“Mark’s engineering background was a huge advantage for us, perhaps the unfair advantage if you like. We were competing in road racing, NASCAR, the International Race of Champions and Formula 1, so there were a lot of things involved. But Mark was the guy who swept the workshop floor at night, drove the truck if he had to and worked on the cars and I think that common thread of having a flat organisation and a personal commitment is really the foundation to our company today and the 66,000 people we employ.

“We were many nights working all night long when we had to get the cars ready and Mark would work late, sleep a few hours and then be up early to drive the truck. He was all-in, passionate about motor racing and he wanted to be a winner and set a standard, perhaps a different standard to what we’d seen in the past.”

One of Donohue’s standout achievements was setting a new closed-course speed record when he achieved 221mph at Talladega Speedway aboard the Penske-developed 1500bhp Porsche 917-30 Can-Am car (see page 97). That record came just days before his ultimately fatal crash at the Österreichring.

“I wasn’t actually there [in Austria] that day,” says Penske, “but it had a big impact on me personally. As I said, Mark was like a brother and he was the heart and soul of the team for so long. It was a big decision afterwards like ‘what do we do?’, but we knew Mark would have said ‘keep going’ so that’s what we did with the support of his family, but it was a tragic loss. Mark was really the catalyst and cornerstone of our success for so long.”

On performance advantages…

Donohue dominated Can-Am with the Penske-Porsche 917-30 – another season where the team exploited a technical advantage

Getty Images / Bernard Cahier

Aside from Donohue’s technical nous, Penske always chased what he terms as “the unfair advantage”, small often innovative engineering solutions designed to find those extra tenths of a second.

One of his early innovations was acid-dipping the chassis of his Trans-Am cars, which would remove the additional layers of paint, adhesives and sound-deadening from a stock chassis in order to make it lighter than the competition.

“We had a body in white, which was your standard unibody-type construction and we found an acid tank in California where we could dip the chassis in and it would take off about 50-60-70lbs by the time it came out. The first few times we tried it the chassis came out more like a sock, but eventually we got the right ingredients in there and we regularly shaved off 50-60lbs.

“Then of course the car roof would have a lot of oil can in it [a term when thin metal visibly flexes, like squeezing an oil can], so we’d put a leather cover over it – which wasn’t unusual then – so you couldn’t see the oil can and we told everybody the cover was to make the car faster, like a golf ball. We had some fun with that one.

“Probably the most interesting unfair advantage was when we built a 30-foot fuelling rig and put the 30-gallon drum on top and we could fuel in about three seconds, and everybody else was taking 8-10sec. That lasted for about two races before we got told to tear it down and take it home.”

On inspiring McLaren…

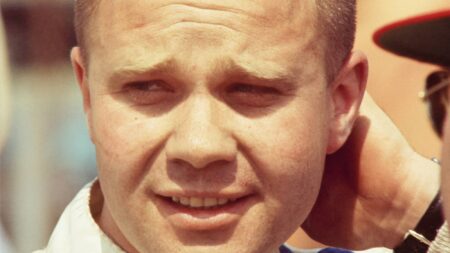

Penske in the McLaren Zerex Special ’round RIverside ’63

Getty Images

A footnote of Penske’s career is the fact that he, almost unknowingly, inspired Bruce McLaren to begin his eponymous business by having a hand in the first car McLaren ever built – through his Zerex Special.