Obituaries

Chris Meek He may have come to motor racing as a driver, but Chris Meek left his mark as the colourful owner and driving force behind Mallory Park race circuit.…

Close your eyes and think of Stirling Moss racing on a home circuit, and the chances are you will be imagining him at Aintree, where he won the British Grand Prix in 1955 and 1957, or at Goodwood, where he raced a 500cc machine at the circuit’s inaugural meeting in 1948 and went on to win the Tourist Trophy at the circuit four times, and where a still-unexplained crash on Easter Monday 1962 ended his professional career.

Silverstone is unlikely to be the setting that most readily springs to mind. And yet, over the 15 seasons of his career as a professional racing driver, Moss started 48 races at Silverstone, winning 22 of them. The fast sweeps of the converted bomber base in Northamptonshire turned out to be a fine stage for his versatility and virtuosity.

His first visit had come in October 1948. He was fighting for the lead in a support race at the inaugural British GP meeting when the engine drive sprocket of his Cooper-JAP worked loose on the last of the three laps. In the equivalent race the following year he registered his first Silverstone victory in the 500cc heat and finished second in the final after a piston broke with the finish line in sight, an early glimmer of the famous Moss jinx.

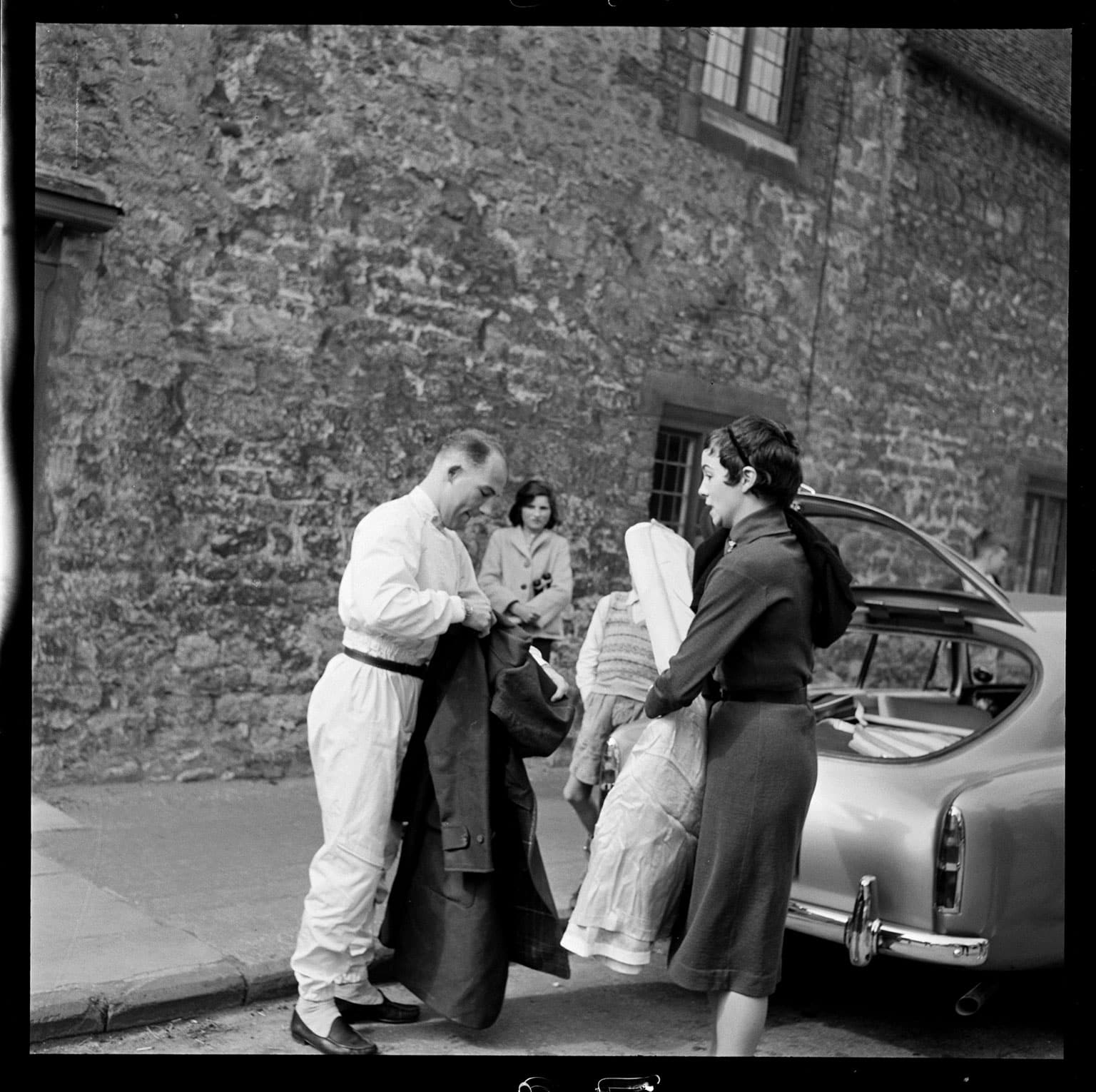

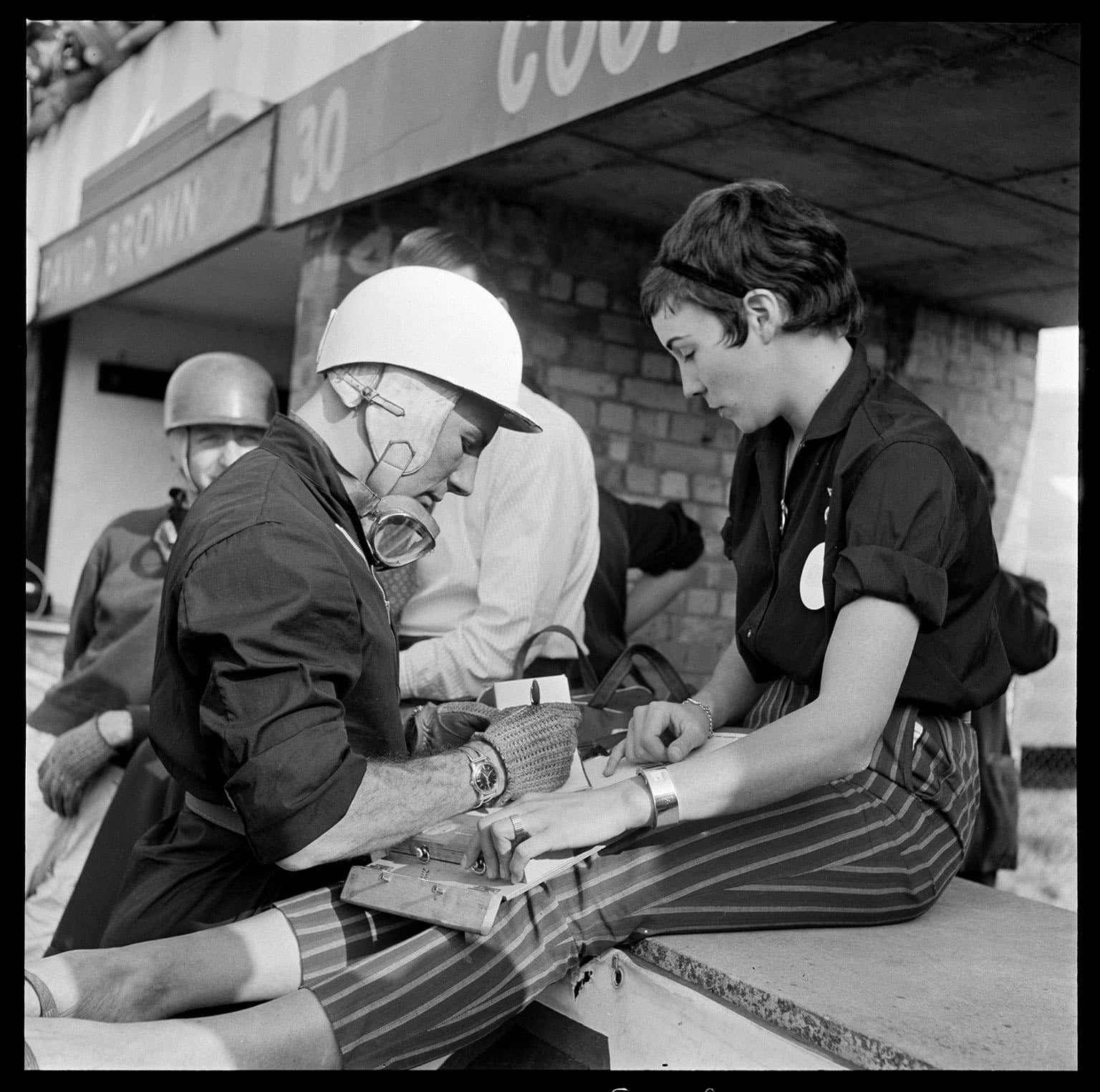

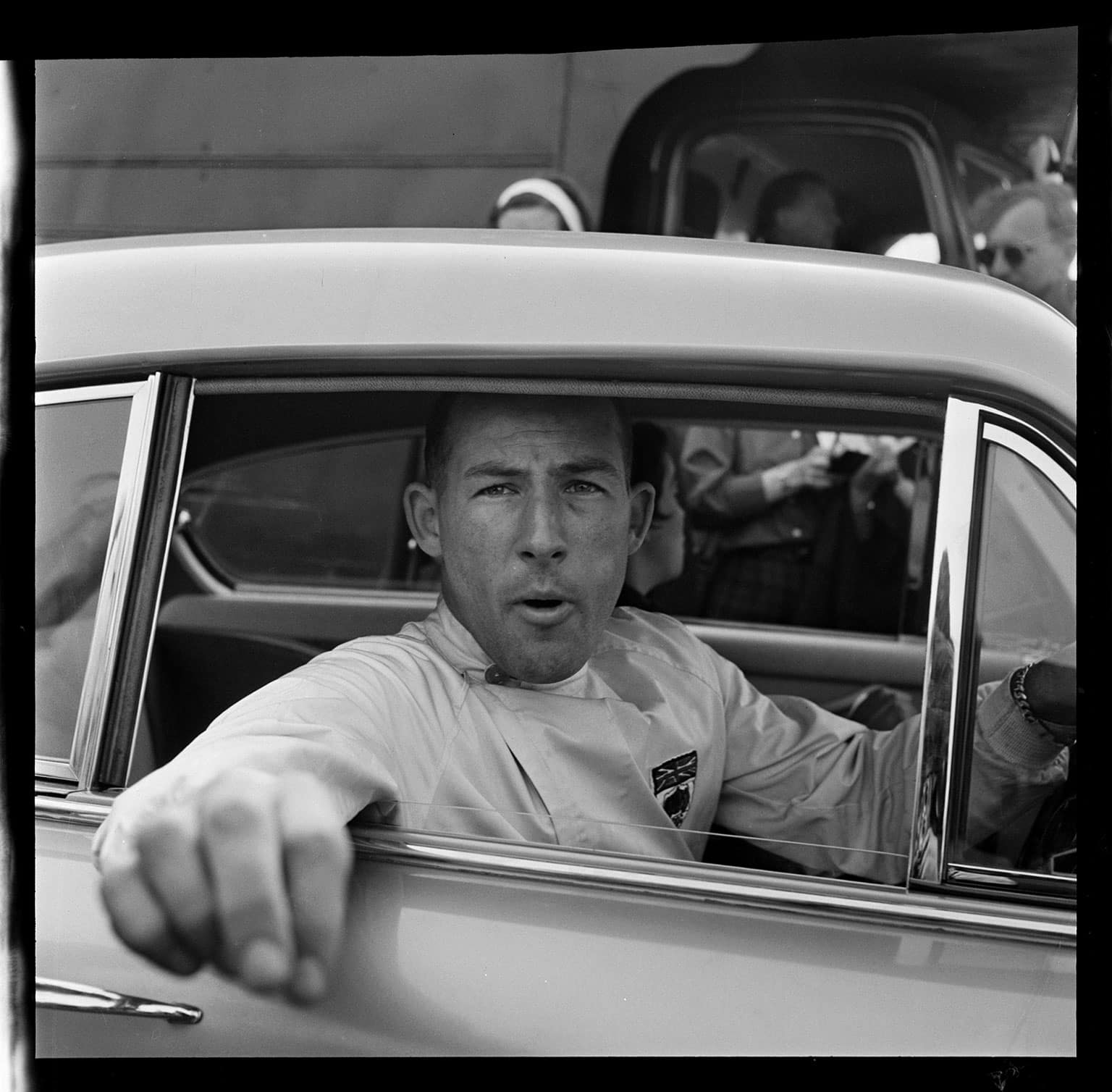

This collection of recently found photographs from the 1958 International Trophy at Silverstone give a fascinating insight into track life. From sipping tea while reading a magazine to signing autographs, rookie photographer Michael Ward was able to capture at close quarters a day in the life of a top racing driver

By the time he and his wife Katie set off for the circuit on the morning of May 3, 1958, he had won there in Cooper and Kieft 500s, in a Jaguar XK120, C-type and Maserati 300S sports cars, in a Jaguar Mark VII saloon, and in the Vanwall, which took him to a one-off victory in the 1956 International Trophy, a performance which persuaded him that here, finally, was a British-made F1 car capable of mounting a credible challenge to the continental teams.

He arrived at Silverstone for the 1958 International Trophy having already won the first grand prix of the season, in Buenos Aires. Not in the Vanwall, which was unavailable since its engine was still being converted to meet new regulations requiring the use of pump petrol rather than more exotic blends. Instead he had used Rob Walker’s little 2-litre Cooper-Climax T43 to outfox the more powerful Ferraris. Returning to the UK and with the Vanwall still not ready, he had raced the Cooper twice, retiring from the Glover Trophy at Goodwood and winning the Aintree 200.

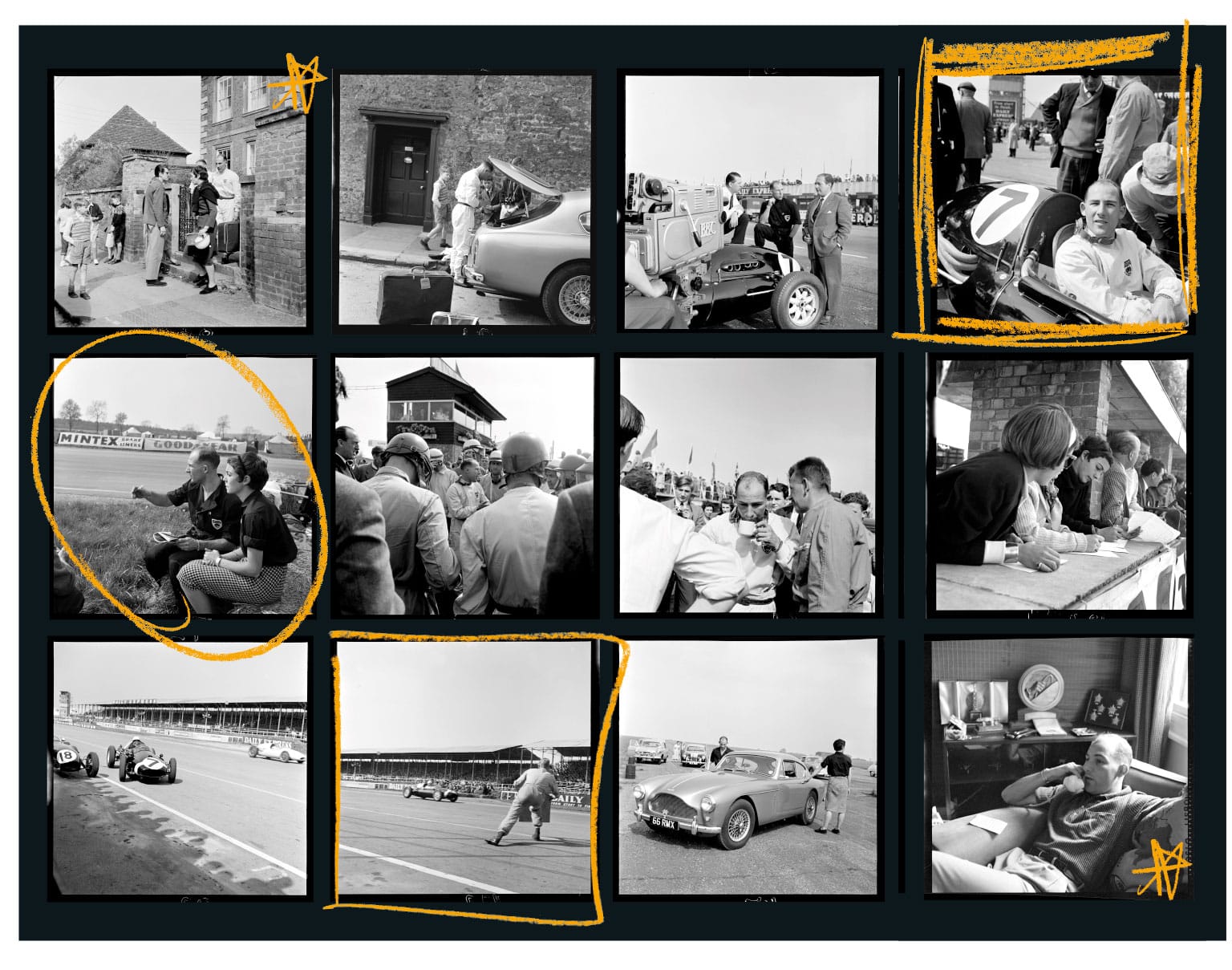

Moss, flanked by Jack Brabham and other drivers, listens to a briefing

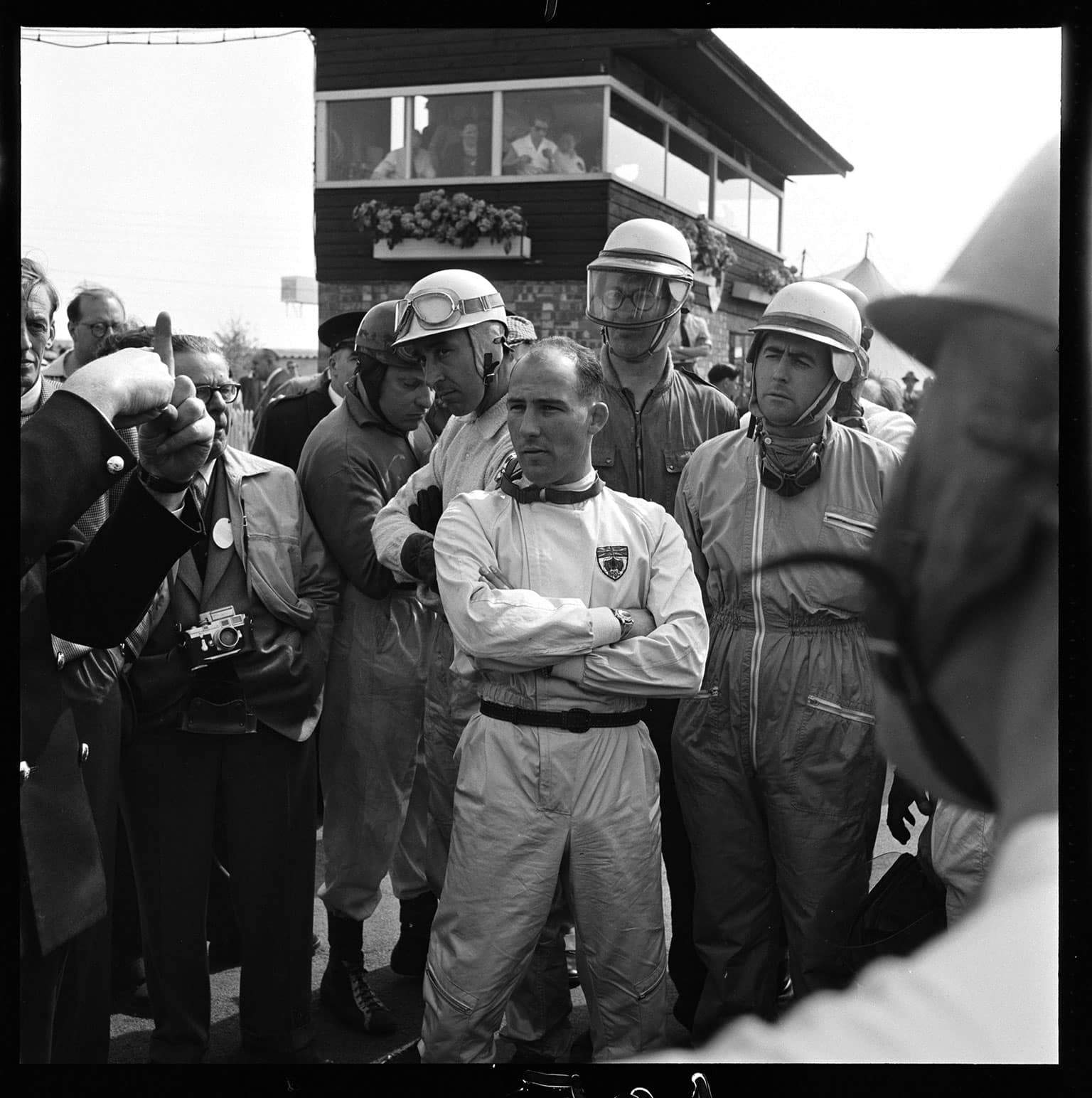

Packing, but with a difference: Nowadays you wouldn’t catch F1 stars rearranging the boot

For the International Trophy, the third in this little series of non-championship F1 races on British circuits, the entry list also included Peter Collins in the Scuderia Ferrari’s lone Dino 246, Jean Behra and Ron Flockhart in BRM P25s, Jack Brabham and Roy Salvadori in works Cooper T45s, Tony Brooks – his Vanwall team-mate – in a second Walker Cooper, and a flock of obsolete Maseratis whose drivers included Masten Gregory and Jo Bonnier. To fill out the weekend Moss also entered the accompanying sports car race in a works Aston Martin, a 3-litre DBR3, with Brooks in the team’s other entry, a 3.9-litre DBR2.

He and Katie, married in London seven months earlier, loaded their luggage into the back of an Aston Martin DB Mark III borrowed from the factory, stayed overnight near Silverstone, and were at the circuit in time for practice on the Friday, during which Moss put up the third-fastest time for the F1 race, completing the three-car front row alongside Salvadori and Brabham, with Collins and Behra behind them.

Moss’ first wife Katie was from the Molson beer-brewing family in Canada

Stirling and Katie arrived at Silverstone in style, in a works Aston Martin

The Mosses were accompanied throughout the weekend by Michael Ward, a young man who had just given up acting and was embarking on a career as a photographer. This was his first effort, and it was made possible only when Stirling, whom he knew slightly, lent him equipment. “He took me to lunch at the Steering Wheel Club in Mayfair and said that as long as I didn’t get in his way that was fine,” Ward said before his death in 2011. “As I was leaving, I remembered that I didn’t have a camera and I couldn’t afford the cost of hiring one. So I went back to the table and said, ‘There’s one snag – I’m afraid I don’t have a camera. May I borrow yours?’ He had a Rolleiflex 2.8. He smiled and said, ‘Yes but mind you look after it.’”

At the end of the meeting, Moss made a point of asking for it back. One shot, of Katie looking anxious on the pitwall, was published in Woman’s Own. The rest remained unseen. From this tentative beginning, Ward went on to a long and distinguished career as a Sunday Times news photographer, his assignments including the Troubles in Northern Ireland and the Aberfan disaster.

Moss shared driving duties with Tony Brooks in the Rob Walker Cooper-Climax T43

On the Saturday, Stirling arrived already kitted out in his white racing overalls. Katie had a sweater draped across her shoulders as a precaution against Silverstone’s spring climate. The weather stayed dry and not too cold, but the day proved disappointing. In the sports car race the Astons of Moss and Brooks were outpaced by the Lister-Jaguars of Archie Scott Brown and Masten Gregory and the Ferrari of Mike Hawthorn, and when Moss felt his engine tightening as he started to challenge for third place he pulled in and retired to prevent further damage. His fortunes were no better in the F1 race. Having stalled at the start, he gave the crowd a thrill as he battled back to fifth place when, just before half distance, his gearbox casing split, leaving Collins and Ferrari to claim the spoils.

This was far from the most memorable weekend of what was, even by Moss’ standards, an extraordinary year. In 1958 there were 20 wins from 40 races in 15 countries and eight makes of car. He had avoided a kidnap attempt by revolutionaries in Cuba, feared he was about to die when the steering of his Maserati broke at 165mph on the Monza banking, and saw out the year at a Hollywood party in the company of Tony Curtis, Steve McQueen and Joan Collins. With Fangio gone, he was now the world’s most famous racing driver. But he had lost the world championship by a single point, the result of a chivalrous gesture towards his greatest rival. It was the closest he would ever come.

Already in white overalls, Moss is photographed by Michael Ward – on one of his first assignments