Nor did its design lack innovation. As Murray points out, “it was the first F1 car to use carbon-fibre in its tub and though it was also part aluminium, we used carbon-fibre in the car’s structure two years before McLaren.”

That, however, was not the BT49’s secret weapon, the reason which made the car the class of the F1 field and gave Brabham its first driver’s title since 1967. The ace up its elegant sleeve, says Murray, was downforce. “It just had more of it, more than any other car out there and it all came from the ground effect. We ran the car with no front wing at all and scarcely any at the back. It all came from under the car and it generated more pure downforce, I think, even than the Williams. When we had to run a flat bottom, we lost two-thirds of the downforce in an instant.”

Its engineering simplicity did, however, play a key role. “It was the most reliable car of its era. In Nelson’s championship year he never failed to finish through mechanical failure.” The books support this: fifteen starts, ten finishes, four accidents and one mechanical failure when his engine blew at Monza on the last lap relegating him to sixth.

The elegance and simplicity Murray refers to is not simply beneath the skin. To my eyes, the Lotus 79 is the only one of its contemporaries with a claim to greater beauty. It’s at its best seen from dead head-on, where the downward curve of its gently sloping side pods have elements of Concorde’s wing profile. The nose sharpens to a defiant point, there is nothing to interfere with the airflow over the body save the mirrors and driver’s head while the Parmalat livery is one of the smartest of all.

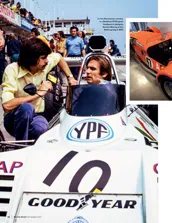

Beautiful, however, does not mean big in this case. The BT49 was the first GP car Murray had designed which was unable to accommodate his six foot four frame. “Our big drivers like Watson had all left the team so I chopped three or four inches.out of the monocoque. How on earth did you get in?”

Simplicity was key in Murray’s design – as well as huge downforce

Grand Prix Photo

By removing the seat and bodywork that’s how. The elegant body is, in fact, all one panel and lifts off easily. I could then just about cram myself into the tub, rear seat-belt mounting points dug deep into my back and strap myself in before the bodywork was replaced. If I’d had an accident or had to get out of the car in a hurry for any reason at all I would have stood no chance at all. Someone plugged in a starter and, with a whoop and a bang, eye-wateringly loud through a helmet, balaclava and ear-plugs, the Cosworth fired up.

This DFV sounds different to most hammering around the track, reflecting its extreme state of tune. It’s note is more melodic, smoother and exciting than usual. Giles cautions me never to let it run below 6000rpm, suggests I shift at 10,500rpm to give myself a little room for error (he takes it to 11,200rpm) and advises that it only really gets going above 8500rpm.