Spooling for a fight

In essence the RS500 was a road car – and originals remained that way. The racers, then, weren’t all they seemed

Here’s a question to furrow the brow of even the most ardent fan of late 1980s tin-top racing. In total, how many racing Sierra RS500 Cosworths did Ford build? The answer does not appear easy to come by: in their era these utterly dominant 500bhp monsters raced everywhere from the UK to Australia and all over Europe in the BTCC, WTCC, ETCC and DTM. There were the factory Eggenberger cars, the factory-supported Rouse cars and all those that were built up by smaller teams with more modest budgets. But how many, exactly, were there? Perhaps a touch surprisingly, the

answer is none…

The histories of the real Ford Sierra RS500 Cosworths and their racing relatives are indivisible, for both groups relied entirely on each other for their existence. The race cars could never have raced without the road cars first gaining homologation, and the only reason the road cars got built was so the race cars could be created. But the fact is that only 500 RS500 Cosworths were built, including four prototypes, and every one was a road car. The racing ‘RS500s’ were nothing of the sort, but everyday, common-or-garden Sierra Cosworths upgraded to RS500 specification the moment the real RS500 was homologated. Despite the fact that, famously, all RS500s were right-hand drive, if you look those that raced in the DTM and European Touring Car Championship, you’re likely to notice a certain prevalence of cars with steering wheels on the other side of the cockpit. Semantics? Perhaps not if you’re the owner of one of the 500…

The RS500 was a homologation special in the truest sense of the phrase. Ford had homologated the original Sierra Cosworth by building the stipulated 5000 units required for Group A racing and rallying; this then entitled them to build a further 500 ‘evolution’ cars. And to look at, an RS500 road car and the RS Cosworth upon which it was based appear very similar indeed. The RS500 has a different front bumper and another element to its rear spoiler, a thin pin-stripe of paint and a badge but inside the cars were identical, even the numbered plaque most carry being an after-market add-on by the owners club. Nor was the engine exactly the animal you might expect of such a car: it was more powerful, but with a mere 224bhp, to the tune of slightly less than 10 per cent.

But changed they were, and to an extent their modest enhanced appearance and performance would never suggest. The 2-litre twin-cam 16-valve engine had a thicker block, with smaller core plugs, and a Garrett T04E turbo the size of a medicine ball in place of the standard T3 unit of the normal car. It had a different inlet manifold and eight injectors, though only four were plumbed in. The throttle body width went up from 52mm to 76mm, a large-capacity intercooler was fitted and a revised cooling system too. At the rear of the car brackets were fitted but nothing mounted to them, so that racing versions could have different suspension pick-up points and rose joints.

Even those small visual changes were critical: the new front bumper had cut-outs to increase airflow and those that were already there were widened. The fog lamps were removed (but supplied in the boot) and mesh grilles fitted while there was a lower front splitter, whose downforce was balanced not only by the twin rear wing but the Gurney flap on the its upper level.

The car, in street form, was a caged lion, claws clipped, padding irritably around its enclosure, waiting for any opportunity to cut loose. And it required remarkably little: a ported head, a pair of hot cams, a lowered compression ratio and a new ECU map and, boom, 500 scarcely controllable horsepower were yours. The crank, rods and even the valves remained standard, despite a rise in boost pressure from 8 or 10psi to something nearer 35psi.

Of course anyone who tried to race such a car without further modification would be inviting failure, just as anyone who tried to drive one on the road would more likely be inviting disaster: the homologation cars provided merely the framework around which a racing car, utterly transformed in every way, could be created. To handle this power even the Borg-Warner gearbox taken from the Mustang would need beefed up internals, as would the diff, along with bespoke race suspension and all usual racing refinements.

Most of the work was done by two different teams: the aforementioned Rouse and the Swiss-based Eggenberger outfits. And within those homologated hard points and depending on your available budget, they’d start with a Ford 909 seam-welded motor sport shell and from the roll-cage upwards build you the racing car of your choice.

Not that they’d reach the same results. Paul Linfoot is registrar of the RS500 Owners Club. He says: “A complete Rouse car might cost between £80-£100,000, strong money in those days. An Eggenberger car? Nearer £200,000.’ Linfoot says they look similar but are in fact completely different and he should know: he owns one of each. “My Eggenberger car has magnesium suspension, Bosch fuel injection rather than Zytek. It has a better wiring loom. While the Rouse car has lots of gauges, the Eggenberger has one rev-counter and digital readout with page after page of data. Really I could spend all day describing the differences but if you just sit in it it feels different, like a Rolls-Royce to a Mondeo.”

Eggenberger cars also tended to have wider tracks than Rouse machines but, oddly enough, less power. While the Rouse cars all had 500bhp minimum, the Eggenberger cars tended to produce 450-470bhp, because they were intended for longer distance races in the ETCC and WTCC and reliability was crucial.”

But regardless of who built your ‘RS500’ race car, when you went out to race it, chances were the only opposition would be other RS500s. In the BTCC with the driving talents of the likes of Andy Rouse, Steve Soper, Tim Harvey and Robb Gravett at the wheel, RS500s won 40 races on the trot between 1988 and 1990, a feat unapproached before or since. The RS500 won the World Touring Car Championship for Ford in 1987 and the European Touring Car Championship in 1988. It also claimed the Bathurst 1000 in both 1988 and 1989. Indeed it was Dick Johnson, who won the race 1989 race, who probably got the most out of the RS500, eventually claiming up to 600bhp from its 2-litre engine complete with a six-speed gearbox and strong differential, good enough says Linfoot for the car to be timed at well over 200mph down Bathurst’s endless straight, a prospect I find more terrifying than I can say.

Inevitably it all had to end. The Sierras had turned touring car racing into RS500 racing and that was never going to be allowed to last. And in time-honoured fashion, the cars weren’t banned, the rules were simply changed to render them ineligible. They were replaced by Super Touring Cars, technologically space-age by comparison to the always rough and ready Cosworths, but with normally aspirated engines, lacking entirely their phenomenal grunt. In Australia, they succumbed to the Nissan Skyline, which not only had the power but the four-wheel-drive system that enabled it to be used effectively.

All that’s left are the memories of those fire-belching cars, the wonderful liveries from the likes of Kaliber, Texaco, Mobil 1 and others, and drivers grappling with torque curves shaped like the Matterhorn. We may not see their like again, but how lucky we were to have seen them at all.

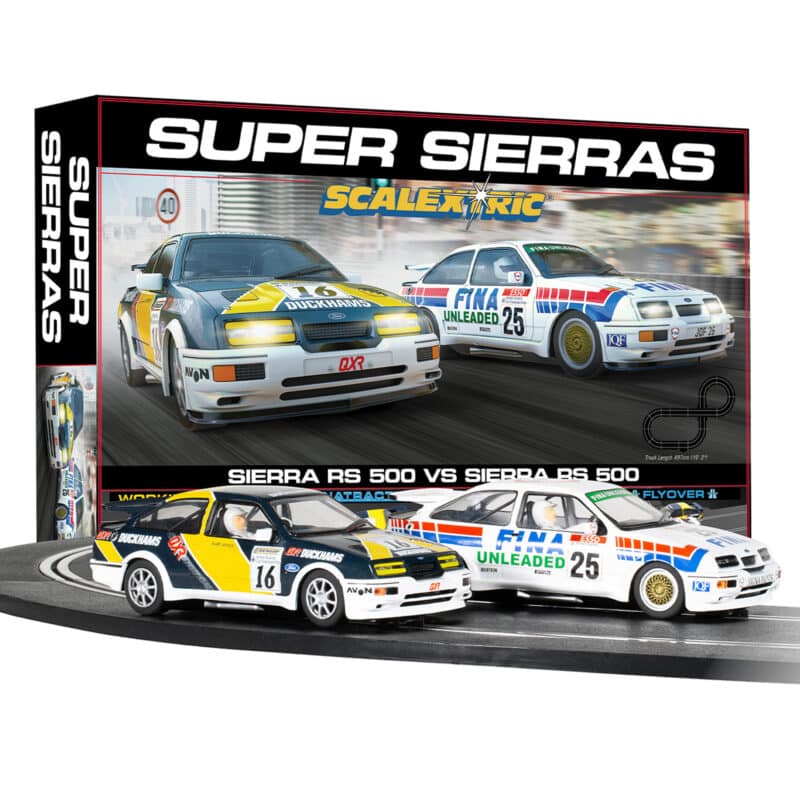

Scalextric Super Sierras Race set

£129.99

Take a nostalgic journey back to the thrilling Group A era of the 1980s with the Scalextric Super Sierra Set. Battle with two Ford Sierra RS500s — complete in old-school livery with working headlights — on a track with multiple layout options and a fly-over bridge.