The unfulfilled promise of Rockingham Speedway

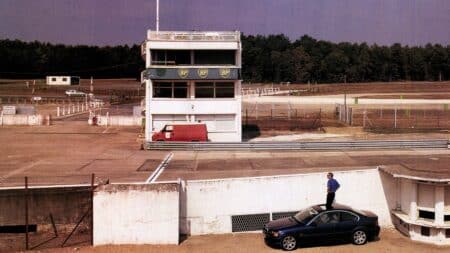

Rockingham Speedway First car race 2001 Last car race 2018 Lap record 24.908sec, Jimmy Vasser, Lola B02/00, 2002 Rockingham, the first banked oval circuit to be built in Britain since…

Track visit

Introduced as a rival to Bathurst, just down the road, Gnoo Blas was a scarily fast road circuit in New South Wales. Jim Scaysbrook rediscovers the racetrack they pronounced ‘Noo Blah.

Rivalry is one of the prime tenets of motorsport. But in the case of the long defunct Gnoo Bias circuit in Orange, 177 miles west of Sydney, motor racing was simply the common factor in an intense contest with the neighbouring city of Bathurst, just 35 miles back down the road. Bathurst and Orange had populations of similar sizes, around 18,000 each in the early 1950s, but Bathurst had one thing that Orange did not — Mount Panorama.

‘The Mount’ had become Australia’s premier circuit from the moment it opened in 1938. But the war took its toll on the venue, and little in the way of maintenance or improvements had been done by ’52. The promoters of the annual Easter car races, the Australian Sporting Car Club, had been at loggerheads with Bathurst Council for years, threatening to abandon their traditional meeting unless changes were made. The pits and paddock area, in particular, was a disgrace, the slightest shower of rain turning the entire area into a sea of mud. The road surface too had seen better days, with crumbling edges and numerous potholes that were routinely filled with asphalt until the sealed area resembled a patchwork quilt. Bathurst Council drove a further nail into relations by doubling the surcharge on each spectator ticket.

After the Easter 1952 meeting the ASCC was fed up, and this time it had a new arrow in its quiver. After a series of not-so-secret meetings with Orange City Council, the ASCC announced it would not be back at Bathurst for Easter ’53, leaving the weekend as a bikes-only fixture. In a short space of time, a 3.75-mile stretch of public gravel roads was mapped out and tar-sealed using mainly voluntary labour. The track was christened Gnoo Blas, meaning ‘twin shoulders’ in the local Aboriginal dialect — a description of the two mountains, Canobalas and the Pinnacle, that overlooked the area. A date of October ’52 was announced for the opening meeting. This came and went after savage winter weather delayed the completion of facilities, but all was in readiness for ’53.

Roughly triangular, the circuit had some gentle rises and falls but was basically flat, with Bloomfield Mental Hospital located on the inside of the southern section and the Tiger Aerodrome in the northern infield. As a layout, about the only thing really going for Gnoo Blas was that it was extremely fast, with right-angled corners at three points. The most challenging section came halfway around the lap where the road flicked right, then left over Brandy Creek, at a section known as The Sweep.

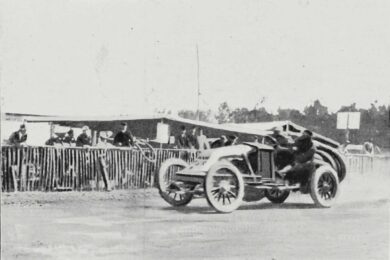

It was here, on the circuit’s opening day, that Alan Boyle, a rapidly rising star of the motorcycle scene, lost control of his bike and was killed instantly. That first meeting took place over the three-day holiday weekend of January 24-26 1953, then celebrated as Anniversary Day and now as Australia Day. The bikes had the circuit for Saturday, then cars practised on Sunday and raced on Monday. It was meant to be a shakedown for the critical Easter date just two months away, when the question would be answered as to whether the Bathurst tradition could successfully be broken.

The media coverage generated by Saturday’s crash resulted in a bumper crowd of 15,000 on Monday for a programme of eight handicap races. Before he threw a tread from a rear tyre, Jack Murray and his Day Special established the initial outright lap record at 2min 32sec, a shade under a 90mph average. The car was derived from a Type 39 Bugatti dating from 1926 that had been driven to victory in the ’31 Australian Grand Prix at Phillip Island by Carl Junker. Now with a 5-litre Mercury engine, Murray charged from the back of the grid, but flung the Day Special into a ditch after failing to take Mrs Mutton’s Corner. Almost simultaneously, a three-car accident left former fighter pilot Curley Brydon with a broken arm and wrist — and a written-off MG TC. Only a handful of cars completed the race, won by David McKay’s TC.

Now it was time for the real test. At the time, strict import restriction in Australia meant that tyres were in short supply, and racing tyres almost non-existent. Consequently, Gnoo Blas’s 1.3-mile main straight (originally Mental Straight but changed to the less offensive Hospital Straight) was a real punisher, tyre failures being commonplace on the more powerful cars. By Easter the situation was critical, but fortunately the cool autumn weather had arrived in the region, which is 700 metres above sea level, and rubber catastrophes were kept to a minimum.

The question of spectator loyalty was answered in the negative, however: only 7,000 turned up, with 10,000 claimed for the rival motorcycle meeting on the same day at Bathurst. Star of the day was Tom Sulman and his blown 4C Maserati, which took five wins from as many starts. Peter Vennermark, in the ex-Raymond Sommer 4CL Maserati, pushed the outright lap record to 92 mph, although the car’s brakes collapsed under the strain.

A third meeting for 1953 took place in October, the feature 100-mile New South Wales Grand Prix being won on handicap by Jack Robinson’s Jaguar XK120, with Jack Brabham’s Cooper-Bristol collecting a separate award for the fastest race time. But within the ASCC ranks there was much trouble brewing, and a splinter group, calling itself the Australian Racing Drivers’ Club, broke away and headed back over to Bathurst, where it resumed promotion in ’54.

Now the rivalry was really on. Easter Monday 1954 saw the new ARDC staging the NSW GP at Bathurst, while the ASCC had its own show at Orange. Most of the top names, including Stan Jones and Brabham, went to Bathurst, but Gnoo Blas drew a healthy crowd to see New Zealander Fred Zambucka push his 2.9-litre supercharged Maserati to a new lap record of 2min 15sec — the magic 100mph lap.

The announcement of this ‘record’ was treated with much raising of eyebrows, and was generally reckoned to be a publicity stunt to claim the title of Australia’s fastest circuit. It would be a while before anyone remotely approached the figures quoted on that day. Down the Mental Straight the Maserati reached 142mph, fast enough to keep Arthur Wylie’s supercharged Javelin Special at bay.

By 1955 Gnoo Blas had established two dates per year, one on the Monday holiday of the Australia Day weekend in January, the other on the October Labour Day holiday weekend. The January date was touted as an international meeting, with Englishman Peter Whitehead in a four-cylinder 3-litre Ferrari, expatriate Australian Tony Gaze in a similar car, B Bira with a 2.5-litre Maserati, and New Zealanders Zambucka and John MacMillan, the latter in a supercharged 2.9-litre Alfa Monoposto. Bira’s Maserati threw a rod after just three laps of practice, while his spare OSCA suffered a scavenge pump failure, dumping its oil all around the circuit. Ian Mountain, following in his Peugeot Special, hit the oil and careered off the road, killing himself and injuring several spectators.

Whitehead took the main 27-lap South Pacific championship from Brabham’s Cooper-Bristol, recording 149mph through the flying quarter-mile on Hospital Straight. On the October date, some degree of cooperation saw Bathurst run on the Sunday, with the survivors decamping to Orange on the Monday. The feature event, the 20-lap Gnoo Blas Trophy, went to George Pearce in his Cooper-MG.

Partial resurfacing on some of the badly cut-up corners, the relocation of the pits to the inside of the circuit and other improvements helped to quell the grumbling about Gnoo Blas’s shortcomings, and the grandly-titled South Pacific Road Racing Championships took place in January 1956. The 27-lap event for Racing Cars went to Melbourne car dealer Reg Hunt in the newer of his two Maseratis, from the Cooper-Bristols of Brabham and Kevin Neal. Displacing Zambucka’s dubious lap record, Hunt was credited with 2min 17sec and instated as the circuit’s official fastest man.

In the face of stringent new laws governing safety measures at all motorsport venues in New South Wales, Gnoo Blas went into temporary recession while much work was done in the areas of crowd control. It reopened on January 27 1958 for the South Pacific Championships, attracting Jack Brabham and the latest 1.7-litre Cooper-Climax, Stan Jones in his 250F Maserati, Ted Gray in the home-brewed Corvette-engined Tornado and Len Lukey in the ex-Reg Hunt Cooper-Bristol. Gray and Brabham were hard at it immediately, Gray taking the lap record down to 2min 15sec — a real 100mph lap this time — before the Tornado ran out of puff, leaving Brabham with a healthy lead over Jones. In the five-lap handicap that concluded the meeting, Brabham carved chunks off the record to leave it at 2min 12sec — 102.2mph.

Brabham was lured back to Orange in January 1959, bringing with him a works 2-litre Cooper-Climax. Not surprisingly he won the main South Pacific event from Doug Whiteford’s Maserati 300S and the Ferrari 555 Super Squalo of Arnold Glass, but torrential rain spoiled any chance of record laps. By now the Australian motor racing public’s interest was increasingly taken by touring cars, and the arrival of David McKay’s 3.4-litre Jaguar meant that the Sedan Car Championship attracted at least as much attention as the main event. McKay duly dusted off the opposition, mainly Hoidens, and set the scene for a much bigger win one year down the track.

By 1960 the Australian Touring Car Championship had been established as a one-race contest, and Gnoo Blas got the nod to run the inaugural event. In an eventful race, in which all three front-running Jaguars spun, McKay’s Jag 3.4 overhauled the sister car of Bill Pitt two laps from the end of the 75-mile event for McKay to become the first Australian Touring Car Champion.

But it marked the end of Gnoo Blas as a frontline circuit. Two more meetings were run, but the draconian New South Wales Speedway Act, which required safety fences to shield all spectator areas, was being rigidly enforced and there was no way the circuit could comply without major money being spent. In the wake of Jack Brabham’s dual World Championships, Australia went motor racing-mad and new purpose-built circuits sprang up everywhere.

It was the beginning of the end for the big, old-style public road circuits, and Gnoo Blas was one of the first casualties, holding its last meeting in 1961. The outright circuit record was left in the hands of Jon Leighton (Cooper-Climax) at 2min 7.4sec, an average of 105.2mph, set in October 1960, while Reg Hunt’s flying speed of 161.8mph in his 250F in 1956 was never bettered.

Nowadays the road surface of Gnoo Blas is considerably better than it was 50-odd years ago, but traffic islands blight the corners formerly known as Windsock and Speet’s. The area inside the northern end of the circuit, which encompasses the old pit area and was originally an aerodrome, is now called Sir Jack Brabham Park. The local sporting car club holds a reunion here every year.

Leaving the old starting grid, the road crests a slight rise before sweeping downhill through what would have been a quick left-hand curve. Then it’s a hard brake for Mrs Mutton’s Corner — a narrow right-angled bend. This is followed by two crests, the second of which contains a very fast right curve (Connaghan’s Corner) leading downhill over a small bridge. This section, known as The Sweep, was the most challenging part of the course, and the only real bends apart from the squared-off corners common to public road circuits. After The Sweep it’s a long uphill climb before braking hard for what was Brandy Corner. This is the only part of the track that has changed from the original layout a new section of highway bypasses what was a four-way intersection.

The old road, complete with its quaint white-posted bridge, is still there, though now partly reclaimed by nature. Hospital Straight (which was renamed Total Straight in 1958 after the French oil company paid £3000 to upgrade safety facilities) begins with a long right curve past the hospital and a golf course and finishes 1.3 miles later with the 110-degree Windsock Corner. A short squirt leads you to Speet’s Bend and back to the start/finish area.

We drove the circuit in the Reed Special, the car that won the 1951 Australian GP at Narrogin in Western Australia. George Reed, from Bathurst (a mere 2500-mile drive away!), had two self-built short-wheelbase specials with Ford V8 engines ready for the event.

Reed drove one, with Warwick Pratley in an earlier version. It was Pratley whose car lasted to win the event on handicap, and the GP-winning ‘Skate’ continued to ply the circuits until it was destroyed in a crash. Around 1990 Reed assisted mechanics at the motor workshops of Bathurst Council to recreate the car, which was then donated to the National Motor Racing Museum located beside the famous circuit at Mount Panorama. The specification used the original highly modified 1926 Essex Six chassis, which was reversed with the rails running over the front axle and beneath the rear axle; a 1940 239 cu-in Flathead motor is coupled to a ’39 Ford gearbox and diff. George Reed, who in 2006 is approaching his century, was not only a keen driver/constructor but a prolific photographer, so there was plenty of visual reference for the reconstruction. The ‘Red Car’ is a comfortable road car as well as being a spirited performer, and it makes regular appearances at events such as the annual Gnoo Blas Classic Car Show.

Both car and circuit revive a long-lost period in Australian motorsport history.

Rockingham Speedway First car race 2001 Last car race 2018 Lap record 24.908sec, Jimmy Vasser, Lola B02/00, 2002 Rockingham, the first banked oval circuit to be built in Britain since…

Langhorne, a one-mile dirt track speedway in Pennsylvania, was a place that drivers both feared and respected, the ultimate challenge for the bravest of the brave. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gKK06hcdVao “No circuit scared…

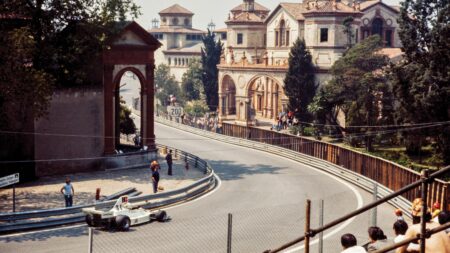

As street circuits go, Montjuich Park had everything: the climbs and hairpins of Monaco (and then some), with fast-flowing sections demanding inch-perfect precision. First used for car racing in 1933…

A mountain circuit around two extinct volcanoes with 50 corners and just one brief straight – surely not a grand prix venue? Yet that was Charade, scenic but challenging, clinging…

You’ll need a full day at the wheel to drive from London to Zandvoort even with the tunnel and the continuous thread of motorway that now lies between Calais and…

Get it stopped. Stuff it in to the apex. Nail it on the way out. Medium-speed, high-downforce is the current Formula 1 way. Flat out is flat out is flat…

The most beautiful racing circuit in the world — that was the standard boast. Subjective in the extreme, for sure, but standing atop the valley slopes that tumble to the shores…

Shielding my eyes against the sun, I gaze back along the straight. Stretching to the horizon is a silver-black band of Tarmac spray-gunned with can and shrouded by converging lines…

Senna on a hot lap. Fangio steering with the throttle. Bellof lowering the Nordschleife’s lap record, from a standing start. An awakening Chevy stock-block. These are the motor-racing things that…

All we have to go on is a crumpled circuit map that magazine editor Paul Fearnley pressed into my hand back in England. That and the knowledge that, each year…

It was what the French call ‘Un été de la Saint-Martin”— an Indian Summer. Across continental Europe the weather had been hot, oppressive. During our night time run into France…