Throughout Mexico, and within the racing community too, there was an outpouring of anguish, for Ricardo, a quiet and polite young man, had been well liked and highly regarded. For his family, of course, it was a very traumatic time. The father, Don Pedro, had become very wealthy, through this means and that, and spent freely on his sons, wanting nothing more than to see them high in the racing firmament. Of the two, Ricardo was regarded as the more natural driver, the future world champion; for Pedro, it seemed initially more like a hobby than anything else.

Pedro was there the day his younger brother died and the effect on him was profound. For a time he renounced racing altogether, apparently even spoke of retreating to a monastery, but in February 1963 he shared a Ferrari GTO with Phil Hill in the Daytona 1000Km — and won. Several years would pass before he committed to full-time racing, but Pedro would become one of the world’s greatest drivers. Ultimately, in 1971, there was further sorrow for the family when he was killed in a Ferrari at the Norisring.

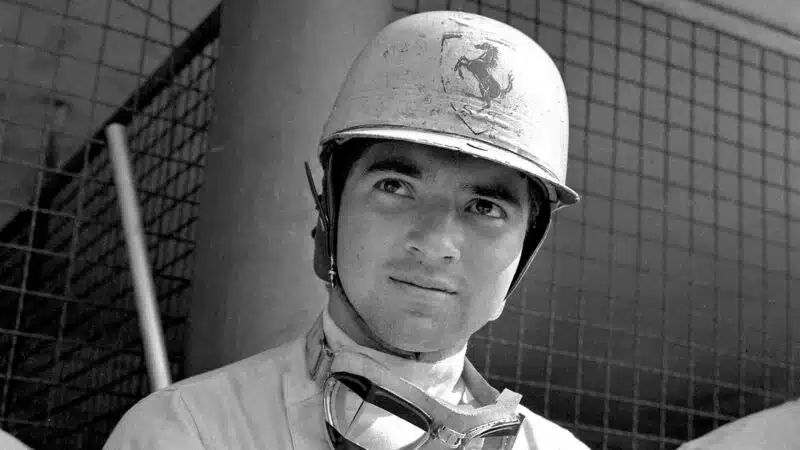

We remember Pedro now as a cool driver, the epitome of smoothness, but in his early days he was regarded as a wild man. Ricardo, by contrast, was silky with a car, apparently touched by the angels. At 15, he was racing a Porsche RS — and winning with it. The following year he was bitterly disappointed to have his Le Mans entry rejected. Sixteen, said the Automobile Club de l’Ouest, was too young.

Pedro Natalio Rodríguez (left), Ricardo Rodriguez (middle left), Pedro Rodriguez (middle right) and Luigi Chinetti (right) at 1958 Le Mans 24 Hours

Getty Images

Pedro, all of 18, did go to the Sarthe in 1958, however, sharing a Ferrari with Jose Behra, brother of Jean, and in ’59 Ricardo got to partner him in an OSCA. Thereafter, they frequently drove together, usually in Ferraris for Luigi Chinetti’s North American Racing Team.

If Ricardo was usually a bit faster, his style had by now begun to change. Decidedly more wild and unrestrained than before, he worked his cars very hard and had a lot of accidents. He was, murmured some contemporaries, rather too brave for his own good.

Chinetti, though, was a fundamental believer and reckoned that in time this side of Ricardo’s racing personality would be calmed. Always a man with the car of Enzo Ferrari, he missed no opportunity to sing the praises of both Rodriguez brothers, and the wily Commendatore offered Don Pedro the opportunity to buy them into the factory team. Ricardo jumped at the opportunity, but Pedro decided against it, still not certain he wanted to be a pro.

In the 1950s and ’60s, it was Ferrari’s custom to enter extra cars for the Italian Grand Prix, and in ‘61 no fewer than five were on hand: for world championship protagonists Phil Hill and Wolfgang von Trips, for Richie Ginther, for Giancarlo Baghetti — and for Ricardo Rodriguez.

Four Sharknose Ferraris line up at 1961 Italian Grand Prix — a 19-year old-Rodriguez was on the front row

Getty Images

To make your GP debut at Monza in a Ferrari — at 19— is to face as much pressure as racing can exert, and the consequences, given Ricardo’s outlook, could have been disastrous.

Driving an older car than his teammates, he qualified second, just a tenth slower than von Trips.

As it was, he retired early from a tragic race: von Trips and several spectators were killed in an accident on the second lap. Enzo, as ever in these circumstances, was branded by the Vatican and the earnest Catholic press as a killer of young men; as usual he rode out the storm, announcing a full racing programme for 1962, with Rodriguez as one of his drivers.