But by this point Audi Sport was not just under pressure on the stages. Audi had staked its reputation on the Quattro concept and it would mean a major backtrack in marketing terms to admit that front-engined wasn’t good enough for competition. And although Piech gave tacit approval for the project, he didn’t exactly go running to the VW-Audi board with a set of blueprints. Accordingly the car would have to be developed under previously unseen levels of security.

To achieve this Gumpert turned to the Cold War — or communist Czechoslovakia to be precise.

Situated nearly 200 miles south of Prague and conveniently behind the Iron Curtain, the Desna test facility near Zlín had originally been conceived for Porsche, but with Audi ready to bankroll it further it became the unofficial home of the mid-engined Sport Quattro. Cars shipped in crates marked ‘Kenya test’ — to keep even the factory spies and mechanics guessing — began turning up in 1985, often alongside what would become the fully-winged Sport Quattro E2. And in return for the hard currency the locals constructed permanent workshops and obeyed police instructions to keep quiet. “I had a few good friends there,” says Gumpert, “and the moment we went across the border we knew we were safe. We knew there wouldn’t be any photographers or journalists hiding in the bushes.” His confidence was well-placed — the Desna shots printed here (right) were taken by a local and did not surface until last year.

The mid-engined cars that tested looked nothing like the Group S Prototype — they resembled regular Sport Quattros, albeit with a tell-tale duct in the roof for engine cooling. Many of the mechanicals, including the five-cylinder motor, were lifted straight from the regular car. But Gumpert recalls: “It was pretty much quicker straight away. The engine was just as strong, of course, but the handling was much better just because of the weight distribution. We knew we had more work to do, but it did not take too many tests before we felt it was ready to allow Walter Röhrl behind the wheel.”

Röhrl, the 1982 world champion, was by now the centre of Audi’s rallying activities and, even though he had not driven the car at Desna, plans were quickly put in place for him to get a first run on a stretch of gravel road near Salzburg in Austria. Trouble was someone had tipped off the press and the media were crawling over the proposed site by the time the test team arrived. Petrified of blowing its thin veil of secrecy, Audi turned its trucks around and moved back across the border into Germany, where it found a few miles of (open) asphalt road in Bavaria.

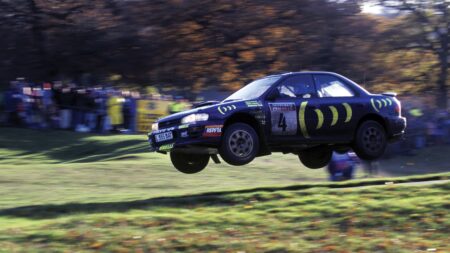

Front profile is more kit car than rally supercar

Audi

There Röhrl would get his only taste of mid-engined Audi power. “I could tell straight away how much better it was,” he recalls, smiling. “The road was just old asphalt – normal second-category roads, with a bit of twisty stuff and some fast sections. The impression I got was really good – as good as the Quattro Sport E2 straight away, in fact. Many times I’ve had cars which you have tested for 40 days to get to the same level as the old one. But this one was really impressive. The engine felt the same because it was just out of the Sport Quattro E2, but the handling made all the difference for me. It was so much better in the twisty stuff and it didn’t get twitchy when the corners got faster.

“I remember the road wasn’t too far back over the German border. They were so keen for me to try the car that they found the bit of open road, took out the car and we went for it. Nobody was expecting that, of course. But then after 40 or 50 kilometres I came over a brow and saw the police. I stopped and asked them, ‘Why are you here? Did you know I was coming along this road?’ and they said, ‘No, we didn’t know in advance. But we’ve heard you coming for the last 10 minutes!’