Stirling’s time, 1min 39.1sec, was half a second faster than anyone else, and he reckoned his next lap would have been quicker yet, had it not been interrupted by a serious accident to Innes Ireland in the tunnel.

“Lotus had their new 21s at that time, and Rob had tried to buy one for me, but Esso – who sponsored Team Lotus – wouldn’t let [Colin] Chapman sell him one. It had a ‘wrong way round’ gearbox, and when Innes went to change up to fourth he got second, locked up the back wheels and hit the barrier backwards.”

No seat belts in those days, of course, and on impact Ireland was thrown – a considerable distance – from the car, being very nearly run over by Lucien Bianchi’s Emeryson as he lay in the road. Stumbling to his feet, he made it to the relative safety of the pavement and lay down, bleeding profusely from a badly gashed leg. Moss stopped at the scene.

“Innes was pretty knocked about. I got him a cigarette from one of the marshals while we were waiting for the medical people to arrive, and the only other thing he asked me was, ‘Is my wedding tackle all right?’ Dear old Innes… Later on that year he won at Watkins Glen – the first GP victory for Team Lotus – and then got dropped. Chapman was pretty horrible to him.”

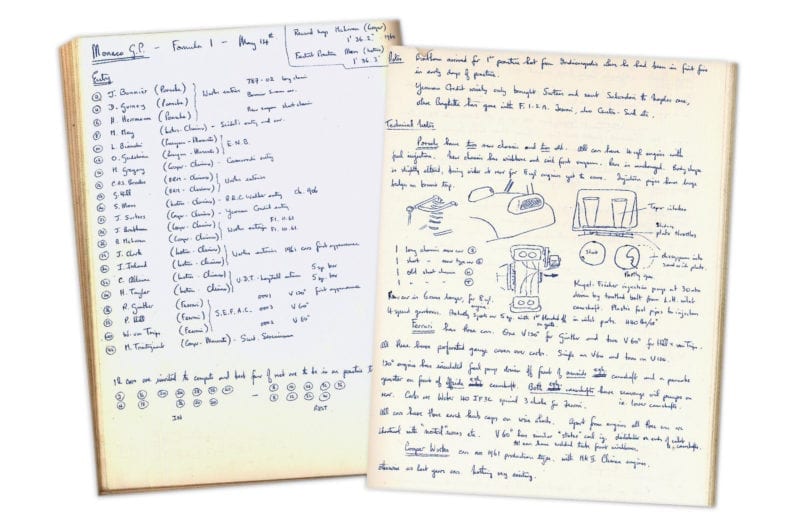

On Sunday afternoon they lined up like this: Moss, Clark and Ginther on the front row, with the Hills – Graham (BRM) and Phil (Ferrari) – on the second, then von Trips (Ferrari), McLaren (Cooper) and Brooks (BRM) on row three, followed by the Porsches of Bonnier and Gurney. As was the tradition in those days, only 16 cars went to the grid, the last of them being the Cooper of World Champion Jack Brabham.

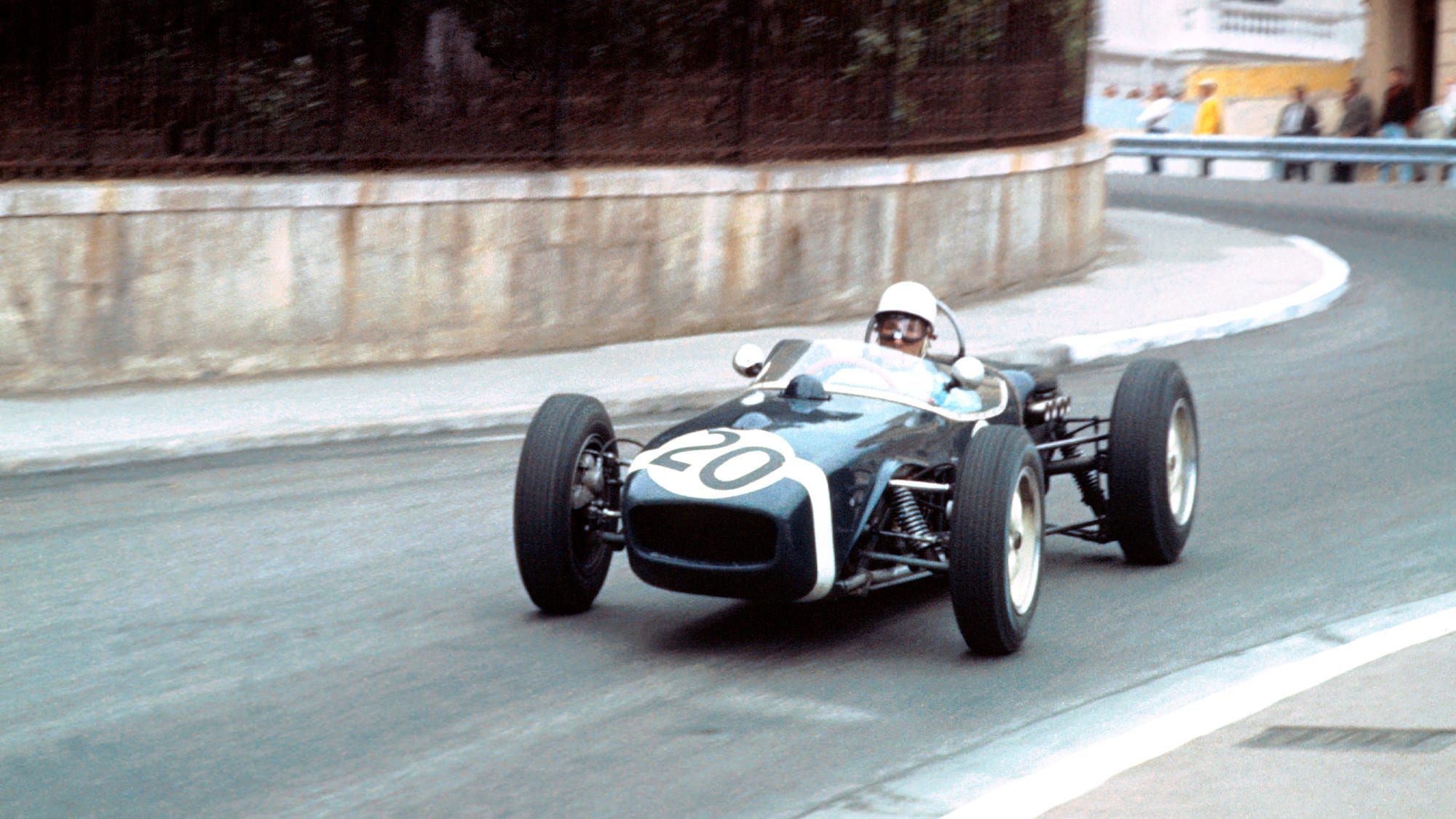

Pole man Moss (left) couldn’t prevent Ginther’s Ferrari from slipping ahead at the start, and then Clark (right)

Klemantaski Collection/Getty Images

It was hardly surprising that Brabham was back there, for he had arrived from Indianapolis on Thursday morning, taken part in the first practice session, then dashed back to America again to qualify for his first 500. By Sunday lunchtime Jack was back in the Principality once more, and admitting to feeling a touch jaded.

On the grid Moss, too, had his concerns, for he’d noticed what looked like a cracked tube in his car’s spaceframe chassis. “I called Alf over and said, ‘Is that a crack?’ He said yes, it was, and off he went to get an oxyacetylene torch. The crack was right next to the fuel tank – which was full, of course. He covered the tank with wet cloths and started welding…”

Francis was indeed made of stern stuff. “It was a very brave thing to do,” Walker observed. “I watched him for a bit, but after a while discretion overcame valour, and I retired to a safe distance…”

“Everyone was leaning over,” said Stirling, “watching what he was doing – and then when he lay down on the road and lit this thing, everyone ran for it – including me! Rather doubt anyone’d be allowed to do anything like that now…

“Alf was an amazing bloke. He could be bloody irascible – every now and again he’d get pissed off about something and throw his tools in the air, and at times like that you just kept your distance until he’d simmered down again. But if he was in a good mood, he was quite amusing. He knew nothing about designing a car – as he proved when he tried it! – but as a mechanic, particularly as an improviser, he was a genius. I trusted him absolutely – when he finished welding the tube that day, I never gave it another thought.”

Ferrari’s Richie Ginther leads, with Jim Clark and Moss in pursuit at the start of the ’61 Monaco GP

The day was hot, and for the first time Moss had a drinks bottle in his car: “Actually it was a Thermos flask, mounted in a bracket to the left of the seat. Races were long in those days…”

In the same vein there was one more thing to be done: Stirling decided that in the interests of ventilation he would like his car’s side panels removed. “It was only a bit of glassfibre, but we had to get permission from the Clerk of the Course. He said it would be OK so long as there were still legible numbers on the car, so we put a new one on the back.”

The rules decreed that every car had to be in position on the grid five minutes before the start, but although the Walker Lotus didn’t make it, there was a greater… flexibility in those days, and anyway Stirling was Stirling.