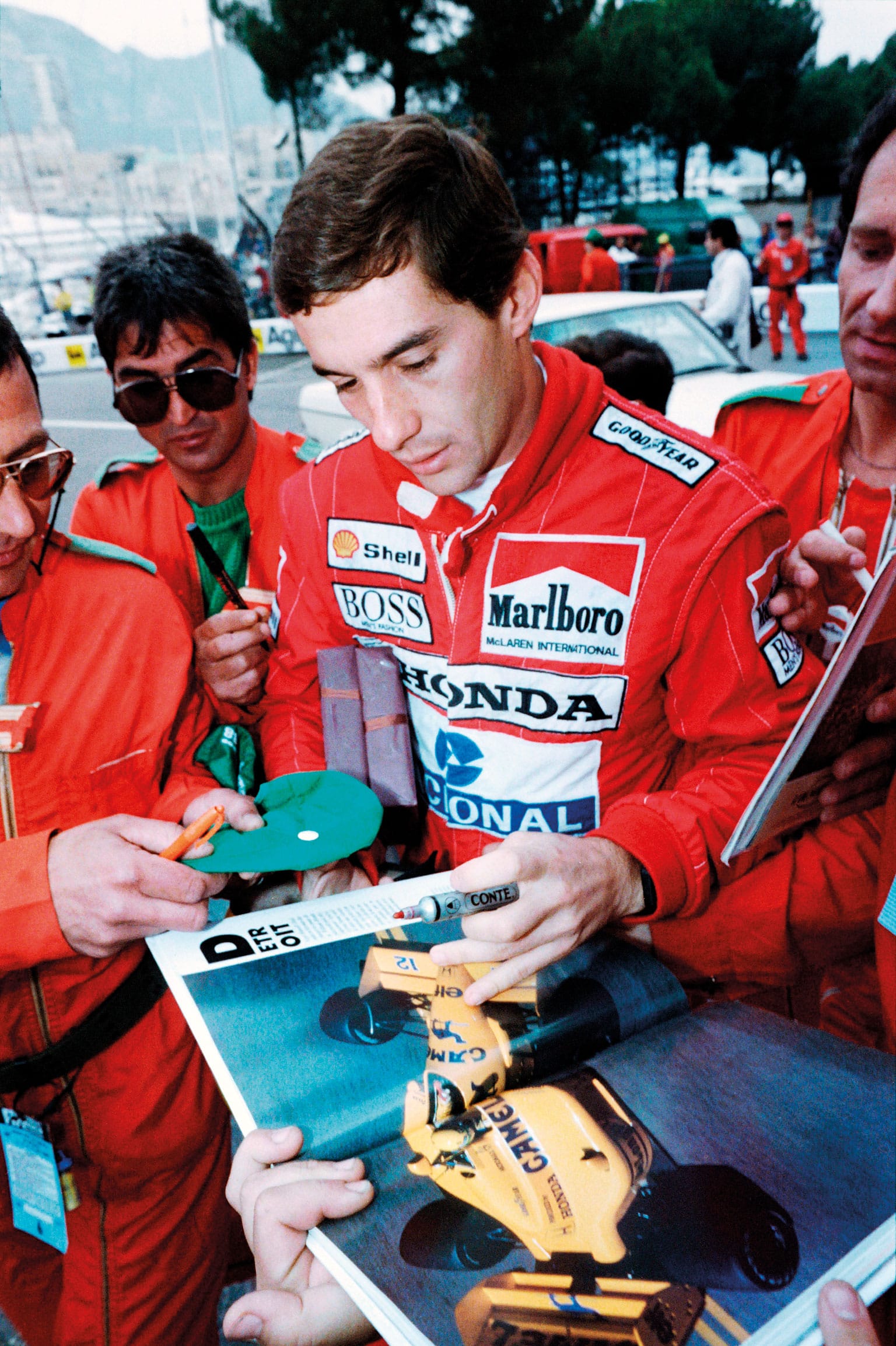

“On that day, I said to myself, ‘That was the maximum for me; no room for anything more.’ I never really reached that feeling again.” Slightly unsettled by this, Ayrton Senna, above, parked up – but pole was already secure. It wasn’t the fastest lap of Monaco – that had been set a year earlier, when the turbo cars were allowed greater boost pressure – but it was 1.4sec quicker than Alain Prost, pole-sitter here just two years earlier.

Given the previous day’s events, Senna predictably romped away. As Denis Jenkinson noted in Motor Sport, “The Brazilian pulled out an incredible lead. Even when he caught tailenders, they hardly slowed his progress, his remarkable vision and judgement taking him through gaps that rivals looked on with disbelief.” On lap 67, however, a slight error pitched him into the rail at Portier. He didn’t hang around to watch, but walked home to his flat to reflect. He would win the next five…

Nigel Mansell, above, had dominated the opening five races of the campaign – and looked set to triumph again, for a first time in Monaco, after storming away from pole. With eight laps to go, a loose wheel forced a stop and allowed Ayrton Senna to lead. On fresh rubber, Mansell caught the Brazilian and spent the final laps weaving in a bid to unsettle him. Senna calmly placed his McLaren in a position that rendered passing impossible. Game over.

Michael Schumacher took pole, but lost out at the start and then crashed at Mirabeau Inférieur. Pressure off, Damon Hill built up a huge lead only to retire when his engine blew. Jean Alesi took over until his suspension failed… and Olivier Panis, below, came through from 14th on the grid to score his only GP win, and Ligier’s last. Panis pulled off some robust manoeuvres, including one to swat aside Eddie Irvine at the hairpin – the kind of thing for which he’d probably be guillotined nowadays.

Jarno Trulli, above, with Renault team boss Flavio Briatore, had looked a certain future winner after he’d led the 1997 Austrian GP, his last scheduled start for Prost, but it hadn’t happened. Having taken pole at Monaco in 2004, his drought looked set to end until a safety car created a potential jumble. Michael Schumacher didn’t pit, unlike most front-runners, but tangled with Juan Pablo Montoya while the race was neutralised. Trulli was back in charge; his only GP victory followed.

Qualifying looked tight between title rivals Fernando Alonso and Michael Schumacher, above. Quicker on the opening run, the German was first to take to the track for a second, but didn’t complete the lap, clipping the wall at Rascasse and bringing out a yellow flag that denied the rest any chance to improve. Footage showed him steering left despite his intimate knowledge of the circuit… He protested his innocence, but was sent to the back of the grid.

Felipe Massa’s qualifying lap, above, as explained by Ferrari race engineer Rob Smedley: “He’d been braking too early for Sainte-Dévote and said he couldn’t leave it any later. I grabbed him by the scruff of the neck and said, ‘D’you want to let the whole of Brazil down here, because you’re letting me down?’ He then braked 32 metres later. I’m fairly sure he was trying to prove that he’d end up in the barrier, but then he realised, ‘I’ve got through!’ That was it, pole.”

Two years earlier, Daniel Ricciardo, above, had dominated the race from the start, only to drop behind Lewis Hamilton after a rare Red Bull pit fumble. This time he led once again, only to lose a significant amount of power at one-third distance when his MGU-k failed. Thereafter he had to manage not only that, but also various side-effects – including overheating rear brakes. Despite the circuit’s labyrinthine nature, he didn’t put a wheel wrong – a victory that was richly deserved.