Hocking was an instant hit on privateer Nortons, and MZ gave him his first works ride in 1959; he won first time out on its 250 two-stroke at Kristianstad in Sweden. He won at Dundrod, too. And all-conquering MV came a-calling. Its team leader John Surtees was making noises about switching to four wheels — he would successfully mix and match codes during ’60— and Count Agusta needed a new talent to pick up the torch. He chose wisely. Hocking finished runner-up to MV’s Carlo Ubbiali on the 125s and 250s and to Surtees on the 350s in his first year with the team, and leapt seamlessly onto its number one saddle when Surtees, a seven-time champ with MV, went cars for good in ’61.

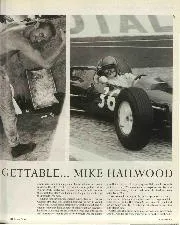

“Gary was a very serious competitor,” says Surtees, “very determined and more interested in the technical side of things than Mike Hailwood. I felt happier leaving MV in the knowledge that he would be there to guide them.”

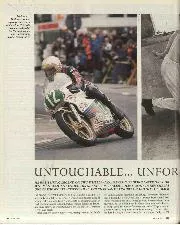

Hocking won 12 times in 1961, including seven of the nine 500cc GPs he contested, and secured that and the 350 title. However, the late-season arrival at MV from Norton of Hailwood — who promptly ended Hocking’s 500cc domination with a win at Monza — and the increasing threat from Honda indicated that a more testing ’62 was on the cards. Hocking’s win in the year’s Senior TT proved that his talent was still up to it; but his heart was no longer in it He flew straight to Italy to tell Agusta that he was retiring forthwith.

Surtees saw Hocking as the ideal person to take over for him as lead rider at AV Augusta

National Motor Museum/Heritage Images/Getty Images

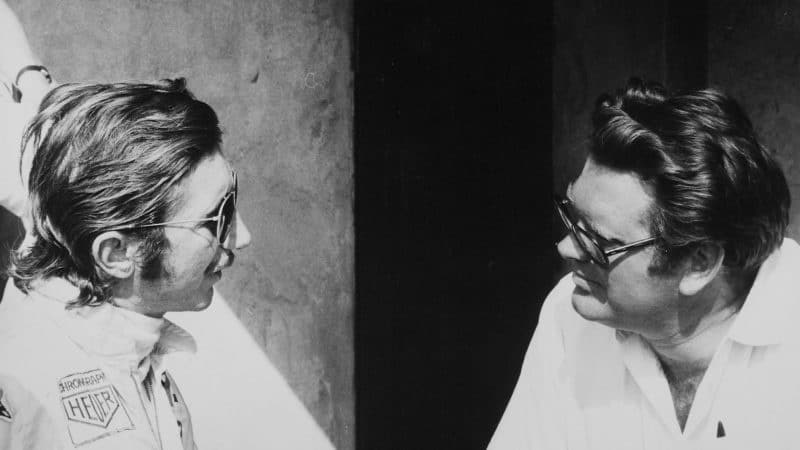

“Gary asked my father for advice about getting started in cars,” says Tim Parnell. Dad Reg was adamant that good biker rider equalled good car driver — Surtees was capably heading up his Lola GP squad — and Hocking seemed to be cut from the same cloth. “I had injured myself in 1961 and was out of racing that year,” continues Tim, “so dad offered him my Lotus.” The four-cylinder 18/21 was outdated in Fl ‘s new V8 era, but it would do — for now.

Hocking took the Alan Smith-prepared car to Mallory Park and planted it on pole for the August Bank Holiday Formula Libre race. He led it too, only to be denied a win by an engine failure. Tim was bowled over: “I have never seen anybody compete so fiercely and competitively in their first-ever car race — except perhaps John Surtees. They’re a different breed those bike boys. It was raining a bit and Gary was amazing in those conditions. Totally at home.

“It was a slightly tricky situation given that Dad had John on his books, but he knew that he had somebody else with incredible potential in Gary, and so he entered him in the Lotus for the Danish Grand Prix.”