Instead, Tim Parnell and Bob Anderson ran the cars as part of privateer efforts during 1963, and scored 19 points less than in 1962 – i.e. none.

And instead, FoMoCo came a-calling at Lola’s Bromley base, wowed by free-thinking Broadley’s midengined GT racer, the GT40, née Mk6. Le Mans, Indianapolis and increasing customer demand, all of them far more lucrative than the Formula 1 of the period, thereafter blunted any GP aspirations Broadley held.

Truth be told, it had never been his be-all and end-all. Truth be told, it was near-neighbour and admirer Surtees who had kick-started Lola’s F1 programme; Broadley had been too busy fretting over his threadbare finances to consider it. After a season going nowhere in an off-the-peg second-string Cooper, though, Surtees knew his career needed new impetus, needed the benefit of a focused works effort. By the summer of 1961, his intensity and drive had brought finance house Bowmaker, experienced principal Reg Parnell, and the untested but indubitably talented Broadley together. And before the season was out, he would be sorting Lola’s F1 prototype.

The final piece of the puzzle was meant to be Coventry-Climax’s 90-degree V8 FWMV, which arrived just in time for the 1962 Dutch GP on May 20. Fitted with a four-cylinder Climax, Surtees’ Lola had regularly been best of the non-V8 rest in early-season ‘sighter’ races, sharing fastest lap with the date-with-destiny-bound Lotus 18/21 of Stirling Moss in Goodwood’s Glover Trophy. But the V8 was not the immediate panacea it had been hoped.

Surtees blasts away from pole at the 1962 Dutch Grand Prix

Grand Prix Photo

All looked well from the outside, Surtees planting the Mk4 on pole for its world championship debut. But, from within, he was unhappy with its unpredictable handling. The altered mountings demanded by the V8, and its extra power, had revealed too many spaces in the Mk4’s frame. There were other cracks in the veneer, too: only the official timekeepers had ‘spotted’ Surtees’ out-of-the-blue banzai lap; and Broadley had seen the future in a sand-blasted paddock the paradigm shift that was Chapman’s 25.

The race was a more accurate indicator, Surtees dropping to fourth at the start before skating off the road on lap nine at a 125mph-over-brow right, his progress arrested by some of John Hugenholtz’s newfangled catch-fencing and, beyond, a crumple zone of sit-up-and-beg bicycles so beloved of the Dutch.

The cause of the crash? The left-front wishbone had broken at the first time of full-tanks (26 gallons) asking. Lola had a lot to learn. But Lola had very little time.

The car was nicely engineered, Broadley going his own route on front suspension, long trailing arms transferring some loads back into the cockpit area it’s just that he had underestimated those loads. And others. This only became apparent at Spa.

Surtees slips behind Hill and Gurney at Zandvoort, before retiring soon after

Grand Prix Photo

The previous weekend, Surtees had won the 2000 Guineas F1 encounter at Mallory Park, leading the 75-lap Whitsun race from start to finish, despite the presence of Jim Clark‘s 25 (an early retiree) and Jack Brabham‘s stopgap customer spaceframe Lotus 24 (a distant second). Spa, though, was a daunting and wholly different matter: Surtees was struggling for consistent handling, and for a solution. The penny dropped, though, when a corner was jacked up so a new Dunlop R5 could be bolted on. The other three wheels stayed squarely on Spa’s terrafirma.

Which is why, from where I am sitting, ticking-over Climax vibromassaging my shoulders, all appears to be triangulated. Lola had flexed its muscles, stiffened its resolve, buttressing the cockpit area with a host of extra tubes which must be much stronger than their runny-custard hue suggests.

The proof of this pudding was the non-championship, but fullshot entry, Reims GP in July ’62. Surtees led comfortably. Until a valve spring broke at half-distance.

One week later, he was menacing in second, glued to Graham Hill’s tail, in Rouen’s French GP, when carburation problems sent him, fits and starts, into the pits on lap 14. He would eventually struggle home fifth, wedged permanently in fourth gear.

It was clear, though, that new boys Lola had, impressively, caught and overtaken Cooper, Porsche and the Lotus 24 on the development front. Only the purposeful 25 and powerful P57 lay between it and victory. But this proved a gap it could not breach.

At point-and-squirt Aintree, Surtees chased the laidback Clark for the entire 75 laps; at plunge-and-swoop Nürburging, it was a steely Hill (and leaden Walter) who thwarted him.

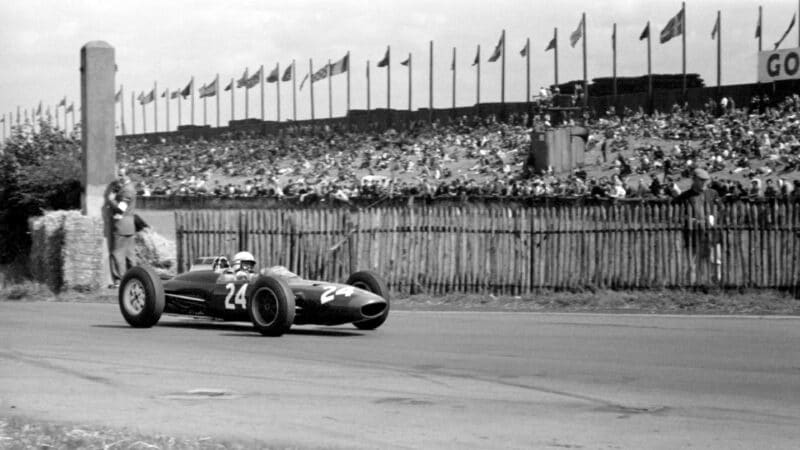

John Surtees aboard the Mk4 in the 1962 British Grand Prix at Aintree

Grand Prix Photo

And that was as good as it got. Put simply, Lola was not at the front of overstretched Coventry-Climax’s queue (the company had yet to commit to the 1963 season); Clark was its number one man as he strove to beat Hill to the title. So, maddeningly, when Lola had had the power, it did not have the chassis; and now, when it had the chassis, it did not have the last edge of power, nor the first word in reliability.

Surtees was third in the updated Mk4A, battling tooth and claw with Richie Ginther‘s BRM at Monza, both of them a good way behind leader Hill, when his Climax cried enough, on lap 42. He was running third, too, in South Africa, a long way behind the all-encompassing tide showdown between Clark and Hill, when another Climax croaked, this time after 26 laps of East London. In between times, there was a 19th-lap terminal oil leak at Watkins Glen, a GP weekend coloured by a practice wreck triggered by a broken steering link. There was no catch-fencing or bicycles this time, just a big tree, and Surtees was lucky to escape with a jarred back. He would start the race from the rear of the grid in teammate Roy Salvadori‘s car.