I was still a year away from working in motor racing, and had gone to Monaco on a Page & Moy trip, reserving myself a front-row seat in the grandstand at the old Gasworks Hairpin, the final corner of the lap and thus now the final corner of the race. As Jack Brabham and Jochen Rindt went into their last lap, they were just over a second apart. I double-checked the settings on my Canon FX, and waited.

Piers Courage‘s hobbled de Tomaso was the first car to come into sight. In his position, it was difficult to know how to keep out of the way, for the stretch down to Gasworks was a long left-hand curve, and the fastest line was out to the right. A slower car would therefore hug the left-hand wall which was fine until it reached the braking area for the hairpin, for there a car travelling quickly would chop across to the left, to take the best line for the hairpin.

For Brabham, Courage was in precisely the wrong place at precisely the wrong moment. What Jack should and, ordinarily, would have done was duck in behind the de Tomaso, and accelerate by at the exit of the hairpin, for while Rindt now had him in his sights, he was not close enough to try an out-braking move.

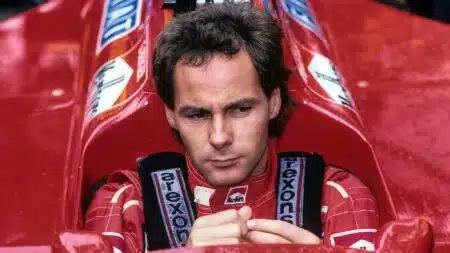

Jack Brabham wielded a comfortable lead until disaster struck

Getty Images

An inspired Jochen, though, would unnerve anyone, and in the circumstances it was perhaps not surprising that Brabham, for all his experience, felt he had to get by Courage before the hairpin; that being so, he steered to the right, off the regular line.

No one had been there all weekend, and the track was dirty and slick. When Jack put the brakes on, his car despite being on full right lock slid straight on, thumping into the barrier at my feet.

“If Jochen felt there was no chance of winning, often he just went through the motions” Colin Chapman

On the approach to the corner, he and Piers had filled my viewfinder; now, as he threw the race away, so I did the same with the camera. Not my forte, motor racing photography…

The race had started in a straightforward fashion, with front row men Stewart and Amon running 1-2 in their agricultural March 701s, followed by Brabham, Ickx‘s Ferrari, Beltoise‘s Matra, Hulme‘s McLaren and Rindt.

In truth, Jochen approached the race with something close to indifference. “That was the way he was sometimes,” Colin Chapman told me years later. “That was Jochen. If he felt there was no chance of winning, quite often he just went through the motions…”

Rindt had been in a negative frame of mind even before practice began, for Chapman’s new wonder car, the 72, had proved anything but that in its first couple of races, and Colin had accepted that some of its innovations had to go. While the redesigns and modifications were undertaken, Lotus had to revert to the venerable 49 for Monte Carlo, and Jochen felt the car no longer had a prayer.

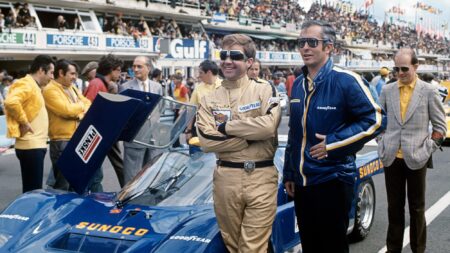

In an older car, Rindt felt he didn’t have a chance…

Grand Prix Photos

It looked that way during practice. In the first session, on Thursday, he was sixth, but his time 1m25.9s was almost two seconds away from Stewart; in the second, run at crack of dawn on Friday, it poured down, and Jochen, disinterested, was slowest of all; in the third, on Saturday afternoon, he felt queasy, and was two seconds off his Thursday time.