2022 BMW M240i review: Get the show on the road

You can spin the story of this car in two quite different ways. The easily pleased will point to the fact that here is an ‘M-performance’ 2 Series with near…

Mercedes leads Red Bull in Singapore 2013, a sign of things to come

It was the decade of domination. Never had Formula 1 been so one-sided. At the same time, it was the decade in which F1 turned its relationship with the world around by 180 degrees. The two facts are probably not unrelated.

Only two teams won World Championships in the 2010s – Red Bull and Mercedes. It’s hardly a secret, but seeing it written down is shocking, nonetheless. And two drivers shared 90 per cent of the titles between them in Lewis Hamilton and Sebastian Vettel. The interloper was Nico Rosberg, who shouldn’t really have won in 2016, but was effectively gifted his championship by the worse reliability of team-mate Hamilton’s Mercedes.

This concentration of power to an unprecedented degree had a series of effects. For one, it distorted the statistics of the decade and arguably made one driver – Vettel – appear better than he really was, judging by subsequent events. It drove the other defining driver of the decade, Fernando Alonso, to desperate decisions seeking the success that domination by others prevented. He would ultimately exit F1 with just the two titles.

Nico Rosberg defeated Lewis Hamilton in 2016…

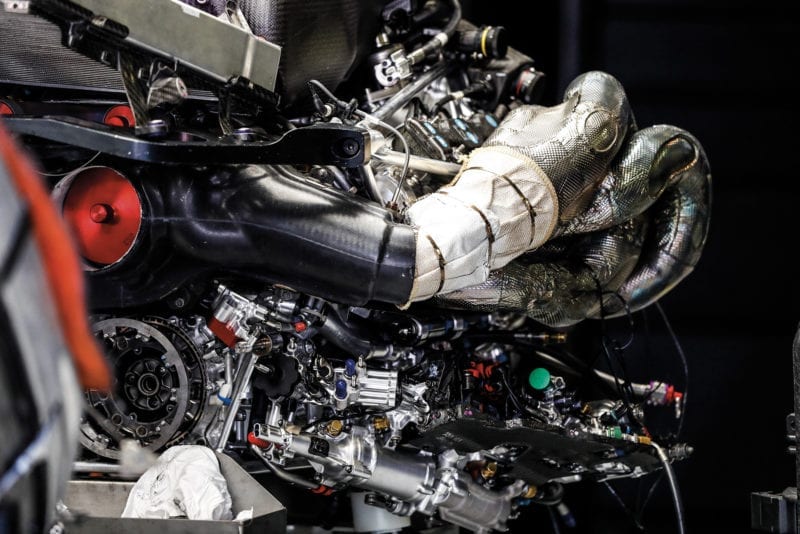

… as Mercedes dominated the expensive hybrid engine era

Simultaneously with these results was a navel-gazing of the like F1 has probably never seen before – and nervousness about the state of it that created an increasing focus from its participants on trying to ‘fix’ F1.

The causes of all this can at least in part be traced to Bernie Ecclestone, who had overseen the previous three decades of F1. By the end of this one, Ecclestone was cast aside. New owners, who undertook a revolution in F1’s management, did the deed, but the sense Bernie was out of time was prevailing long before that.

On-track, the 2010s started with the abandonment of refuelling, on grounds of cost and the fact it was destroying racing. It was the first of many decisions made in the 2010s that were aimed at improving the ‘show’, born of a sensitivity that it wasn’t good enough.

“Ecclestone’s move backfired, granting significant control and influence to Mercedes and Ferrari”

Off-track, the decade began with a low- key war. The teams unified under their umbrella group FOTA (Formula One Teams Association), emboldened by forcing out Max Mosley as FIA president the previous year in a fight to kill off a punishing cost cap. The outfits were determined to defend themselves from Ecclestone’s capricious ways. Ecclestone, in turn, was hell-bent on heading off this new threat to his power base.

In breaking up the teams’ unity by using a combination, as ever, of money and menace, Ecclestone thought he was creating a new governance structure that would guarantee him greater authority than ever before. But his system backfired, and instead granted significant control and influence to the teams, or two in particular: Mercedes and Fiat/Ferrari.

That authority accidentally invested in F1’s two most prominent organisations ensured that a forward-looking decision at the start of the decade to introduce hybrid engines could not be reversed, however much Ecclestone railed against it. Ironically, hybrids were a move initiated by Mosley, a long-time Ecclestone ally.

Ecclestone exited F1 in 2017. Chase Carey, right, is the new CEO

And that hybrid push led in time to F1’s rush towards the future, towards a new attitude and a new relationship with the world. A determination to be a responsible contributor to it, rather than a rebel force, could no longer be stopped.

Ecclestone broke up FOTA in 2011 by offering Red Bull a new prize money deal that was too good to turn down. Once Red Bull had broken away, it was easier to get Ferrari to do the same – by offering it an even better deal than the one given to Red Bull.

The others quickly followed. Only McLaren had stood firm, but that was until Ecclestone threatened to ditch the Bahrain Grand Prix unless the team’s owners – the Arab country’s royal family, whose race it was – overruled its team principal Martin Whitmarsh and ordered him to sign up to the new contract. These new prize money structures offered some teams an extra revenue stream above and beyond those available to the rest. In Ferrari’s case, this amounted to more than an extra $100m (£77m) a year, a combination of the ‘constructors’ championship bonus’, also given to Red Bull and McLaren, and a separate payment for being a ‘long- standing team’.

Sebastian Vettel celebrates his first of four titles in ’10

For Red Bull and McLaren, it was worth over an extra $30m (£23m). Mercedes had begun the decade as a new team owner, having bought out the 2009 championship- winning Brawn team, but Mercedes struggled to make a success of it because of dramatic cuts made before the manufacturer took over. Mercedes negotiated a contract which stated it would also secure the CCB if it won two consecutive championships. With the advent of hybrid engines in 2014, that did not take long to arrive.

This extra money shored up the budgets of teams that were already better funded than the rest thanks to their owners’ financial security and willingness to spend. And it did so at a time when the development of technology, and the complexity of how cars had to be designed and operated, was becoming exponentially more responsive to resource. Extra money meant more staff, more hours devoted to the research of the airflow structures around the car, more stable aerodynamics, more consistent downforce and, ultimately, a faster lap time.

By the end of the decade, the best cars did not necessarily have more total downforce than those in the upper midfield. But they certainly had a lot more downforce a lot more of the time. The extra research ensured they could guarantee a stable platform through more car states – pitch, yaw, corner entry, mid-corner, brake-throttle transition, bumps etc. That led to a performance chasm between the top three teams and the rest, who were often lapped by the end of the race.

Adrian Newey’s ’09 RB5 set the template for F1 cars in the 2010s.

In Red Bull’s case at the start of the decade, design head Adrian Newey, in concert with engine partner Renault, found a new way to use exhaust gases to increase rear downforce, a technique known as an exhaust-blown diffuser. In addition to a specific bodywork design at the rear of the car, this required careful control of engine mapping to ensure the right level of gas flow. No-one else was able to match Red Bull and Renault in this field.

That gave Vettel a car that was effectively unbeatable for four seasons, while Hamilton and Alonso were always fighting a losing battle in machinery that was sometimes competitive enough to allow them to beat him, but not consistently enough.

Alonso got closest and would have won the title twice had it not been for awful luck. In 2010 Vettel and Red Bull were still making mistakes, and in 2012 a change to the rules meant that it took half a season for Newey and Renault to get their exhaust-blowing working properly again. Alonso produced the season of his life, and one of the greatest by anyone ever.

Fernando Alonso had two title near-misses at Ferrari before his disastrous ’15 McLaren switch

But Alonso could see the way things were going and concluded that he had to get out of Ferrari at the end of 2014 because he couldn’t envisage Ferrari ever matching the aerodynamic excellence of the leading British teams.

The decision – and the route he took in joining a McLaren team in a state of denial at how far it had fallen – effectively ended his career.

At McLaren, Hamilton made the same decision as Alonso a year earlier. But, unlike his old team-mate’s move, Hamilton’s was the making of him. Hamilton’s timing – fortuitous, to at least some degree – was to leave one team just as it was beginning a precipitous decline and joining another just as it was about to begin a period of record- breaking superiority.

Fernando Alonso’s huge Australia crash, during the nadir of his F1 career

Frustrated by several things at McLaren, Hamilton chose to believe the romances of Mercedes and the arguments it made to him that it was better placed for the looming hybrid era than anyone else. So, Hamilton jumped ship for 2013. At the time, he had won 11 fewer races than Alonso. By the end of the decade, Hamilton had added a further 63.

The hybrid engines came to F1, much to Ecclestone’s chagrin, because Mosley and his successor Jean Todt recognised that F1 could no longer ignore the direction in which the world was travelling.

“The turbo-hybrid engines meant that only players with huge budgets could compete in F1.”

With climate change now an increasing global concern, the FIA realised that, sooner or later, pounding around race tracks burning fossil fuels for fun using outdated, large-capacity, normally-aspirated engines, would make F1 a target. F1, it concluded, had to justify its place in the world and make an argument for its continued existence. The engines were the answer.

As Mercedes boss Toto Wolff puts it now: “These things need to be tackled, and when we look into our micro-cosmos, these engines have all the energy recovery that you can find in the most modern road cars. We have battery technology, we have energy recovery, through various systems, and they have become more and more efficient. They are very much at the forefront of technology that eventually ends up in road cars.

“Each of us has a duty, be it in our little small world, of not using plastic bottles any more or looking after our own environment. In the same way as the guys involved in Formula 1 – making sure the right message is transported into the world, that these engines are the most efficient and the most green engines that have ever existed.”

Jumping for five: Hamilton’s Singapore victory sends him closer to another title

The technology chosen was complex and expensive. The engines were implemented to dramatically increase the thermal efficiency of the internal combustion engine, hoping the advances would translate to road cars, but it meant that only players with huge budgets could compete in F1.

Mercedes recognised the possibilities sooner than anyone else and committed more resource to it earlier. The result was a dramatic performance advantage when the engines first appeared in 2014, a figure its rivals believed was close to 80bhp.

Ecclestone never liked the hybrids and did his best to denigrate them from the beginning. The result was that rather than trumpeting the revolutionary technical achievements of the engines, which increased thermal efficiency from around 30 per cent to 50 per cent, and talking about how much that would reduce carbon emissions if it could be translated to road cars, F1 found itself in a fundamentally irrelevant controversy about their sound.

For a time Ecclestone even led a bid to reintroduce the V8s that had been abandoned in 2013, but the manufacturers could see wider industry trends and stood firm.

The old impresario’s last ‘hurrah’ was a disastrous change to the qualifying format at the start of 2016, which was quickly reversed. Within a year, Ecclestone was gone, and with him went a way of doing business.

After several false dawns, Ferrari has yet to hit back against Merc

For decades, Ecclestone had moved from deal to deal, his sole target to make as much money as possible while expanding F1 in whatever direction the dollars led him. Tactically, he was a master and strategy hardly came into it. He made a lot of money – for himself, and for the people who from 2006 were his masters in the form of a private equity group. Very little thought was given on a macro level as to what F1 should be, let alone what it should be in five or 10 years.

When F1 was bought by the US group Liberty Media over several months leading up to the start of 2017, all that changed. Suddenly, the talk was business plans, marketing, expansion into the digital realm, and exploiting the possibilities of the internet, an entity Ecclestone admitted to not understanding.

Ecclestone, a former used-car dealer, was replaced at the helm of F1 by Chase Carey, an Ivy League-educated businessman and television executive. In the three years since, seismic changes have been made in F1.

Liberty has a plan to expand F1’s footprint in the US, further into Asia and, ideally, into Africa also. The calendar is growing, Vietnam had been added before its cancellation due to the coronavirus pandemic. Changes are being made to race weekends to lighten the load on those involved.

Will the next era belong to Red Bull and Verstappen?

A cost cap–oh the irony–has been introduced for 2021, to reduce the ever- widening gulf between the big teams and the rest, and a new, more equitable prize-money structure and streamlined governance process, less prone to logjam than the one Ecclestone set up at the start of the decade, are on the verge of being agreed.

While Ecclestone largely ran F1 as a one-man band, Liberty has recruited extensively, among the additions a team of engineers charged with researching future rules, under the leadership of former team boss Ross Brawn. The first fruits of that work will be seen in 2021 when new regulations are introduced. It’s hoped it will not only close the field in terms of competitiveness but also make the cars more raceable. Beyond that, there is a vision for how F1 must represent itself to the world if it is to survive.

The 2020 season was set to start in Australia, in the shadow of the apocalyptic bush fires of the last few months, their severity fuelled by climate change and the record temperatures seen in Australia in recent years.

If that race had gone ahead, the optics of F1 going to Melbourne and driving extravagantly fast, petrol-powered cars around in circles for three days would not have been good. A decade ago, the issue would have been ignored. Now, F1 is not only actively working to support victims of the fires, but it can also point to a plan to go carbon-neutral by 2030 as evidence F1 is now a responsible global citizen, rather than a profligate and irresponsible playground for rich men and their irrelevant toys.

There is a desire to use F1 to showcase how the car industry can help reduce carbon emissions. The aim for the next engine regulations in 2025 is to retain hybrids and lead the introduction of synthetic fuels, the manufacture of which will capture carbon from the atmosphere and combine it with hydrogen, the use of which would be carbon-neutral.

Renault F1 boss Cyril Abiteboul says: “We are talking about e-fuel, fuel that will not be composed of fossil energy. This will be a game-changer, I think. We need to make sure that Formula 1 remains a demonstration for game-changers.”

Carey adds: “Electric is going to be part of the solution, but they have their own issues, whether it’s economics or batteries or what have you.

“We have a billion-plus cars out there today with combustion engines. We are a platform for showing what a hybrid engine can be, in terms of playing what is a critical and underappreciated role, that is necessary to address the world’s larger environmental issues. For us, this is an offensive issue, not a defensive issue. We have a capability and opportunity to play a leadership role and develop a path forward to the goals we have set out.”

Imagining those words coming out of the mouth of Carey’s predecessor is impossible. There is no more effective illustration of how, in the space of 10 years, F1 is not only operating within a changed world, but is one itself.

Andrew Benson is BBC Sport’s chief F1 writer

2010 Points revised: 25-18-15-12-10-8-6-4- 2-1. Refuelling banned again. Showdown in Abu Dhabi between Fernando Alonso, Lewis Hamilton and Red Bull’s Sebastian Vettel and Mark Webber. Webber gambles and Ferrari covers the move, allowing Vettel to steal the title.

2011 Pirelli replaces Bridgestone. Vettel wins in Australia – and this time stays ahead all season.

2012 The first seven GPs produce as many different winners, but it’s Vettel vs Alonso. Vettel recovers in Brazil to triumph.

2013 Vettel leads the standings at the mid-summer break, then wins the next nine races to seal another title.

2014 Hybrid V6 turbos introduced, double points given at Abu Dhabi. Mercedes dominates and Hamilton takes the title. Double points dropped. Jules Bianchi suffers serious injuries during the Japanese GP, later becomes first WCGP fatality since Senna.

2015 Vettel wins three times for new employer Ferrari, but Mercedes takes the other 16 victories and Hamilton (responsible for 10 of those) is champion for a third time. Max Verstappen becomes the youngest F1 race starter, aged 17.

2016 A contest in which psychology plays as great a part as performance. Nico Rosberg beats team-mate Hamilton… then retires. Verstappen wins on his debut for Red Bull in Spain, aged 18.

2017 Quite a competitive campaign, by the standards of the hybrid era: Mercedes wins ‘only’ 12 of 20 GPs as Hamilton adds another title to his CV.

2018 It takes Hamilton four attempts to notch his first success in a 21-race season, but another 10 then follow. Five down…

2019 Bonus point for fastest lap returns (if the driver finishes in the top 10). Valtteri Bottas dominates Australian opener to trigger talk of a serious challenge to Hamilton, but this never materialises. The Englishman goes into 2020 looking to equal Schumacher’s seven-title haul.