1993 Spanish Grand Prix: Wheel of fortune

Prost survives vibro-massage to take 47th GP win — but only just... The real stories of the Spanish Grand Prix, beyond lap 41, only became apparent when the event was…

Ask the man in the street to name a movie star racer and they will invariably name the King of Cool, Steve McQueen. This is understandable: from Bullitt to Le Mans via that jump over the barbed wire fence into Switzerland during The Great Escape, McQueen has become synonymous with cars, bikes and racing.

But the reality is that while McQueen made the headlines, it was his blue-eyed peer Paul Newman for whom racing became a way of life. Newman not only competed at a high level but also formed his own racing team and it remained his passion until his death in 2008. He came late to the sport – getting serious in the latter half of his life – and it was a film that first sparked his passion. That film was Winning, the 1969 racing movie that today is largely forgotten but would have a profound and lasting effect on Newman’s life.

I got hot on the trail of Paul Newman’s racing life and record after writing my first Hollywood car guy book, McQueen’s Machines: the Cars and Bikes of a Hollywood Icon. At that point it made sense to me to continue with the holy trinity of Hollywood’s old-school car guys, including Newman and James Garner.

It was a thrill to interview Newman by phone; our promised 10-minute chat became a half-hour geek-out session about cars and racing. With my collaborator Preston Lerner, we spoke to many of Newman’s team-mates and owners. And because we knew Newman was ill at the time, it meant a lot to capture so much of his story, and some of his own words, prior to his death.

Newman told a men’s adventure magazine, in 1976, “It’s only partially true that Winning got me interested in racing. I was interested before that, but I hadn’t done anything about it.”

That seems to be true: Newman was born on January 26, 1925, in rural Shaker Heights, Ohio, and his first car was a decidedly plebian Ford Model A, which he later upgraded to a 1937 Packard. Once out of Ohio, and making his way as an actor, his automotive enthusiasm pot began to boil a bit. He bought his first of many Volkswagens in 1953, and complained to his mechanic that it was “just too slow and the brakes weren’t any good.” By this time he’d moved to nearby Connecticut, and was commuting back and forth to New York’s theatre. He later remembered that his mechanic said “Why don’t we just dump a Porsche engine in it? And you’ll still have the back seat, and all the power you need.” So they did, effecting a stock Porsche 1600 engine swap, also adding anti-roll bars, Koni shock absorbers and Porsche brakes up front…

“Later we bored out the Super 90 engine to 1800cc and put a hot camshaft in it. It was a neat little bomb. I guess that was my first hopped-up street machine.” The red VW was the first of many such sleepers Newman would build and own throughout his life, including several Volvo estates packed with Ford and GM V8 engines.

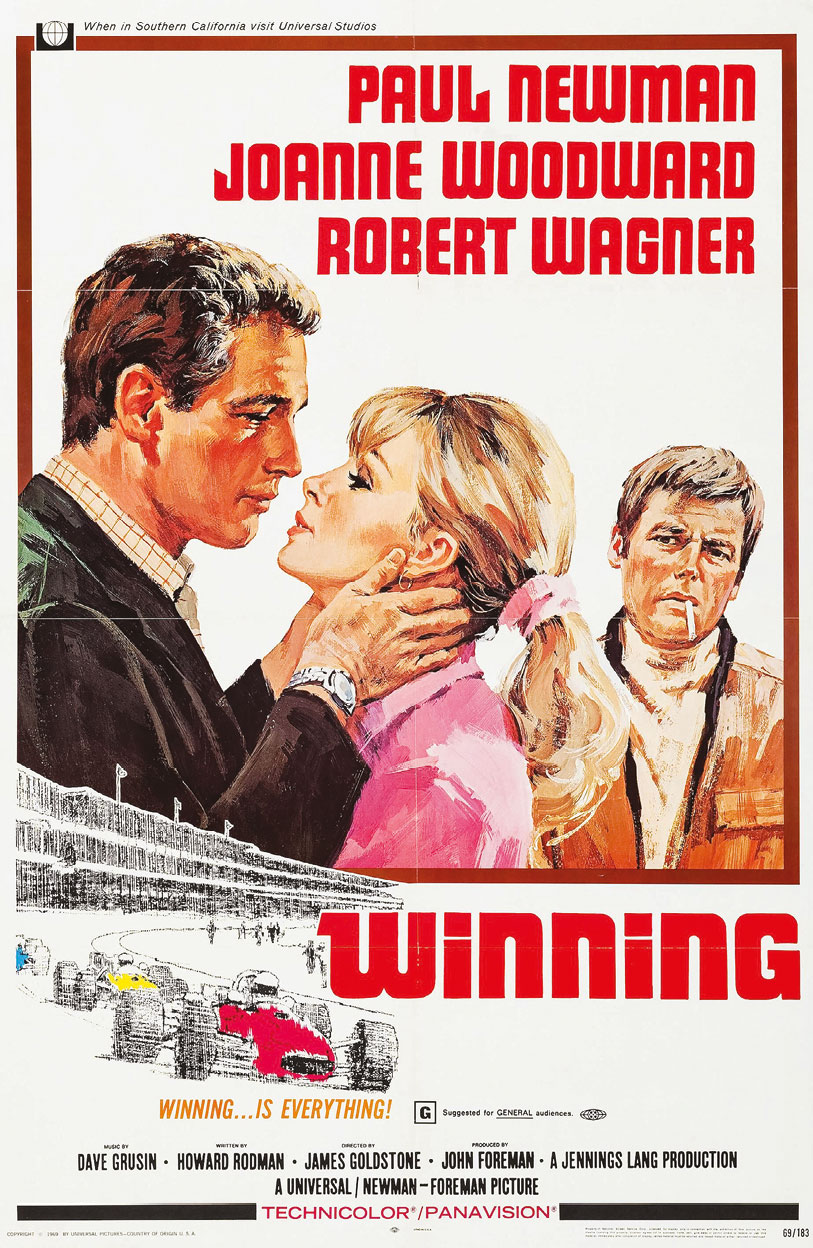

Throughout the rest of the 1950s and most of the 1960s, Newman’s films were relatively devoid of enthusiast automotive content. In Cool Hand Luke, his character drove a decidedly well-used Porsche 356 Speedster, but that was about it. Winning, filmed in mid-1968, changed all that, as this action- and drama-filled love story centred on motor sport. It all stemmed from the novel of the same name, written by Manning Lee Stokes. It was produced by John Forman, with James Goldstone brought in to direct.

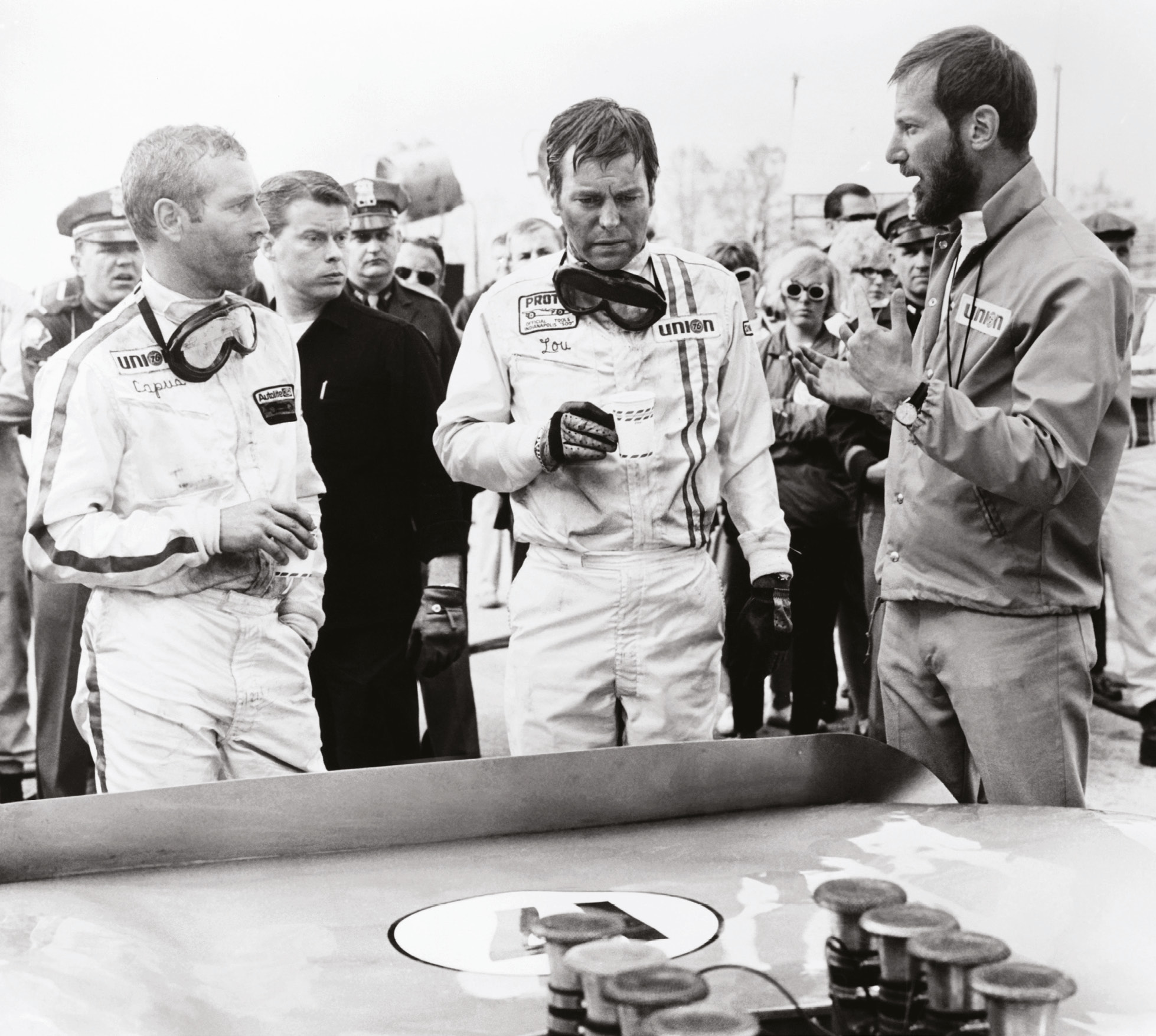

Paul Newman was cast as the primary lead, with his real-life wife Joanne Woodward as his love interest and wife in the film. Robert Wagner co-starred as Newman’s team-mate and foil, who had an affair with Woodward’s character along the trail. The team-mates competed with each other often, sometimes with Frank Capua (Newman) and at others with Lou Erding (Wagner) coming out ahead. All of the sports car racing and NASCAR competition leads up to their battle in the Indianapolis 500.

The original plan for Winning was to produce it as a made-for-TV movie, but once the word got out that Newman was on board, Universal Pictures picked up the film for wide theatrical release. Critical to the movie’s cred as a legitimate racing film was that an impressive roster of real racing drivers, cars, mechanics and footage were employed throughout. Among them were Bobby Unser, Indianapolis Motor Speedway owner Tony Hulman, Bobby Grim, Dan Gurney, Roger McCluskey and Bruce Walkup.

Robert Wagner recalled that “we had to look, walk, talk and drive like real racing drivers.” Racer and team owner Bob Sharp, driver Lake Underwood, Indy winner Rodger Ward and racer-turned-tutor Bob Bondurant had a hand in training Newman and Wagner.

“Critical to the movie’s cred was an impressive roster of drivers”

Newman told Saga: “I just didn’t jump in then and there, you know. I thought and thought about it. I had commitments that argued against it. And the possibilities of an accident and even dying were there from the start. Yet I really felt drawn to the sport…”

“Paul and Robert Wagner were my fourth and fifth students when I opened my racing school in 1968 at Orange County [California] Raceway,” said Bob Bondurant, who had previously taught high-performance driving to many actors and other Hollywood types (including actor James Garner for his role as an American F1 driver in Frankenheimer’s Grand Prix). I asked him: ‘Paul, why do you want to go through the school?’ He said: ‘I have two other movies I could be doing that would make a lot more money, but I want to learn how to drive a race car and see if I like it.”

Wagner and Newman were already by then good friends, as Wagner and Joanne Woodward starred together in her first film a decade previously. Even though Wagner and Newman played characters at odds on many levels, the two displayed an obvious chemistry and trust for and with each other.

“It was clear that Paul just loved it,” said Wagner later. “We did our high-speed practice at Indy, since that’s where the final showdown was to take place… and Paul was in the car lapping every second he could. He was demonstrating that he really understood what lapping at 150mph was all about, that he had learned well from our coaches – and that he had some measure of talent. I swear, if the Indy Speedway had lights, he’d have been out there practising at night.”

Equally critical to having credible stars as racers was having credible cars. The only way to do that was to use genuine race cars for the scenes. In order to capture the feeling of real racing and wheel-to-wheel action, the film needed to include actual racing footage, which in this case was to include action from the 1968 Indy 500, won by Bobby Unser in an AAR [All American Racers] Gurney Eagle. So the producers went to the source, AAR fixing up another Eagle to look exactly like Unser’s winning ride. The late, great Dan Gurney recalled to us that, “It was great fun and a lot of buzz having Paul visit our race shop, get fitted to the car and just spend the day talking with us and eating Mexican food.” We asked Gurney if he would have taken on Newman as a member of one of his sports car teams, to which he replied “Absolutely, without question.” High praise indeed.

Gurney also contributed some spare parts, including a windscreen, roll bar and side-view mirrors so the producers could build a wood-framed buck for in-studio close up and background photos, as opposed to having to cut apart a genuine – still current – Eagle racer. Some of those shots show Paul Newman (as Capua) at the wheel, while others show his brother Arthur wearing a matching racing suit, helmet, goggles and balaclava. Arthur was also blue-eyed, and of similar physical build to Paul, therefore a natural double.

Other than the racing action, much of the Winning plot was pure soap opera. Pro driver meets girl and gets married after a whirlwind romance, but is so dedicated to his sport that he ultimately neglects his wife, who ends up having an affair with his racing rival. That makes our protagonist a more aggressive driver and he goes on to win the Indy 500 after the drive of his life. Reconciliation is attempted after the win, but we never quite know if it happened…

The cars, action footage and background scenes make it work for the racing fan, however. Several ‘in the shop’ scenes are filmed in the Indy Motor Speedway garage while hotel room moments were shot in the actual Speedway Motel. The NASCAR and Can-Am cars in those related scenes are now classic vintage racers. During one of the Indy 500 scenes, there’s a huge crash depicting many cars, that footage taken from an actual crash that occurred during the 1966 race.

Fortunately, the filming of Winning took place without any major mishaps or injuries. The final edited theatre version ran to 123 minutes and the film made its public premiere in the United States on May 22, 1969. It grossed more than $14 million, on a production budget of about $12 million. It went on to rank as 1969’s 16th most popular film, yet received no Academy Award nominations.

It was the only major feature film with an automotive plot to involve Paul Newman until he voiced the character of Doc Hudson in Pixar’s animated feature Cars in 2006.

Newman is often – rightly or wrongly – compared as a racing actor with Steve McQueen. For a time, the two were the most in-demand and highest-paid Hollywood actors in the world. They appeared in two films together, although neither of them involved cars or racing. Each made an epic racing movie, Newman in Winning and McQueen starring and driving in his 1970 endurance racing epic, Le Mans. McQueen finished second in the 1970 12 Hours of Sebring; Newman also raced to a second overall at the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1979. Both headed their own racing teams.

The comparison becomes more difficult to gauge as McQueen began racing at a much younger age than Newman. Paul Newman went on to win four Sports Car Club of America National (SCCA) titles, plus several SCCA professional Trans-Am races. Newman raced in the International Motor Sports Association (IMSA) – and still holds the title as the oldest class-winning driver in the 24 Hours of Daytona. Much of McQueen’s success as a racer also came aboard off-road motorcycles, something with which Newman never dabbled. Those in the know have hinted that McQueen likely possessed more unbridled raw talent for racing, but that Newman was more disciplined, and trained and taught himself how to become a pro-level racing driver.

The two never raced against each other.

Winning co-star and long-time friend Robert Wagner likely sums Newman as well as anyone could: “We did all the driving in the picture. In order to do that, we started practising in Datsun sedans. And Bob Bondurant was there to train us.

“You could tell right from the beginning that Paul had the look of eagles in his eyes. I could see the start of his passion for the whole sport and the racing life. It was fabulous to watch – he was in that car all the time. He loved the cars, loved the drivers, loved the mechanical aspect of it – he loved every bit of all of it. The only difference between us was that he absolutely loved it and I was scared s**tless. We were running 140-150 miles per hour down the front straight at Indy. I always thought the cars were going to fly apart, but he couldn’t stick his foot further into it.

“Paul was a wonderful father, great to work with, loyal to the people he cared about, loved his family and he loved racing. He added a great deal to everyone’s lives, and I was among them. We were very close friends, we had children around the same time, and I have the utmost love, respect and caring for this man. He was one of the most special men that I ever knew. He grabbed life by the throat and shook it, and it’s wonderful that racing came into his life.”

Newman said, famously, “I’m not a very graceful person. I was a sloppy skier, a sloppy tennis player, a sloppy football player and a sloppy dancer with anyone other than Joanne. The only place I ever found real grace was at the wheel of a racing car.” He raced until he was 82 and passed away on September 26, 2008, at the age of 83 due to complications from cancer.

Where does Winning fit in the pantheon of Paul Newman’s great work? Even five decades after its debut, the answer isn’t all that high; this isn’t to say that he didn’t deliver a fine and authentic performance, because he did. But the plot is tenuous, and at some point drones on a bit.

That isn’t to say, however, that it didn’t have a life-changing impact on him, because it obviously did; if not the only thing that kicked off his racing career, it was certainly a major catalyst that motivated him to get his racing licence (just two years later) and start competing. Another thing Winning accomplished, just like his friend McQueen’s Bullitt and later Le Mans, was to demonstrate that projection-screen and faked racing scenes were no longer acceptable in a film centred around motor sport. For that alone, Winning is worth the watch.