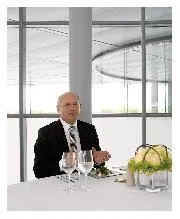

As far as long-term planning was concerned Dennis confesses that, to some degree, Rondel was flying by the seat of its pants. Yet quite early on the team had identified some trends and traditions which were worth keeping an eye on. So did Ron ever imagine that the road down which he had decided to travel would eventually lead him to F1?

“Teams often spread themselves wide in those days,” he ponders. “I recall, for example, that McLaren was planning to build an F2 car for the 1972 season as well as F1 and Can-Am cars. And F1 drivers at the time would fill out their much shorter seasons with F2 drives. For instance, the 1971 European Formula 2 Champion, Ronnie [Peterson], was already proving a spectacular force in F1. And our own main driver [in F2], Tim [Schenken], would have finished third in the F1 British Grand Prix that year if his gearbox hadn’t failed in the works Brabham BT33.

“So naturally, Neil and I at least held thoughts about F1 in the back of our minds, but that’s where they had to stay. Remember, there were 25 Formula 2 races in this, the fifth and final year of the 1600cc regulations, so trying for success in F2 consumed all our energy and resources. Don’t forget either that we didn’t design our own car at this stage — in 1971 and ’72 we ran Brabham BT36s and BT38s, though we did modify them as we saw fit.

“In short if this ‘road we were choosing’, as you put it, would eventually lead to F1 then we certainly wouldn’t resist it, and our competitiveness in 1971 and ’72 was encouraging — Tim finished fourth overall in our first F2 season. But don’t think we were ever seduced into taking our eye off the F2 ball.”

“Graham Hill knew we were serious players, and admired our thoroughness”

So just how important for Rondel was Hill’s win in the Easter Monday 1971 F2 international at Thruxton?

“Important? Very,” says Ron. “It went a long way to validating our team and our competitiveness. Most of all, it confirmed in mine and Neil’s minds that the leap in the dark we’d taken following Jack [Brabham]’s retirement hadn’t been a rash move.

“Of course, Graham was still a world-class F1 driver, so don’t think we weren’t grateful for his contribution. But Tim also did us proud. The fact that Graham, a two-time World Champion, was willing to drive for our untried team on an occasional basis speaks for itself, I think. He knew we were serious players, and he admired the thoroughness with which we prepared for our inaugural season.”

Hill speaks to Peter Gethin at Thruxton in ’71

Yet in so many ways Rondel was ahead of its time, both on and off the track. Early on Ron and Neil produced a promotional brochure outlining their aims and ambitions — in itself something of a novelty at the start of the ’70s — and a timely sequence of events brought them into contact with someone well qualified to help.

The father of Dennis’s former fiancee owned a large antique dealers and told Ron of a Ferrari owner with a taste for antiques who often visited his premises. Ron promptly despatched a brochure to the individual concerned who turned out to be City shipbroker Tony Vlassopulo, a great motor racing fan and a regular commentator at BARC club meetings. Tony took over as company chairman and helped greatly in smoothing out the ups and downs of Rondel’s maiden racing season.

Schenken to this day has hugely positive memories of his three seasons driving for Rondel, his overwhelming recollection being that Dennis and Trundle were in effect engineering a sea change in the way people tackled professional motor racing.

“Some unkind souls nicknamed Rondel ‘Team briefcase’ or ‘Team dream’”

“In those days, in terms of transporters, the best you could reasonably hope for outside F1 would be some greasy and grimy Bedford TK truck which had seen better days and was so filthy you wouldn’t want to go near it for fear of soiling your clothes,” recalls the 67-year-old.

“But Rondel’s truck was immaculate and set the tone for some pretty merciless mickey-taking among those who thought Ron was a bit too smart. Some unkind souls nicknamed Rondel ‘Team briefcase’ or ‘Team dream’, but I think it’s pretty fair to say that he had very much the last laugh as far as those detractors were concerned.”

Tim’s wife Brigitte also contributes to the recollections of those happy days by reminding us how immaculate Rondel’s team base at Feltham, near Heathrow, was turned out, with spotless decor and upstairs offices overlooking the preparation bays. It was another sign of what we could expect from RD in the future, even though it was only for the 1973 season.

After winning the final race of the 1.6-litre F2 category in Cordoba, Argentina at the end of 1971, Tim looked forward to continuing with Rondel as an adjunct to what promised to be a busy ’72 as a member of the Ferrari endurance racing team as well as remaining with Brabham in F1 now that Ecclestone had bought it.