Book Reviews, September 1948, September 1948

": PRIVATE OWN I.: It by L. R. Higgins (Foulis, 8s. 6d.) This is a long-awaited 176-page book about motor-cycle racing, seen from the saddle by an amateur rider and…

Fourth title: the iconic sight of Schumacher celebrations, here after victory in Hungary in 2001

Clive Mason/Allsport

It was Michael Schumacher at his peak for the first few years of the new millennium, rattling off World Championship titles as if it was child’s play. All previous markers of achievement were obliterated as the German unleashed his gift, supported by the most brilliant group of individual talents ever assembled in Formula 1, with vast resources at their disposal. Even the combined might of McLaren, Mercedes, Adrian Newey and Mika Häkkinen wasn’t enough to deny Ferrari and Schumacher.

Häkkinen, the only Schumacher contemporary of comparable talent, had retired exhausted at the end of 2001, making Ferrari’s task easier. Williams and BMW together then offered some competition, but it was a flawed partnership. The Schumacher/Todt/Brawn/Byrne superteam, and their mutual pact to keep senior management from disturbing the equilibrium, meant Ferrari’s results were finally matching its spend. It could always justify the expense, and it was up to the rest to catch up.

Which they set about doing. This was F1 in full commercial flow as it rode a tsunami of investment from automotive companies. Their money spread like wildfire and teams scaled up into altogether bigger and more serious entities, with 800-plus employees and £200m budgets at the top outfits. But like a wildfire, growth was difficult to contain. So F1 gorged itself on arms race developments in engines, wind tunnels, computing power and tyre wars. US President Bill Clinton lifted the post-1930s banking restrictions in the 1990s and opened the global economy’s casino. Everyone was spending. So F1 expanded like a balloon that was always going to go pop – which it duly did, near the decade’s end.

Michael Schumacher leads Ferrari team-mate Rubens Barrichello at Monaco in 2004

But hell, that was tomorrow. No point pondering about such things when there was always more to be had today. F1, like the world itself, would simply consume whatever was available and the day of reckoning be damned. The white noise of V10s drowned out any questions about the future of massively expanded teams when the bubble burst.

“F1’s magnificence was because of pure uninhibited, addicted, indulgence of speed”

Lap times were sliced even as the FIA tried to contain performance. Those 3-litre V10s were nudging ever-closer to 1000 horsepower by the time they were outlawed and replaced by 2.4-litre V8s of a more prescriptive spec for 2006. Yet still the lap times fell, despite the loss of 200bhp. Tyre compounds were evolving at a breakneck pace. At Interlagos, the 2005 backmarker Minardi, unaltered from the year before, could lap faster than Schumacher’s dominant 2004 Ferrari had done! That was tyre development, nothing more.

Bridgestone and Michelin went at it, hundreds of boffins armed with mutating software that seemed to make the laws of physics as bendy as a Michelin sidewall. At Ferrari, Mercedes, BMW, Renault, Honda, Toyota and Cosworth, dynos were coaxing the tiny sub-100kg motors towards 21,000rpm, each extra increment of engine speed gained at a cost of millions. At the same time, one- tenth of aero performance found in the wind tunnel was reckoned to cost around £1m.

But what was this arms race science for? Nothing. It was just to make the cars go ever- faster. F1’s magnificence was because of pure uninhibited, addicted indulgence.

Mosley and Ecclestone at the height of their powers in ’06

Commercial rights holder Bernie Ecclestone and FIA president Max Mosley had made F1 so successful and it could attract vast automotive and TV money. Bernie had expanded it geographically, too, doing deals with governments, chancers, whatever it took. At the beginning of the decade, 65 per cent of the races were in its traditional home of Europe. By the end, just 47 per cent.

“Spectators and TV companies became casualties of Mosley’s political power play”

This was the perfect time and environment for the one-time south London second-hand car dealer. Instead of sitting around a smoky 1950s room with other dealers trading motors, now Bernie could sell F1’s commercial rights to one of those Clinton and Thatcher-liberated banks which, like Ecclestone in the 1950s, gambled, too. The new F1 owner would often over- stretch itself and fall into the hands of a receiver. Not so different from the 1950s wide- eyed punter, looking to buy a nice little Hillman and going home with a big shiny Humber instead. So, Bernie would buy F1 back at a knockdown price and sell it to a TV company, or a private equity fund – or some to this fund, the rest of it to another party fancying its chances.

A German banker whose employer partially owned F1 got jailed for receiving a bribe in 2006 to sell to Bernie’s preferred buyer, CVC Capital. But Bernie was later found neither guilty nor innocent of offering said bribe after paying $100m to the Bavarian state. “Bargain of the century,” as Bernie later said. That’s how much money was sloshing around in F1 at this time. The real world doesn’t work as many imagine it. It works like this, and F1 is just a super-sharp, speeded-up microcosm of it.

For Mosley, it was always more about control than riches. The complication was that manufacturer money automatically brought power – and there was a lot the manufacturers didn’t like about how F1 was being run. Mosley had cleverly expanded the FIA’s role into the automotive sector, using its F1-honed crash testing expertise to make the NCAP road car safety assessment programme, using his political connections to have it incorporated as the official European Union authentication. Max and the manufacturers each had some instruments of control over the other.

F1 was threatening to bleed itself dry in its performance orgy. The teams were using up vast sums of money on parallel test teams and hundreds of engines, just to test tyres. The manufacturers continued to spend as much as it took to go one-tenth faster than the others. Mosley tried to rein in the spend and contain the fire. If he didn’t, the danger was that the arms race would leave just a couple of teams standing before the whole thing collapsed under its weight. His proposed solution was drastic. With the three performance parameters being aero, engine and tyres, Mosley sought to neutralise the last two elements by bringing in an engine freeze, to be followed by a standard-issue control tyre. F1 was dumbed down two notches. The engines became plug-in components, with virtually no performance difference between them, and an artificial rev limit designed to make them last. Michelin was hounded out of F1 for the sake of easier money, ending inconvenient and expensive competitive striving within F1. Bridgestone would then provide old-tech tyres for everyone from 2007.

Max Mosley’s ultimate power play, using the 2005 US GP to curtail manufacturer power in F1

The manufacturers detested the idea of an engine freeze and formed a group, the Grand Prix World Championship (GPWC), threatening to break away and take some customer teams with them. Mosley stood his ground – and circumstance gifted him the most incredible opportunity at Indianapolis in 2005.

This was the season in which the Schumacher/Ferrari pairing, that had already won five consecutive titles, was stopped in its tracks by a tweak to the regulations banning tyre changes during the race. Ferrari, the only top team on Bridgestones, had been badly compromised against Renault and McLaren, which used Michelins far more able to combine endurance with pace. But the banking at Indianapolis for the United States Grand Prix revealed a damaging flaw in the Michelin. The combination of vertical loads and bumps for six seconds at a time weakened the tyre’s structure until it failed.

Ralf Schumacher was hospitalised after a tyre blow-out put his Toyota heavily into the wall. Michelin stated it could not guarantee the safety of the tyres beyond 10 laps. None of the Michelin cars could race, leaving just the six Bridgestone-shod cars of Ferrari, Jordan and Minardi. Quite incredibly, they were the only three teams not aligned with the GPWC. Talk about luck of the devil! The implicit threat of the GPWC in its opposition to the engine freeze proposal was that its parallel series would leave the FIA’s F1 with just three teams. Surely F1 couldn’t run with just three teams? At Indianapolis, fate had provided an open goal for Mosley to show that he was prepared to run official FIA F1 grands prix with just three teams. While sitting in his back garden at home in England, being kept abreast of developments by phone, Mosley refused to accept the offered solution of a chicane and ordered that the race go ahead as planned. That meant the paying spectators and TV companies became the casualties of his political power play. Fans angrily headed for the exit as the Michelin cars all peeled off to retire at the end of the formation lap, leaving Schumacher to win his only race of the season.

Fernando Alonso powers through 130R at Suzuka in ’06. He would end the year as champion again

Bridgestone became sole supplier in ’07

Minardi’s final season was in ’05

Not only a powerful blow to the GPWC, it also gave Mosley a stick with which to beat Michelin and get it out of F1 after its contract ended. Michelin left at the end of 2006, having helped Fernando Alonso and Renault to their second consecutive championship. Renault’s rearward-weighted car was based around the fantastic traction of the French tyres. Subsequently, the GPWC accepted the engine freeze, its members nervous that the FIA was the arbiter of its road cars’ safety stars rating. Bridgestone supplied tyres to everyone and weight distribution was standardised. In the meantime, entropy had its way at Maranello, where a separate internal political game led to Schumacher retiring after just losing out to Alonso for what would have been an eighth title. With Ross Brawn already heading for a sabbatical, the Ferrari dream team began its dissolution. Todt would also be gone soon enough. Luca di Montezemolo, Ferrari’s ultimate boss, finally got his way. The others had kept him out of the driving seat long enough. Now he set about fashioning a Ferrari for the next era, the signing of Kimi Räikkönen from McLaren the first act.

With the manufacturers under control, for now, Mosley switched attention to his other nemesis: Ron Dennis. The McLaren boss’s card had been marked ever since he’d played an instrumental role in scuppering the proposed floating of F1 on the stock exchange in the late 1990s by revealing its controversial inner financial workings. But it was more than just that. The principled working-class boy made good, Dennis had turned McLaren into a game-changing, blockbusting team and regularly challenged Mosley and Ecclestone. That, and his strong support of the GPWC, didn’t sit well with the aristocratic, autocratic and highly intellectual Mosley. They just rubbed each other up the wrong way.

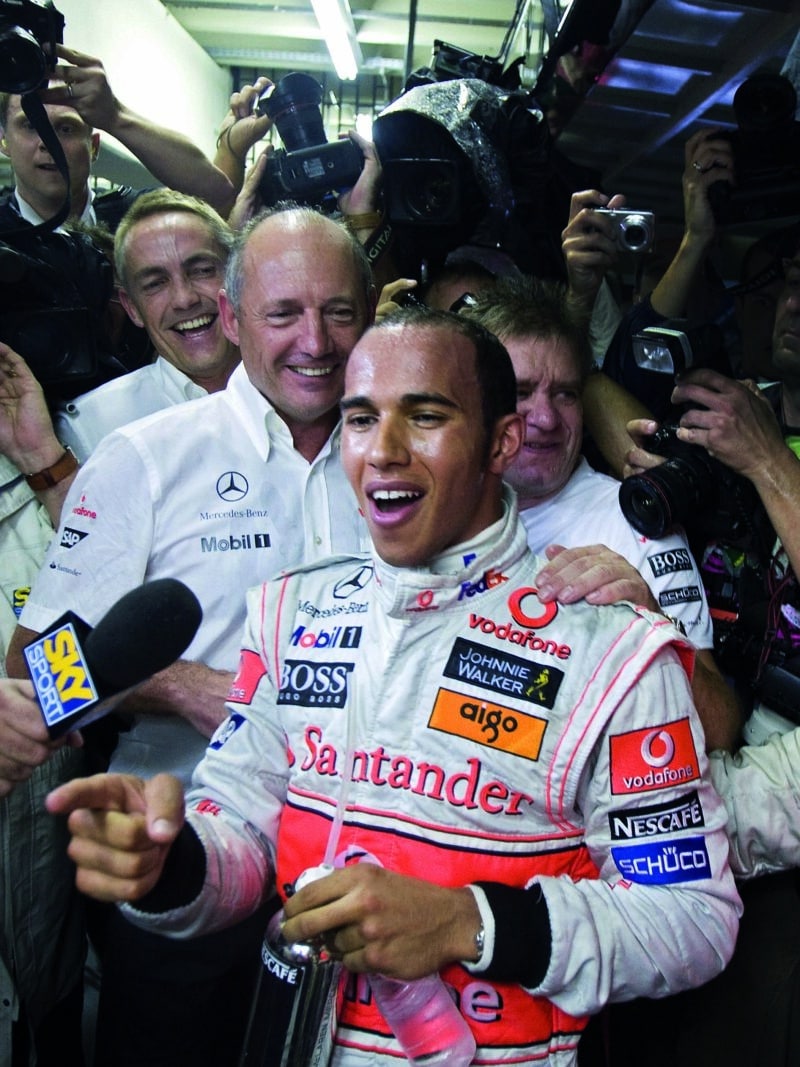

Hamilton celebrates his first title with McLaren, right before the team fell from grace

Antonio Scorza/AFP via Getty Images

Just like Indy in 2005, Mosley was gifted the most wonderful opportunity in the pursuit of his agenda thanks to outside events in 2007. Hindsight suggests he should have been careful what he wished for, but the pieces began to slot in place with McLaren’s signing of Alonso. With the guaranteed performance of a double World Champion on the books, Dennis felt able to risk the signing of a rookie for the other seat. But it was no ordinary rookie. Lewis Hamilton had blitzed his way through karting and the junior categories with McLaren’s financial support from the age of 13. Hamilton was seen, perhaps unfairly, as Dennis’s pet project. Regardless of his backing or the interest that he generated as a black man breaking through, he was a phenomenon, with talent off the scale. No sooner had Alonso established himself at the head of the pride and Schumacher retired, then a new challenger appeared out of nowhere – and in the same McLaren team. The pressure generated by the two in the same place brought an eruption Dennis could not control.

Concurrently, the new era at Ferrari was rocked. Without the support of his old boss Brawn, chief mechanic Nigel Stepney had become seriously disaffected. He supplied a McLaren designer with intimate details of Ferrari’s car in a 780-page document. When Ferrari found out and made the ‘Spygate’ crime known, Mosley chose to get involved. With the FIA as judge, jury and executioner, the team was fined an astronomical $100m and stripped of its championship constructors’ points, denying it a world title. Alonso’s actions during the Hungarian GP weekend had been instrumental in giving Mosley ammunition. Triggered by some tit-for-tat competitive scheming between him and Hamilton in qualifying, Alonso was deeply angered at Dennis, believing he was not living up to pre-season promises that he would have team priority in the chase for the title. Instead, he was having to fight Hamilton as well as the Ferrari drivers. With information on his laptop about McLaren’s possession of the Ferrari data, Alonso threatened to make it available to the FIA if Dennis did not assign him in-team priority. Alonso didn’t follow through and later apologised – but Dennis had already informed Mosley before Alonso did.

The events of that Hungary weekend triggered the long-term decline of McLaren, ultimately cost it its Mercedes partnership, and ensured Alonso’s career fell well short of its potential. It also quite possibly played its part in Hamilton only just failing to become the first and only rookie World Champion. What did happen in that Brazil finale? Had Hamilton’s bizarre technical problems and race strategy gifted Ferrari’s Räikkönen the 2007 title? “I didn’t know at the time,” said Hamilton to my question in 2012. “But I do now. It’s not something I can talk about.”

Brawn’s Button wins Australia ’09

Although Hamilton would go on to win the 2008 title with McLaren-Mercedes, the banking crisis triggered a change of the F1 landscape through an unlikely sequence of events. Honda’s pull-out in the wake of the economic meltdown led to a Ross Brawn-led management buyout of its team, just when Honda had a world-beater in the wind tunnel. But Ross needed an engine – and managed to convince McLaren to allow Mercedes to supply it one. Brawn GP and Jenson Button then pulled off an unlikely World Championship together, impressing Mercedes just as it was angered at being drawn into the Spygate affair. Mercedes had to pay an unbudgeted part of the $100m fine in line with its 40 per cent share in the team and now wished to control its F1 destiny. At the end of the year, Brawn GP morphed into Mercedes. Just like that, McLaren was no longer a giant.

To win the title, Button had to fend off Sebastian Vettel in the Adrian Newey-designed Red Bull RB5, which would come to form the F1 design template for most of the following decade. Newey had joined the freewheeling soft drinks-funded team three years earlier, tired of Dennis’s stiflingly tight reins at McLaren. It could be claimed that the two of the dominant teams in the next decade were given life by Ron’s intransigence.

Although Mosley may have taken some satisfaction from that, in 2009 he would lose his ongoing fight with the manufacturers. Alliances shifted like the tide in these years Ferrari always the balancing centre of gravity, around which the arguments raged. This time Ferrari was on side with the manufacturers. It was a reprisal of the politically-charged 1981 season – but this time with the automotive brands as outlaws. Max and Bernie played the establishment in a neat inversion of history. The teams, led by an incendiary Mercedes still furious at Mosley’s handling of Spygate, vowed to leave en masse the following year, as Mosley tried to force through an extreme budget cap. They would pull back from this brink only on condition Mosley didn’t stand as a candidate in voting for a new FIA president in October. The manufacturers had managed to prise Mosley and Ecclestone apart – Max was mortally wounded by the events he’d triggered in his revenge upon Dennis.

Would the manufacturers have been able to pull off a mass exit, had they been forced to act on their threat? The day of deregulation reckoning had arrived after a couple of decades in the making. The teams now looked nervously around their boom time-funded citadels and their hundreds of employees…

2000 Under the stewardship of Jean Todt, Ferrari’s Ross Brawn-Rory Byrne- Schumacher axis nets the Scuderia its first champion since 1979.

2001 Despite rolling during practice for the season-opener in Melbourne, Schumacher remains unstoppable.

2002 Schumacher takes 11 wins from 17 GPs. His worst result? Third, in Malaysia. He clinches the title in France on July 21, with six races to spare.

2003 A likely consequence of 2002, the FIA changes scoring system and awards points on a 10-8-6-5-4-3-2-1 basis to the top eight. The title is decided at the final race in Suzuka, between Schumacher (six wins to that point) and Kimi Räikkönen (McLaren, one). Eighth is just enough for the German, now F1’s only six-time champion.

2004 Normal service resumes as Schumacher wins 13 of 18 races to wrap up title number seven.

2005 Mid-race tyre changes banned. Bridgestone loses to Michelin. Schumacher scores his only win in the US GP, where all Michelin teams withdraw due to safety concerns. Fernando Alonso is champion aged 24.

2006 Tyre changes return – and a new engine formula (2.4-litre V8) arrives. Alonso beats Schumacher to the title. The German announces he’ll retire at the year’s end. Michelin quits F1.

2007 Lewis Hamilton arrives at McLaren with Alonso. Friction develops. They finish level in the standings, one point behind Räikkönen (gifted a finale win by team-mate Massa).

2008 Needing to finish fifth in Brazil to win the title, Hamilton lies sixth on the final lap. Rain allows him to pass Timo Glock at the final corner of the campaign, taking the main prize from Massa.

2009 Brawn GP dominates the first half of the season, Jenson Button winning six of the opening seven races. Rivals close the gap, but Button completes the job. He then goes to McLaren, while Brawn sells to Mercedes.