Anyway, who the hell was Repco to think it could build an F1 engine?

In fact this Melbourne-based company was a typically astute Jack Brabham choice. Formed in the 1920s to make replacement parts for imported cars, by the ’50s it was huge, boasting manufacturing and technical agreements with leading car manufacturers in Britain, Europe and America. It wasn’t exactly Jack’s big secret – the early production racers that emerged from his New Haw premises were marketed as Repco Brabhams – but he had been carefully husbanding this relationship since 1950, his formative racing days Down Under. Repco made him special parts for his World Championship works Coopers, and in 1961 mechanic Tim Wall ran Jack’s privateer car out of Repco’s Surbiton warehouse, the first home of Motor Racing Developments (MRD), the company founded by Jack and Ron.

Racing was a small but prestigious part of Repco’s empire. Not every member of its board was convinced by motorsport, but chief engineer Frank Hallam was able to talk them round. It helped that double World Champion Jack was a regular headliner in the winter series of races in Australia and New Zealand, using Repco-prepped Coventry Climax FPF four-pots. And that’s how the new engine project was initially addressed: as a bid to maintain this market in the face of the new 2.5-litre Tasman Cup (from 1964) and dwnidling FPF spares.

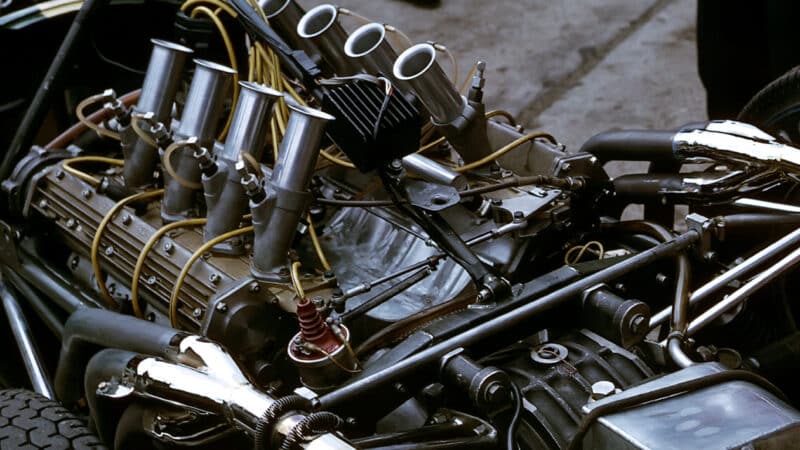

1966 Repco V8 in BT20. It would be fully bespoke in ’67

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

In was during the 1964 Tasman series that Jack suggested a V8. Money being a definite object, a proprietary block was sought: Oldsmobile’s liner-less aluminium F85 had recently been shelved, at huge cost, by GM; Jack dusted off a trial dry-linered version, bought it (for around £11) and shipped it to Repco. It was a very useful building block – but it was only that. The base motor featured overhead valves operated by willowy pushrods actuated by a camshaft in the centre of its vee; hardly ideal for a high-revving racing engine. There was a lot of work to be done – ultimately, perhaps, more than if the engine had been completely bespoke – but Jack was persuasive, and Repco put freelancer Phil Irving on the case.

Born in Melbourne in 1904, Irving had gained global status either side of WWII as chief engineer at British ‘bike firms Vincent, HRD and Velocette. Fluent in every part of the process, from drawing board to dyno, he had been mulling over V8 designs long before he was commissioned. His first prototype, a 2.5-litre for Tasman racing, ran, on carbs, in March 1965. It was too late for that year’s Tasman Cup – a Repco V8 would score only one victory in this series, Jack’s BT23A winning the final round of 1967 at Longford – but it was in plenty of time for what Jack had always considered its primary purpise: F1.

“Phil would start mid-morning and work deep into the night, smoking non-stop”

When in 1964 Coventry Climax announced that it would pull out of GP racing at the end of ’65 rather than build a full-shot 3-litre, the rush was on to find alternative power sources – except at self-sufficient BRM and Ferrari. Jack “knew by 1964 that Repco was coming” and craftily installed Irving in a rented South London flat during the summer of ’65…

“Phil would start mid-morning and work deep into the night, smoking non-stop,” recalls Tauranac, who advised him on installation requirements. “I had no problem with him, but he had his own ideas and wouldn’t always stick to the pre-arranged plan agreed with Frank Hallam. In fact Frank came to England during the year to get the project back on track.”

The F1 engine retained Irving’s heads – mirrored to fit either bank, thus easing the spares situation – with two parallel valves per cylinder, chain-driven single overhead cams and wedge-shaped combustion chambers. It also kept Laystall’s flat-plane crank, lightened and balanced, Daimler V8 conrods (sourced by Jack £7 a throw!) and the 3/16in diaphragm that stiffened its bottom end. By reverting to the F85’s original bore (88.9 instead of 85mm) a 2994cc engine was produced giving, on Lucas injection, 285bhp at 8000rpm. Entitled 620 – the hundreds referred to the blocks, the tens to the heads – this 90-deg unit was frugal (7mpg), light (330lb) and compact (21in across the heads).

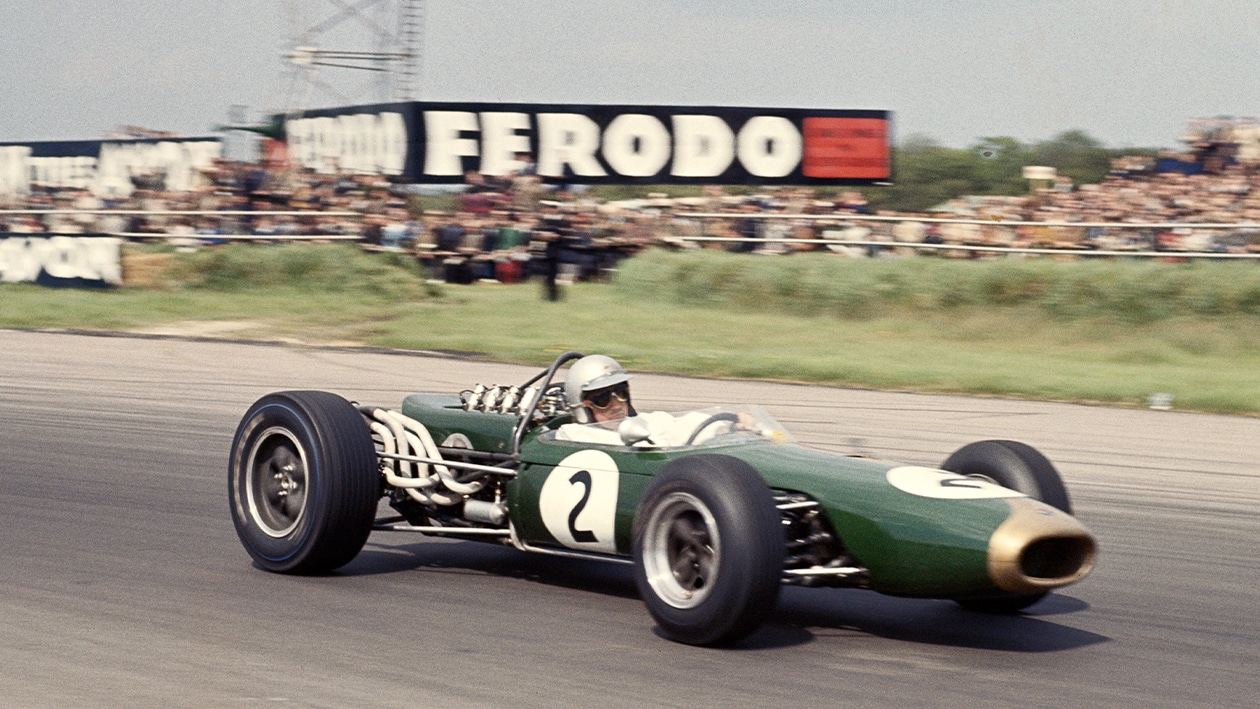

Brabhams on the front row at 1966 British Grand Prix

Don Morley/Getty Images

Its narrowness was one of its fundamental parameters: Jack wanted it to fit an existing chassis. Which was a good job, because Tauranac was keen to design a new F1 car, being unhappy with the direction MRD had taken.

“At the end of our first year of F1 Jack said he would like to run his own team, the Brabham Racing Organisation,” says Tauranac. :The idea was that he would become a customer of MRD and pay £3000 per car. After three seasons of no direct involvement, no feedback and no money for development, I had lost interest. That’s why, at the end of the 1.5-litre formula, I said I didn’t wish to build any more.”

Fortunately this cleared the air; a new agreement was drawn up and Tauranac was back onside – “I played a much bigger part from 1966 on” – even though BRO had been ‘physically’ ring-fenced and moved from MRD’s overcrowded New Haw HQ to Guildford. “Jack and I had the partnership back to the way we had originally planned it.”

Jack: “I never actually fell out with Ron, but we had to make sure the F1 side was going to work. My driving had gone stale, but with Repco behind me I was fired up.”

Tauranac (left, with Brabham, was a key player in success

GP Library via Getty Images

The whole F1 outfit was re-energised. Which was a good job. because it was November: the South African GP was looming, and a Repco V8 of any description had yet to run in a chassis of any type.

The BT19, unusual for Brabham in having oval tubes around its cockpit area, had originally been designed for Climax’s never-to-race 1.5-litre flat-16. Now it was pressed into service for a new era. “It was probably chosen because we had one available and time was short,” admits Tauranac.

Ron would soon begin work on the BT20, based on the BT11. With an inch-longer wheelbase than the BT19 (7ft 9in), a stiffer frame and 15-inch front Goodyears instead of 13s, Denny Hulme would use it to finish third on its debut, in France. Jack, though, stuck with BT19, his ‘Old Nail’. It did him proud. Not at Monaco – its gearbox jammed after 17 laps – but at Spa, Reims, Zandvoort, Brands Hatch and the Nürburgring. Spa provided the consolidation, a circumspect fourth after a huge moment in the first-lap rain; Reims, on July 3, provided the breakthrough.

Jack with champagne after winning ’66 French GP

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

Lorenzo Bandini, Ferrari’s ersatz number one, made an early break, albeit with Jack clinging tenaciously to his tow. When this was eventually broken by dithering back markers, Jack, confident that the Italian would keep on pressing, decided to nurse his car and await developments. They arrived on lap 32, a broken throttle cable stranding Bandini at Thillois hairpin. He jury-rigged it using a wire from around a straw bale – but Jack was long gone, sweeping past fields of golden corn, deep in Champagne country, towards the maiden eponymous car/driver GP win.

“I’d had confidence in the project from the start,” says Jack. “But after beating Ferrari in this race my sights were definitely on the championship.” It was his first top-line victory since 1960. He’d recently turned 40. Life was beginning all over again.

“Jack and Ron were great teachers. They both knew their stuff”

“We had a few bottles of champagne to celebrate,” says Hughie Absalom, this Anzac-dominated team’s ‘Welsh Pom’ and Jack’s number two mechanic. “Everything had suddenly clicked. We had more control with Repco than with Climax. The latter used to appear at our door and we’d drop it in a car, run it and, if it broke, take it out and send it back. The Repcos arrived in packing cases as complete units, but it was us who stripped and rebuilt them. We had some problems early on, but after that it went remarkably smoothly.

“We were a very young team, but Jack and Ron were great teachers. They were very different – Ron more abrasive, Jack more open to suggestion – but they both knew their stuff. Jack understood his car in a way that today I only see from Michael Schumacher. I learned more at Brabham than I did during my subsequent spell at Lotus.

Jack wouldn’t retire again until Italy in September, oil lost through a loose inspection plug forcing him out of an early lead. As it turned out, however, he had already done enough, securing the world title while he sat on Monza’s pit counter. It was too low-key for some…