Bored enthusiasts are fuelling surge in classic car sales

Our last article, in which I talked about the purity of the no-reserve auction (and the fact that you might be better off not having one), a few of you…

March 20, 1965, Silverstone. It was a particularly wet spring landscape, so much so that the British Automobile Racing Club was eventually obliged to abandon its headline race, the Senior Service 200 for Formula 2 cars. Before that decision was taken, however, there had been a couple of accident-strewn support events, one of the victims of which you see here – an ex-UDT Laystall Lotus 19 that hasn’t been used competitively in the intervening 54 years. But that’s soon to change…

Its driver that day was Harry O’Brien, running under the Aintree Racing Team banner. While Jim Clark (Lotus 30) eventually got the better of John Surtees (Lola T70) at the front of the field, helped by the latter having a couple of excursions, O’Brien had worked his way through the field to third when, according to Motor Sport (April 1965), “He was unlucky to spin off on lap 15 and wreck his Lotus, after having driven very well.”

It transpired that the left-front brake disc had shattered, locking the wheel and spitting the car sharp left into the bank between Stowe and Club. O’Brien took the remains back to his Merseyside base, where they later suffered further damage in a workshop fire, and that’s where the story might have ended. But…

“After his F1 accident, Moss was using 953 to assess whether he retained the instincts to be a racing professional”

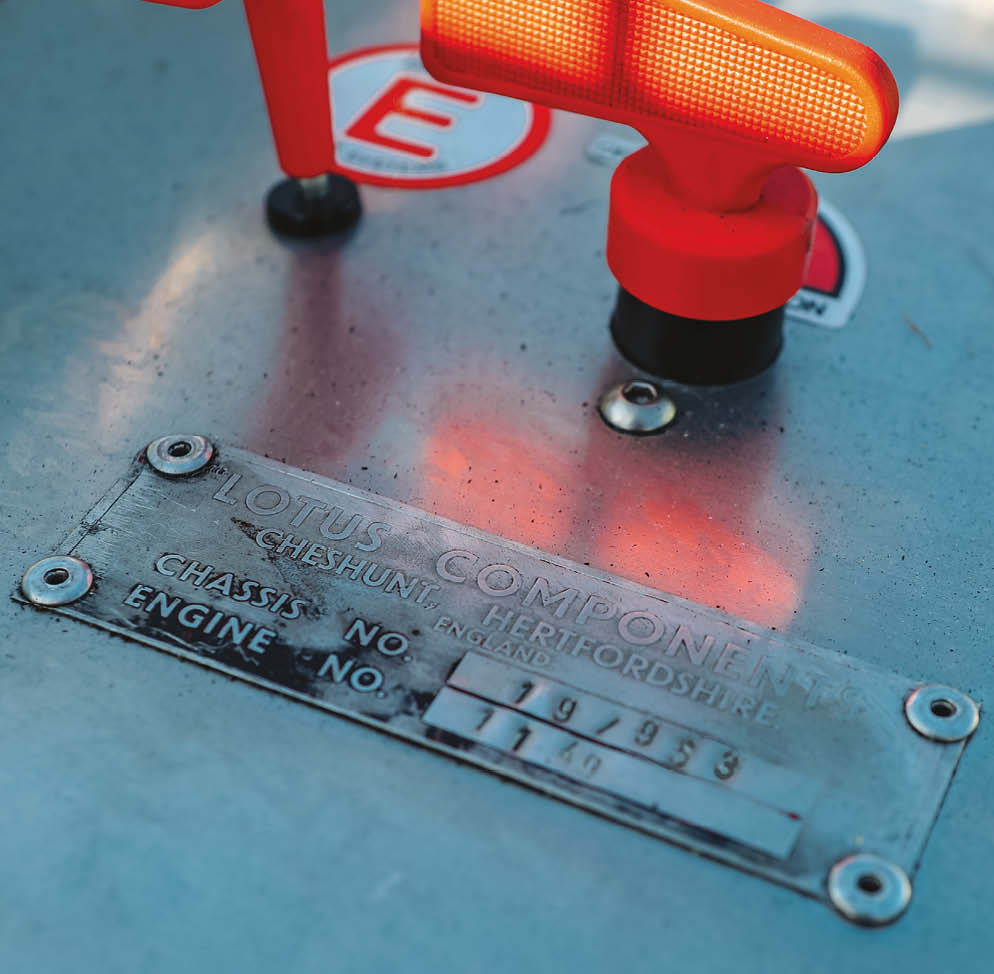

This is Lotus 19 chassis number 953, a car with a more colourful back story than most, and it is now owned by Henley-in-Arden-based Keith Bristow, who plans to use the car this summer in both hillclimb and race events.

It made its debut in 1961, at Goodwood, as part of the two-strong UDT Laystall/British Racing Partnership team owned by Stirling Moss’s father Alfred and one-time business manager Ken Gregory, who also owned chassis 950 and 952. It is thought that Henry Taylor drove the car rather than team-mate Cliff Allison, but despite having accumulated a vast array of paperwork – plus pristine copies of race programmes from every meeting for which the car was entered – Bristow has as yet been unable to verify that to his absolute satisfaction.

Similar uncertainty surrounds several of the car’s earliest races, but what is known is that the inexplicably underrated Olivier Gendebien (four Le Mans victories, winner of the Sebring 12 Hours and Nürburgring 1000Kms, two podium finishes from only 14 F1 World Championship starts) took it to class victories at both Riverside and Laguna Seca towards the end of ’61.

The following season the team retained only 953 and the car was hugely successful in the UK, Innes Ireland winning several races, while Graham Hill triumphed in the Scott Brown Memorial at Snetterton and Masten Gregory took the Player’s 200 victory at Mosport Park, Canada.

There were fewer headlines on the track in 1963, though the car’s CV was embellished when Stirling Moss tested it at Goodwood shortly before Ireland raced it in the Lavant Cup. A year after his serious F1 accident at the same venue, Moss was using 953 to assess whether he retained the instincts he considered essential to a racing professional. He decided not, then stepped away.

South African Tony Maggs was the last top-liner to compete with the car under BRP’s stewardship, taking fourth place in the 1963 Guards Trophy at Brands Hatch, and chassis 953 then passed to privateer Mike Pendleton then, subsequently, George Pitt.

Pitt was due to drive the car in the Oulton Park Trophy on April 11, 1964, but then had a better idea. As Motor Sport reported, “The non-appearance of Jim Clark’s Lotus 30 and Roy Salvadori’s Cooper-Maserati robbed this meeting of much of its interest, for the duel between the 4.7-litre V8 Ford-engined Lotus and the five-litre V8 Maserati-engined Cooper could have been quite something. As it was, both cars were still being worked on at their respective factories. These two cars were intended for the main race of the day, the 37-lap Oulton Park Trophy and, as last year, there was a noticeable absence of large machinery.

“Clark was offered a Lotus 19 by George Pitt, this being the ex-BRP car with 2½-litre Climax engine, and he proceeded to set fastest practice lap ahead of Jack Sears in the fierce Willment AC Cobra, followed by Bruce McLaren in his newly acquired 2.7-litre Cooper Special, which used to be known as the Zerex Special when owned by American driver Roger Penske. This was throwing a lot of oil about and looked as if it wouldn’t last. The only other big cars to start were John Coundley’s 2.7-litre Lotus 19 and Tom Fletcher’s Lister-Jaguar. The field was further depleted after Jackie Stewart had written off the venerable Ecurie Ecosse Cooper Monaco during practice, and it is not surprising that he has now declined to drive this car or the Tojeiro Buick any more.

“Despite these incidents 25 cars came to the line in mild, dry conditions and, as expected, Clark took the lead and held It comfortably. He broke no records, but his exemplary performance with a relatively old car pleased both the crowds and George Pitt and his mechanics, who had spent the previous night checking over a car that was already well prepared by any standards.”

The following month Pitt guided 953 to victory at Aintree, but it was then sold to Bolton car dealership Entwistle & Walker and, subsequently, O’Brien. Which is where we came in.

For the next 30 years the car remained untouched, except by those aforementioned flames.

“It basically just sat there in the workshop,” Bristow says. “And then, in 1996, a chap named Kelvin Jones persuaded Harry to part with it. He bought the chassis, sent it to a man who had built Lotus 19s in period, Ken Nicholls of Nike Cars in Devon, and asked him to repair it.

“It was provisionally entered for the 2006 Madgwick Cup at the Goodwood Revival, but the restoration was still incomplete and the car didn’t materialise.”

Three years later, its second career still on hold, Bromsgrove-based Lotus specialist Paul Matty acquired the car and he commissioned Andrew Tart of ATME to complete the restoration.

“We started it up, to confirm that the cylinder block was damaged and needed replacing”

“I’ve worked on many Lotuses,” Tart says, “but this was the first time I’d done a 19. It was a complete car, but it had just been dropped together to keep all the components in the same place. Ken Nicholls had done a good job repairing the chassis, but there was still some aluminium work to be done – floor, sills, complicated areas around the radiator – and we did all of that. It was taking time, though, and Paul was getting a little bit anxious about the number of hours that were going into it, so decided to finish it off in his own workshops. We’d completed it as a rolling chassis, though we didn’t start the engine because we felt sure it was suspect, but it was now sitting properly on all four wheels, with suspension set-up all done. It just needed a few basic bits and pieces and, importantly, a decent engine. Paul had the details finished and in 2012 did a short demo run at Shelsley Walsh, during a Lotus celebration, and then put it on display in his showroom.”

During that weekend, the attending Moss signed the engine cover – a detail that still survives to this day.

Bristow admired the car whenever he passed his friend Matty’s premises. “I love the way the car looks and its very particular history,” he says. “I just think it’s a magical symbol of motor sport from that era.” Late in 2016, he negotiated a deal to buy the 19, sold a lovely Ralt RT1 F2 car he’d been using on the hills to funds the restoration – and it went back once more to ATME to be primed for a full racing return.

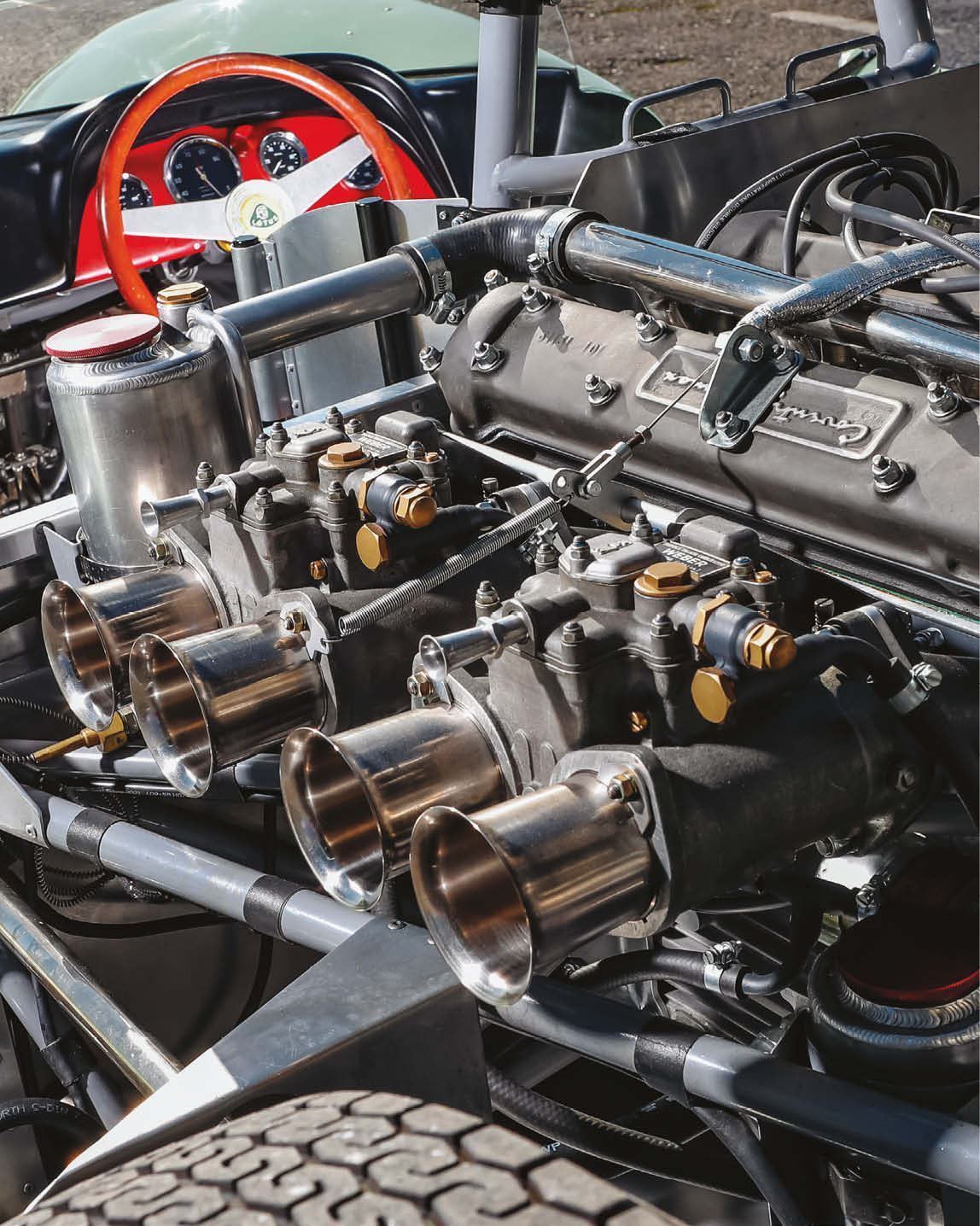

“We started it up,” Tart says, “to confirm the cylinder block was damaged and needed replacing. We’ve got the original 2.5-litre Coventry Climax FPF head on it and, very importantly, the original carburettors, so we then built a new bottom end, which is what we have today. It came back into our workshop again about two years ago, but there were supply delays with some engine parts.

“There are lots of original bits and pieces, including the steering wheel and the gearknob, both beautiful pieces of kit. The gearbox is original, too, a Colotti Type 32 that was used as an alternative to either the ZF or the Lotus ‘queerbox’ [period nickname for a famously unreliable transaxle].

“Although it’s quite a big car, Keith is a big bloke and the standard driving position is crap. You are pushed to the right, too close to the gear linkage, and the steering wheel is at a horrible angle, not square in front of the driver. So we decided to alter the steering column slightly to square the wheel up, move it away from the gearlever and just make it more comfortable, because there’s no point having the car if you can’t drive it properly. We’re using an original-style seat, but we’ve added a shoulder rest for Keith to lean on, which is important, and moved the pedals further down the footwell.

“It took a long time to get some of the bits right – turning complex metal around on itself to avoid any raw edges isn’t easy, but that’s how the car was in period. It just takes time, but it’s worthwhile because it’s a proper bit of kit and you want to do the job as well as you can. We made a new wiring loom, cotton braided as it once was, and went to a lot of trouble to find original switches, fuse boxes and so on – all nice bits of late 1950s/early 1960s automobilia. The gear linkage has a nice interlock mechanism, which was unfortunately missing, but coincidentally I had a Lotus 18/21 grand prix car in the workshop with the same linkage, so was able to copy it.”

“The highlight is probably that Jim Clark raced it once – and won”

At the end of February, sitting on a nice set of Borrani wire rims, the car was taken for a gentle shakedown at the Curborough sprint course, in Staffordshire – almost as far removed as it’s possible to be from some of the venues where it achieved its period successes. “It has taken longer than anticipated to get it ready for competition,” Bristow says, “but we felt it was such a special car that we didn’t want to cut any corners. It was important to get everything right – and I think Andrew and his team have done a fantastic job.”

The car will return to Shelsley early in May, for its first competitive outing since 1965, and Bristow also plans to run it at Loton Park, Prescott and Château Impney, before later in the year taking it circuit racing in the Historic Sports Car Club’s Guards Trophy. “I’ll enjoy developing the car, making it competitive and we’ll see where we get to,” Bristow says, “then next year my ambition is to get a top pro to race it at Goodwood. The car’s history is amazing, though for me the highlight is probably the fact Jim Clark raced it once – and won.

“In August 1963 Autosport mentioned that 953 had been ‘probably the most successful sports car to be seen in the past few seasons’ and we wanted to respect that – not to make a rocket ship, but to restore an important period car to period spec.”