Stirling Moss in Nassau: The Calypso Kid

Our hero was a regular visitor to the Bahamas for ‘50% racing and 50% fun’. In an exclusive extract from his new book, Richard Williams takes us back to the sun and sounds of Speed Week

‘‘Nassau,” the US journalist turned racing driver Denise McCluggage wrote, “was a string of coloured lights across a tropical night. Nassau was the sharp blip of racing engines on a sun-drenched dock, the soft boiling-fudge speech of the Bahamians selling straw hats along Bay Street. Nassau was an umbrella-drink concoction of star-dipped nights, white sands, conch fritters, a sea rimmed in turquoise (and as clear as gasoline), and racing, racing, racing.”

On Stirling Moss’ first visit, before there was any racing there at all, he fell in love with the place. He enjoyed it so much during the short visit at the end of 1953 that he returned a few weeks later and would pay regular visits in the following years. It was part of the sterling area, which, in the days before the invention of credit cards, meant there were no restrictions on how much cash could be taken in or out, and its climate in the months of the European winter made it an attractive alternative to the popular French Riviera.

On his second visit, in February 1954, Moss spent a fortnight at the British Colonial Hotel. In conversation with its owner, Sir Sydney Oakes, and the holidaying English sports car manufacturer Donald Healey, talk turned to the possibility of staging a motor race on one of the island’s airfields. The initial idea belonged to an energetic and volatile American, Sherman ‘Red’ Crise, who had imported liquor from the Bahamas during Prohibition and promoted midget car racing in his native New Jersey. Crise invited the famous English driver to take a look at the disused Windsor Field. Clearly the advice was positive, because when Moss returned in February 1955, he was given reports of the first Nassau Speed Week, held three months earlier.

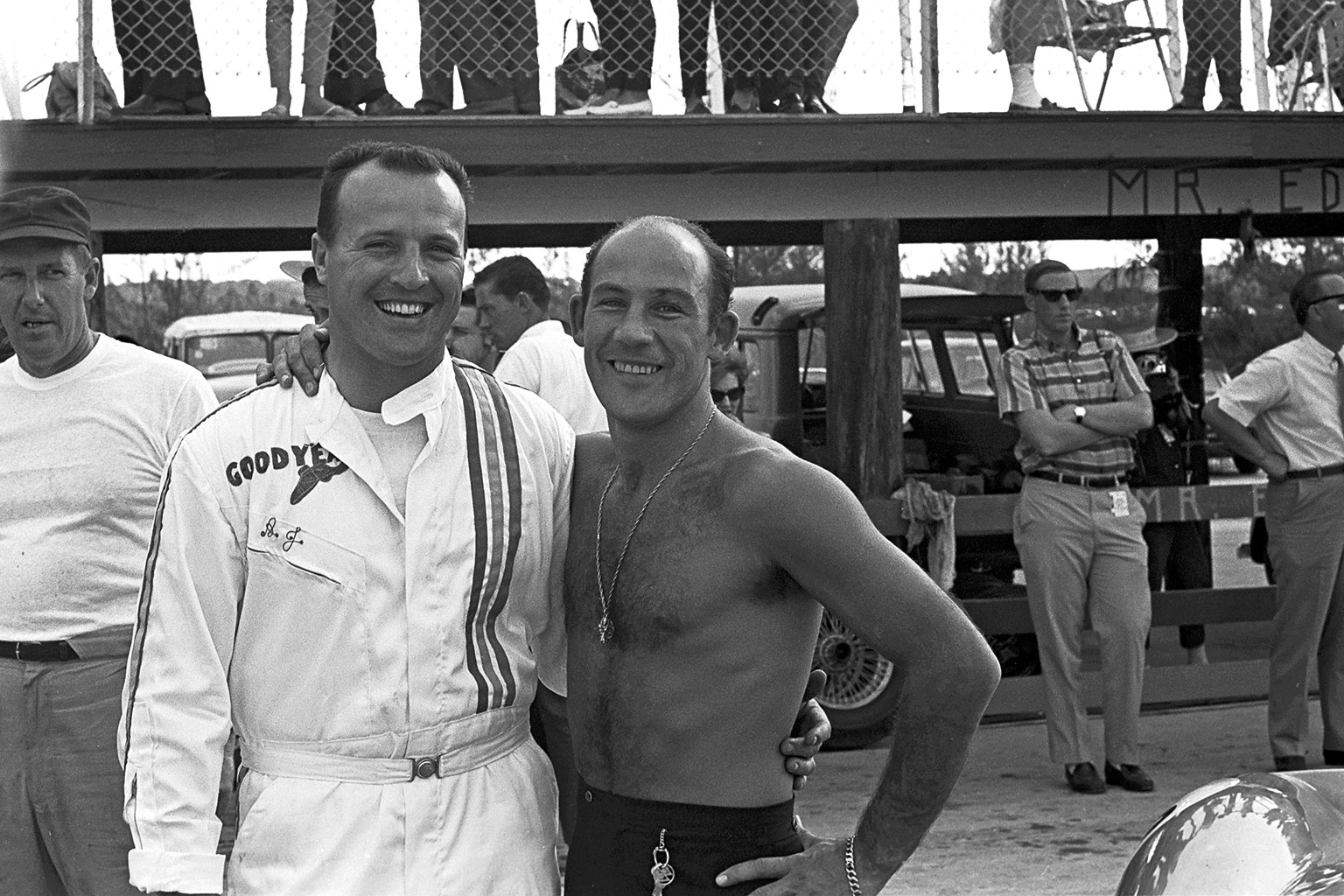

Busman’s holiday for AJ Foyt and Moss, 1963

The newly created Bahamas Automobile Club was chaired by Crise; its president was Oakes, who was also a member of the Nassau Development Board. Sir Sydney owed his hereditary title to his late father, Sir Harry Oakes, a gold-mining tycoon whose gruesome murder in 1943 had made Nassau a focal point of international attention. Various theories were advanced. A French yachtsman who had eloped with Sir Harry’s beautiful 18-year-old daughter was arrested, tried and acquitted, but almost 80 years later the crime remains unsolved.

The scandal added a certain dark glamour to Nassau’s reputation, which blossomed in peacetime. Sir Sydney, having succeeded to his father’s baronetcy, was keen on the idea of a race meeting as a splashy start to the tourist season. His marriage to a strikingly good-looking and vivacious Danish woman, Greta Hartmann, had made the dashing couple symbols of the resort’s growing appeal to the international jet-set.

As a sporting event, the Nassau Speed Week was a combination of Royal Ascot, the Henley Regatta and the pre-war Brooklands meetings, but with even more social activity and a guarantee of better weather. “We like to think it’s 50% racing and 50% fun,” Red Crise said. Throughout the week the night life would be in full swing at the Pilot House Club, Dirty Dick’s and Blackbeard’s Tavern.

Le Mans-style start in 1955

Among those drawn to this festival of speed were wealthy American sportsmen who had acquired the habit of buying European sports cars, either for themselves or for professional drivers to race. That first year brought Austin Healeys, Ferraris, MGs and Jaguar XK120s – one with a Confederate flag painted on the driver’s door – shipped across the 150 miles of water from Miami, the competitors’ travel and accommodation expenses met by the Bahamian government. Alfonso de Portago and Masten Gregory were among the winners, both in Ferraris.

When Moss returned in December, it was to take part himself. He was a member of the Nassau crowd now, watching firework displays from Red Crise’s yacht, dining with Sir Sydney and Lady Greta, enjoying the nightly black-tie parties.

The two big races, the Governor’s Trophy and the Bahamas Automobile Cup, were won by the Ferraris of de Portago and Phil Hill. Stirling’s Austin Healey 100S, entered by Donald Healey, was completely outgunned by the bigger machinery.

Winning ways in 1956 for Moss at Windsor Airfield in a Maserati 300S. Competition included Masten Gregory and Alfonso de Portago

In 1956 he took his parents and sister Pat along for a Speed Week holiday. This time he was more suitably equipped, at the wheel of a Maserati 300S, with which he won the 200-mile Nassau Trophy. The 40 starters included three Chevrolet Corvettes entered by the factory, an indication of the event’s growing prestige. By now Sir Sydney and his wife were divorced, although they remained fixtures at the event and the newly unattached Greta drew admirers – particularly among the visiting drivers – like moths to a scented candle.

For 1957 the Speed Week moved from the scruffy Windsor Field to a five-mile course laid out on the runways of the more modern Oakes Field. Moss arrived with a works Aston Martin DBR2: after finishing fourth in the Governor’s Trophy, he lent the car to Ruth Levy for the Ladies’ Race, only for her to roll and wreck it while battling with the Porsche of Denise McCluggage.

Not wanting the spectators to be deprived of further chances to see their star attraction, the committee persuaded a Dutch amateur named Jan de Vroom, a US-based importer of Italian glass and lighting, to lend Moss his 3.5-litre Ferrari 290MM. Moss repaid the generosity with two wins, including the Nassau Trophy. Six years after being humiliated by Enzo Ferrari when an entry promised for the Bari Grand Prix failed to materialise, these were his first-ever races in a car built in Maranello. De Vroom’s car had been bought for him by his lover, a Rockefeller heiress; his brief racing career was long over by the time he was murdered in his New York apartment, his throat cut by two hustlers, in 1973.

A parade of power through town in 1955. The white Austin-Healey 100 was driven by American JB Orr – a Speed Week regular

It was during one of Stirling’s early visits to the Bahamas that he met Katie Molson, the daughter of a Canadian brewery tycoon, who was working at a local theatre while staying there with an aunt. She was 18 and he was 24. They shared an interest in water-skiing – at which, along with snow skiing, clay-pigeon shooting and fly-fishing, she was an expert – and began seeing each other regularly after meeting up again at Le Mans in 1956. They married the following year, and started building a holiday home in Nassau, a two-bedroomed house designed by Stirling, called Blue Cloud.

Having missed the 1958 Speed Week after a row over starting money, he was back with the DBR2 in 1959, winning a third Nassau Trophy. In 1960 he took part in the only kart race of his career, finishing 13th, before winning the Nassau TT in Rob Walker’s Ferrari 250GT SWB. On his final competitive visit, in 1961, he repeated the win with the same car but retired from the Nassau Trophy when the rear suspension of his Lotus 19 collapsed.

The Speed Week continued until 1966, after which it was decided that a much-needed restoration of the track would be overly expensive to justify its survival. Perhaps, too, some of the social appeal of motor racing had started to fade as the professionals displaced the playboys.

It must be the English accent: Moss attracts attention at the Windsor Field Road Course in December 1955

Katie and Stirling had parted company in 1960. Both of them married again, and divorced again, and eventually Stirling was married a third time, to Susie Paine, with lasting success. Over the years he and Katie rebuilt their friendship. He had given her Blue Cloud as part of the divorce settlement and she continued to live in Nassau, a patron of the arts and of various charities. When a film crew arrived to shoot sequences for Thunderball in 1965, it was Katie who shot the clay pigeons at which Sean Connery appeared to be aiming. In 2015 she returned to Montreal, where some of her time was spent helping in a women’s shelter. She died on April 15, 2020, three days after Stirling.

- An impressive line-up in 1955. In the foreground (No 39) is American driver James Lowe’s Frazer Nash Le Mans Replica Mark II

- The pitlane, Bahamas style, 1955 – pre-suntan lotion era

- Catching some air on the waves at Nassau, March 1955; three days later Moss was racing in the 12 Hours of Sebring

The Boy: Stirling Moss – A Life in 60 Laps by Richard Williams is published in hardback by Simon & Schuster. It is available from April 1, priced £20.