Why Isle of Man TT is road racing’s great survivor

The Isle of Man is where British motor sport began: the first car races took place on the small island in the Irish Sea in 1904, the first motorcycle races…

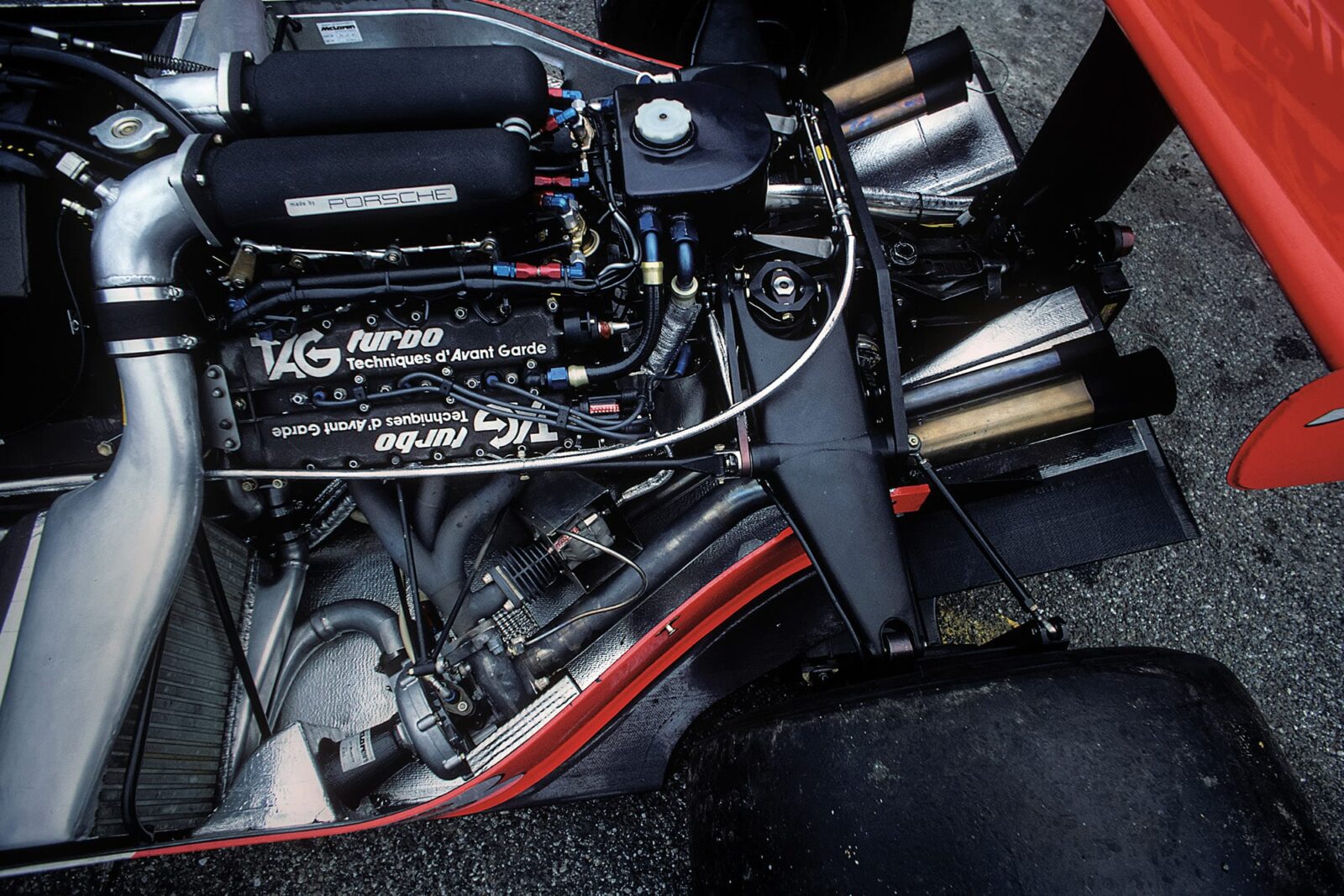

One of the 1.5-litre TAG-Porsche turbo V6s powered McLaren to a 1-2 in the ’84 Dutch GP

Getty

Having been rejected both due to a lack of experience and thanks to his former employment at McLaren during the early 1970s – and unsure as to which scenario was worse – John Barnard was sour as he sought a third bite at the cherry.

Seriously cheesed off at a lack of recognition for his groundbreaking ground- effect Champ Car, drawn up in his dad’s Wembley front room before it evolved into Johnny Rutherford’s 1980 Indianapolis 500 and Champ Car victor, Barnard did not want his Next Big Thing to be claimed by others or compromised by committee.

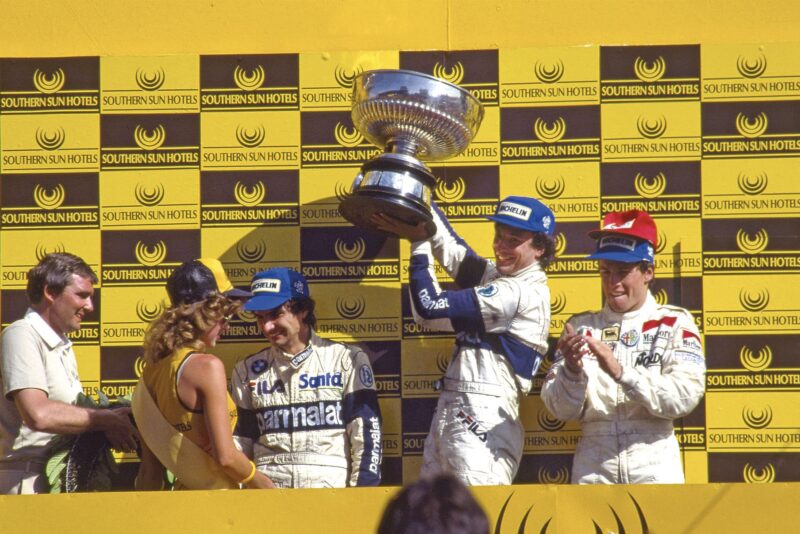

Brabham’s Piquet would win the world title at Las Vegas in ’81

DPPi

Thirtysomething and ambitious, he sought total authority on the technical front and equal billing elsewhere. So, he aligned instead with an ambitious junior formulae team boss, an ex-Formula 1 mechanic one year his junior, called Ron Dennis.

“I joined Project Four at the end of 1979 and started designing my first F1 car,” says Barnard. “Ron couldn’t get the budget to finish it, but John Hogan of Marlboro was very interested, and also very disappointed with how McLaren was going; it was he who would stitch the teams together.

“We upped their game. Everything that got made and done, how the car was put together, came from the drawing office – and I ran the drawing office. That put a lot of backs up. But McLaren had fallen off the technical bandwagon.”

Adjustments being made to Piquet’s Brabham at Monza in ’81

Grand Prix Photo

With their sharp eye for detail and far-sighted view of the bigger picture, Barnard’s design – the ‘carbon’ McLaren Marlboro Project 4/1 of 1981 – and practices, in conjunction with Dennis’s structures and systems, would become templates for F1’s mid-term future. In the shorter term, Dennis’s breezy confidence would have to whip and stoke Barnard’s fire within.

“F1 was aflame: Jean-Marie Balestre’s FISA versus Bernie Ecclestone’s FOCA”

F1, meanwhile, was aflame: Jean-Marie Balestre’s FISA versus Bernie Ecclestone’s FOCA; grandees versus garagisti; atmo versus turbo; English skirting of French rules lost in translation; Niki Lauda and more strident drivers; and TV rights for whatever was left standing. The first Concorde Agreement of 1981 just about kept a lid on things while a sometimes brattish Britpack scrabbled for more (horse)power: ‘Mr E’ with BMW; ‘Chunky’ Chapman and ‘Uncle Ken’ Tyrrell with Renault; and Frank Williams bonding with Honda. Tetchy relationships. Sketchy times.

Barnard reckons he got just 10 days’ notice for the rule change that would end the ground-effect era. And it was already November 1982. Three years’ work – with another scheduled – flushed down the tunnels in favour of flat-bottomed swirls without skirts. Gee, thanks.

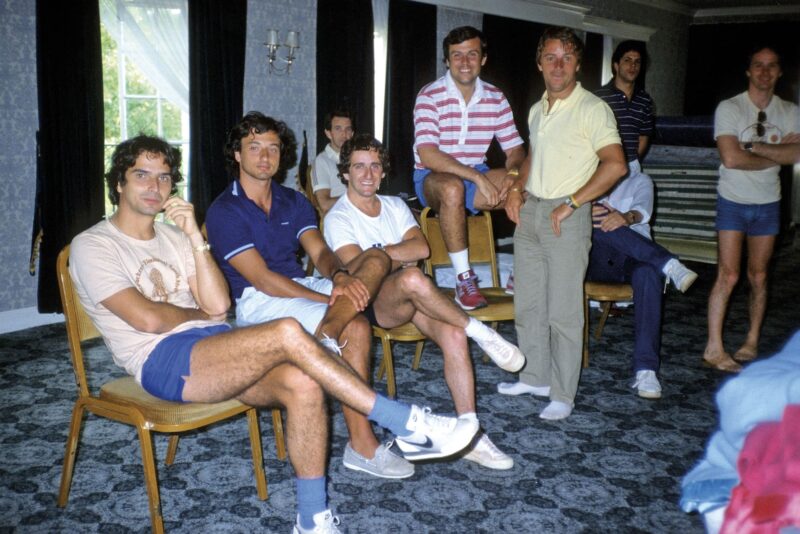

Drivers on strike at Kyalami in ’82

DPPI

And hadn’t he got the gig of total authority, plus his perfect turbo engine, because his former bosses had sucked at ground effect? Breezy confidence: Project Four. Breath of fresh air: McLaren International, end of 1980. Barricades stormed: the ‘Kings of Woking’, end of ’82. New broom. But now, kaboom! Shockwaves felt as ‘far afield’ as Chessington, home of Brabham. “I was worse off than most because Bernie was, shall we say, guiding the rules, and so I thought I had the inside line,” says the ostensibly more laidback Gordon Murray. “He kept saying: ‘Forget the rumours. We are keeping skirts.’

“I had the opposite philosophy to John Barnard. At Brabham, we always built our cars during the latter part of the season for the following year, then tested for about three weeks, usually in November, and thrashed the thing. BT51 – a small-tank ‘pitstop’ car – was testing around August-September; plus, we had another two virtually built. I’d given myself so much time because also we were having to design and develop tyre warmers and high-pressure refuelling – they took almost as long as the design of the car itself! – as well as practice pitstops.

Brabham shone in ’83 at Kyalami, with Andrea de Cesaris winning and Nelson Piquet in third

DPPI

“Then: no skirts! Everything on BT51 – centres of gravity and pressure – was in the wrong place now. For the first time, I was absolutely on the back foot. With no time to do anything other than theorising. And that theory was a sketch: this is what’s going to happen. I dumped the sidepods and moved the centre of gravity rearwards by seven per cent. That’s huge, a gut-feel. We didn’t start until November, and it was absolutely day and night after that. There were probably only around 40 of us; the design staff was me and David North. We kept it clean and simple with very little adjustment. That was because of time constraints, but also because I knew the year was going to be all about turbo engine development.

“Ill fate, judgement and tempers stripped F1 of its veneer of innocence in 1982”

“I thought everybody would be doing the same. When we arrived in Rio, [in March 1983 for the season opener], I realised we were out on a limb. I felt confident still. I don’t know why. It was a big risk – even forgetting pitstops – to move that much weight around and turn up without testing. I wouldn’t have been that radical given a bit more time. We would have had short sidepods to generate some downforce.” This was the ‘mature’ tactical world in which nascent Marlboro McLaren International was attempting to operate as a strategic entity. It rejected accepted conventions, including folded aluminium tubs, and a turbocharged engine reckoned “good enough for Lotus”.

“Our thinking was that we could do better,” says Barnard – who had placed it on a collision course and under heavy scrutiny.McLaren had survived 1981 – witness John Watson’s crash at Monza’s second Lesmo and team-mate Andrea de ‘Crasheris’ having incidents at many other places. Despite still sharing power with the old guard, it provided a relative oasis of calm resolve during 1982, as ill fate, judgement and tempers stripped F1 of its veneer of innocence: the deaths of slighted, angry Gilles Villeneuve and poor, unsighted Riccardo Paletti; rules openly flouted and ‘in the spirit’ airily touted; Lauda’s red-and-white ‘Kyalami army’ and ‘Me or Imola’ teams both out on strike. How was a man supposed to think, especially when the dark year led to regulation changes to improve safety? And yet.

F1’s 1983 season opened in Rio unpredictably due to late rule changes. Brabham’s Piquet won

Getty

“Everything about the design, manufacture and construction of MP4 was of a magnitude I’d never seen before,” says Watson, who had joined McLaren from Brabham in 1979. “Accuracy; repeatability; and none of the inconsistencies of the old methods. John virtually had carte blanche and went to America to get the technology. His uprights and the like were thus lighter, stronger and shedloads more expensive.”

That, however, was before 1984’s proposed regulations had been brought forward 12 months. The clocks were striking 13, as George Orwell once wrote.

“Having picked myself up off the floor,” says Barnard of his sudden ground effect ban design dilemma for 1983. “The first thing I did was go back to the wind tunnel models; having separate body panels gave us greater flexibility aerodynamically: delta-wing cars; long, thin cars; all sorts. Basically, I took areas from a couple, put them together and came up with the ‘Coke bottle’ shape. That proved quite effective at recovering some of the downforce lost and set a trend.

Lauda ahead of the ’84 Portuguese GP in which he would secure the drivers’ title

Getty

“Had I known, I would have changed the turbo engine’s specification [to better suit a flat-bottomed car], but I had underestimated the value of a purpose-built unit. Ours was a fully stressed member. Compact, too. Factors that allowed me to do aero that others couldn’t.

“Nobody else but Dennis would have tried to sign Senna alongside Prost, never mind make it happen”

“Ron gave us the ability to do all that stuff – the [bespoke] TAG-Porsche turbo; a wind tunnel with a rolling road that gave usa better understanding than our rivals – because he did the deals that Teddy couldn’t.” Dennis had also put in the cold call to Stuttgart that [former outright McLaren boss] Mayer was cool on.

Not that Barnard had his ‘perfect’ engine yet. For a man reputedly running a short fuse, he favoured the slow burn: an immaculate conception; a long gestation; newborn preparedness. Design long and hard; build late and decisively – unless railroaded by a driver with clout.

Lauda (McLaren) and Senna (Toleman) go head-to-head at Dallas in ’84

Grand Prix Photo

An impatient Lauda – another unlikely deal pulled off spectacularly by Dennis – went directly to Marlboro to shout the odds: “‘Listen, if this turbo car does not start in 1983, you’re not going to win in ’84’. Ron and John were upset like you wouldn’t believe.” Barnard would later admit that important lessons were learned with the resultant troublesome MP4/1E hybrid that so offended his perfectionist sensibilities. “It was my decision to bring it early,” continued Lauda in To Hell and Back. “But the rest, the team did; Barnard did. The engine was perfect: horsepower, driveability. You needed a big rear wing which Barnard did not agree with in the beginning. But it was the best car.”

‘Coke Bottle’ MP4/2 won 12 of the 16 races in 1984 as the team romped to the constructors’ prize and Lauda pipped returning team-mate Alain Prost to the World Championship by a half-point. Yet Barnard was hardly turning cartwheels.

“Come August, when we knew we had the championship won, my brain turned to the next year: ‘Christ! I’ve got to do it all again’. By the end of 1984 – I’m not entirely sure why – I wanted to sell my shares [up to 43 per cent from the pre-takeover nine]. Ron and I had put our houses on the line to get the loan to do the deal. A big commitment. I was married and had two children and didn’t like taking financial chances. So Ron did a deal on my shares with Mansour Ojjeh of TAG.

Elio de Angelis retired in the ’86 Monaco GP due to a turbo problem

Getty

“I found it very draining. As you move up, the pressure increases and the enjoyment decreases. But you shouldn’t go into F1 unless you have the character to say, ‘I’ve got to win. Take that next step. Move things on’.”

Barnard, with a workforce of just 75 – “including the tea lady” – contented himself with evolution on this occasion. He’d earned the right because of the rightness of his original: there had been very few modifications in 1984, with Lauda driving the same chassis in every race. An ageing Formula 2-based gearbox remained a worry, but MP4/2B would prove good enough in 1985 with another constructors’ and a first world title for Prost.

MP4/2C of 1986 was good enough too, just. For an inspired Prost, at least. New team-mate Keke Rosberg couldn’t handle its understeering stance, about which Barnard, by now just an increasingly disaffected employee, was disinclined to do anything. He knew that the MP4/2s were done with and so was working on his next Next Big Thing – for Ferrari, albeit strictly on his terms in Guildford, in a building that is today occupied by the Gordon Murray Design company.

Alain Prost and Gilles Villeneuve ahead of the ’81 Monaco GP; the latter would win the race

Getty

Dennis, too, knew that change was due. His team had grown too big, too quickly – 150 staff by 1988 – for one man to rule its technical roost. His simplistic simpatico arrangement with Barnard and McLaren’s customer relationship with Porsche – had been ideal for a burgeoning kingdom but was unsuited to the expansion and upkeep of an empire. Now he wanted an exclusive long-term partnership with a manufacturer – and to sign the world’s two best drivers. For 1988, he peeled Honda from Williams a year early, even though Barnard had left in August 1986, and persuaded Senna – interwoven processes – to sign even though Prost had his feet under the table. Imagine the convolution. Nobody else would have tried it, never mind make it happen and, for a briefly glorious time, work. That brand image was armour-plated now. But frailties lay beneath, as reluctant convert Murray had discovered.

“Now a business with sport attached, the new F1 was growing exponentially”

“I was stopping F1,” he says. “I’d had enough of the travel and living out of a suitcase. I’d won 20-odd races and two World Championships [including 1983 with Nelson Piquet]. Was I going to beat myself up to win another couple? Plus, Bernie had lost interest in the team. He’d used it as a springboard to run F1 – and done a brilliant job of doing so. He’d let Nelson go. To cap it all, we had lost Elio [de Angelis to a survivable testing accident at a Paul Ricard test in May 1986]. I wanted a change: Le Mans or a [road-going] sports car.

Mansell (Williams) on the way to victory in Austria, but he would ultimately miss out on the ’87 title

Grand Prix Photo

“But then John Barnard went to Ferrari and Ron was looking for somebody for technical director at McLaren. He said that all he was interested in was winning championships. I took a lot of persuading before I agreed – to just three years. That would be my 20th. I told him that nothing would persuade me to stay in Formula 1after that.

“They had some good guys at McLaren; I got rid of the bad ones very quickly. They had a very good manufacturing element, too. What they didn’t have were systems for reliability. Brabham was a small team, yet we had life-ing systems in place, a torsional testing facility and a transmission rig to study oil flow. We’d had technical meeting rooms, too, and kept massively detailed records of every failure.” A very early computer system would then dump any duff stuff from the stores before the next race.

“When I asked how John had downloaded the good and bad after each race, I was told that he kept everything in his head. They didn’t video pitstops. They didn’t have an autoclave. That was my biggest shock. I said to Ron, ‘I’m sorry, I know you’ve just finished this new building and that its composite shop is nice and clean and shiny, but this is ridiculous.’ We’d had an autoclave at Brabham since 1978. I thought I’d be bringing design flair and hopefully a bit of leadership. What I had to do was go back to basics and get all these systems in place. Design was less than 50 per cent.”

Ferrari took a famous 1-2 at Monza in ’88 to honour the late Enzo after his passing earlier that year

DPPI

Autoclave installed; computerisation approaching completion; reliability pretty much rock-solid by 1988: the team came within two laps of Monza – and impatience from Senna and indecision from rookie Jean-Louis Schlesser – from completing a clean sweep of victories: 16 from 16.

“That season had parallels with 1983,” says Murray. “MP4/4 [overseen by a team led by Steve Nichols] was built at short notice [the Honda deal had been announced the previous September] and kept simple: body, aero and suspension not terribly fancy. But it had a radical transmission – the first dry-sump gearbox – tested once. That could have gone wrong all season. But it didn’t.

“What goes wrong during a season like that is morale. People get complacent, expect to win, and stop working properly. After every race, I’d go around the factory and give everybody [increasingly more of whom were nine-to-fivers with no motor sport DNA] a pep talk.

McLaren in a league of its own, winning 15 of 16 races in ’88.

Getty

“And I loved working with Senna and Prost. I even liked sorting the problems they caused; we had to have pretty strict rules. It would have been nice to win them all.”

Barnard then Murray; Lauda and Prost and then Senna; Porsche then Honda; and Marlboro throughout: a superteam that had raised the stakes – and driven one through the quavering heart of old F1.

Now a business with sport attached, the new F1 was growing exponentially: from out of the Piranha Pool, to the Land of the Dynasties.

1980 Alan Jones secures Williams’ first F1 title against the background of the FISA vs FOCA power struggle. FISA teams – Ferrari, Renault, Alfa Romeo – withdraw from Spanish GP. The race is stripped of its championship status.

1981 Ferrari joins Renault in the turbo ranks. Nelson Piquet takes title in naturally aspirated Brabham-Cosworth.

1982 Ferrari is favourite, but loses Gilles Villeneuve (killed in Belgium practice) and Didier Pironi (badly injured in Germany warm-up). Eleven drivers and seven teams win. Keke Rosberg becomes the last DFV-powered champion.

1983 Piquet takes his second title in three years, this time with BMW turbo power.

1984 Refuelling banned. Closest fight of all, mathematically, as Lauda beats McLaren team-mate Alain Prost by half a point.

1985 Prost secures his maiden title in the GP of Europe at Brands Hatch. Martin Brundle becomes the last driver entered for a GP with Cosworth DFV power, but his Tyrrell fails to qualify in Austria.

1986 Nigel Mansell is on course to become champion until his Williams suffers a blown left-rear tyre in Adelaide. Prost picks up the pieces. All cars run turbo engines.

1987 Mansell wins six GPs to Williams team-mate Piquet’s three, but consistency rewards Piquet. Naturally aspirated (3.5-litre) engines return and drivers thus equipped compete for the Jim Clark Cup, won by Jonathan Palmer (Tyrrell).

1988 McLaren wins 15 of 16 GPs in final season before turbos are banned. It would have been 16 had champion Ayrton Senna not tripped over Williams stand-in Jean-Louis Schlesser at Monza. That gifts victory to Ferrari driver Gerhard Berger, a few weeks after the team founder’s death.

1989 A simmering McLaren feud boils over. Team-mates Prost and Senna clash at Suzuka and the Brazilian’s subsequent exclusion, for rejoining the circuit ‘incorrectly’, settles the title outcome in the Frenchman’s favour.