1974 South African Grand Prix race report

Carlos Reutemann claimed his first win of 1974 in his Brabham

Motorsport Images

A popular win for Reutemann

Kyalami, March 30th

After a two-month break following the two South American Grand Prix races, during which the Brands Hatch Race of Champions conveniently took place, the World Championship series was resumed at South Africa’s Kyalami circuit near Johannesburg. A degree of uncertainty had surrounded the fate of this race for a few months following the South African Government’s ban on all forms of motoring sport which use pump petrol, and at one point it seemed as though the race would not take place at all. Fortunately, the circuit and race are under the direct control of a very determined man called Alex Blignaut, primarily a very astute businessman but also basically a racing enthusiast for he owns Tyrrell 004 and enters it with the assistance of Embassy sponsorship in local races for his friend Eddie Keizan. Blignaut wanted his race to go ahead, and some subtle hints that the circuit could be sold as a housing estate eventually made the necessary approval forthcoming from the authorities, although the date had to be delayed until the end of March.

Pre-race testing was allowed on a couple of days during the previous week, these sadly being highlighted by a fatal accident to UOP-Shadow team leader Peter Revson. Testing DN3/1A, the car in which he had taken sixth place in the Race of Champions the Sunday before, Revson crashed on the sweeping downhill right-hander called Barbecue just before the end of the main straight. The accident occurred at a point where drivers are changing from third to fourth gear and evidence suggests that the pin holding the front left wishbone to the upright broke and sent the car straight on into the steel barrier at almost ninety degrees. Denny Hulme, Emerson Fittipaldi, Graham Hill and Eddie Keizan all stopped to help extricate the American driver from the wrecked Shadow, but the impact inflicted fatal injuries on Revson and there was nothing they could do to help. It was significant, however, that a large number of drivers expressed a new apprehension over steel barriers and their potential dangers after this accident. There was no need for such barriers at this point, and modifications to the circuit took place before official practice started, a triple-layer catch fence replacing the barrier at the scene of the accident. Remembering how both Stewart and Cevert were saved from injury by catch fences at Crowthorne Corner last year, one could not help feeling this was another case of “shutting the stable door after the horse has bolted” and can only nurture the vain hope that the latest victim of these barriers will at least provoke some less muddled thinking over the question of safety facilities.

In the wake of this disaster, the Shadow, team withdrew their second car DN3/2A for Jean-Pierre Jarier, but there was still a full entry from the other Grand Prix teams, their numbers supplemented by several ambitious local entries using second-hand Formula One machinery. Heading the list of entries, both cars taking place in their very first race, were Colin Chapman’s latest Lotus creations for Ronnie Peterson and Race of Champions victor Jacky Ickx. The Swede was allocated R9, the car which had been displayed to the Press at an elaborate John Player Press conference in February, while Ickx had a brand new chassis R10. One of the most interesting technical points of the car’s original design, the Automotive Products developed electric clutch system, had been left off Ickx’s car for although the Belgian had tried it and liked it on his road-going Lotus Plus 2, he preferred to stay with conventional controls on his racing car. Peterson’s Lotus retained the automatic clutch system, and both cars had their nose sections mounted on small extensions so that air could be drawn from beneath, through the slight gap at the front of the monocoque and up over the top of the body. Otherwise the cars were to the specification as originally displayed, hut Chapman hedged his bets by having 72/RR on hand as a spare and marked in the entry list as a reserve car for both his drivers.

Tyrrell designer Derek Gardner was busy back at the team’s Ripley base putting the finishing touches to chassis 007 at the time of the South African Grand Prix, so Jody Scheckter and Patrick Depailler were left with chassis 006/2 and 005 respectively to the same specification as they had run in Brazil. The Marlboro Team Texaco McLaren M23s were running in the same trim as they’d been seen at Brands Hatch two weeks earlier, and the team felt quite confident as both Fittipaldi and Hulme each have a Grand Prix victory to their credit this year and Hulme put the McLaren M23 on pole position at Kyalami last year on its very first outing. Mike Hailwood was still running that very same car under the Yardley McLaren banner, and he was feeling similarly optimistic on a circuit which he knows and likes well.

Bernie Ecclestone’s Brabham team arrived with their South American GP machines for Carlos Reutemann (BT44/1) and Richard Roberts (BT44/2), their designer Gordon Murray hoping that things might come right for the team at Kyalami, for he at least was on home soil, hailing from “just down the road” at Durban. Both cars looked absolutely immaculate and almost completely free of sponsorship stickers, a situation which the attentive observer would have seen to change after practice with the appearance of a couple of Texaco decals on the cars. It wasn’t an indication of a fresh high-powered sponsorship deal, merely Ecclestone losing a gin rummy game with Texaco’s racing public relations man who had astutely been allowed to name the stakes. It was to provide a lot of free advertising in the days immediately following the Grand Prix! Supplementing the Brabham ranks was the brown Hexagon BT42/2 for John Watson, this car now having been extensively strengthened round the front of the monocoque as well as being fitted with a revised fuel system devised to counter the pick-up problems which troubled the car in 1973.

March Engineering brought along their usual pair of 741s, both now sporting a Formula Two-type extended nose section, Hans-Joachim Stuck being the number one works driver, despite his inexperience, now that Howden Ganley has left the team to join the Japanese Maki project. Stuck came to South Africa straight from his very first Formula Two triumph round Barcelona’s Montjuich Park, while Max Mosley’s business dealings now mean that the second works March is driven by Italian Formula Two exponent Vittorio Brarnbilla. The younger of the two Brambilla brothers, Vittorio drove a March-BMW in the European Championship during 1973 in the orange colours of the Italian Beta tools concern. His sole Formula One experience is limited to a few laps round Misano Adriatic° in the McCall Martini Tecno late last year, but Beta have chosen to back Brambilla’s move into Grand Prix racing and March 741/2 now carries their distinctive orange colour and signwriting.

The works Ferraris sported minor modifications not seen on the two which raced at Brands Hatch. Regazzoni (011) and Lauda (012) now had revised cockpit sections which incorporate the cold air box for the flat-12 cylinder engine in one large piece. The front of the cowling starts further forward than on the “two-piece” design, with a more gentle slope back towards the screen over the front of the cockpit. Neither driver found them to offer any difference in terms of straight-line performance, but they did at least provide a cooling draught into the cockpit which made things rather more comfortable under the sweltering South African sun.

BRM brought along their distinctive new P201 chassis for Jean-Pierre Behoise, leaving the other two Frenchmen in this British team to rely on their “old faithful” P160s which are now in their fourth season of Grand Prix racing. The P201 looked very promising in private testing, continuing the tradition of good road-holding which the P160 became noted for, although the team is still waiting for major engine modifications for their V12. A spare nose section of a slightly different shape was available as an alternative, while the shrouds over the side radiators were soon cut back to combat overheating in the official practice sessions.

Both Surtees TS16s appeared in their new Bang and Olufsen colours, Carlos Pace using TS16/02 and Jochen Mass was allocated a new chassis TS16/04, to replace the one which he spun into the pit wall during unofficial practice on the morning of the Race of Champions. Frank Williams brought along his usual entry for Arturo Merzario plus a second car for Tom Belso, the Danish driver, an arrangement made possible by his connections with Marlboro, while a singleton Embassy Lola entry was on hand for Graham Hill to drive and James Hunt handled the Hesketh 308 on its first outing in a World Championship race. The Hesketh team had their second chassis, 308/2, flown out to Johannesburg just in case any damage should be sustained in practice, but it stayed securely in its crate all weekend.

The local challenge was led by reigning South African Formula One Champion, Dave Charlton, an ex-works McLaren (M23/2) replacing his Lotus 72 in the colours of the Lucky Strike cigarette company. Their Lotus, 72/3, was entered for John McNicol, but was not ready in time to take part, though last year’s John Player Team Lotus 72s were out in force for Ian Scheckter (72/6) and Paddy Driver (72/7), both now running in the distinctive orange colours of Team Gunston. Keizan’s Tyrrell, 004, sported neatly constructed deformable structures round its monocoque, these having been made up locally.

Qualifying

Niki Lauda too his debut pole for Ferrari

Motorsport Images

Originally Kyalami’s leisurely schedule provided for practice on Wednesday and Thursday with a break on Friday before the Grand Prix took place on Saturday. Unfortunately, with marshals turning up late owing to a misunderstanding over times and the incomplete work on the catch fences at Barbecue Corner, the organisers decided in favour of delaying first practice until Thursday, a move heartily approved of by the majority of teams in view of the severe thunderstorm which doused the circuit during Wednesday afternoon.

When official practice started on Thursday it was clear that the strides forward made by Firestone over the winter months and emphasised by Hunt’s performance at Brands Hatch, would be maintained. But at Kyalami it was Pace in the Surtees TS16 who set the quickest time during the first session, injecting a good deal of confidence into the Edenbridge team even though one or two people doubted whether the Brazilian had recorded this quick lap. But 1 min. 16.63 sec. stood as fastest until the organisers reexamined their time sheets and discovered that Lauda had lapped the Ferrari in 1 min. 16.58 sec. The Ferrari team were almost hugging one another with this performance from the young Austrian for, although Lauda cannot he described as a “natural”, he is a willing worker who readily gives to the best of his ability. On the second day, when the temperature was even higher and, in consequence, lap times fractionally slower, Lauda again topped the list with 1 min. 16.66 sec. which meant that a Ferrari would be starting from pole position in a Grand Prix for the first time since Ickx at Nurburgring back in 1972.

Down in the Lotus pit, Ickx must have been reflecting on the wisdom of switching from the Italian team for Regazzoni was recording competitive times as well, the Swiss lapping in 1 min. 17.20 sec. on the Thursday and then slicing another 0.4 sec. off this time the following afternoon. The Lotus team were experiencing a fair degree of strife with their new cars and plenty of their rivals were outwardly trying to make a joke of their apparent chaos while inwardly realising that it will not be too long before Chapman sorts out his latest Grand Prix car and then they will have 10 start looking to their laurels.

Ickx was lucky on the first day, his car lapping quite reliably with little drama at just over the 1 min. 17 sec. barrier, but Peterson was spending most of his time hopping from his new car to his old one as all sorts of little things went wrong. Firstly the starter motor jammed and, as the automatic clutch system relies on the starter revolving in the opposite direction to normal in order to activate the pump which pressurises its fluid system, Peterson climbed. into 72/8 and recorded 1 min. 17.46 sec. before getting back into R9 towards the end of the afternoon. The next problem seemed to be an oil leak from the engine’s rear casting where the top forward parallel link is attached, so another lengthy spell in the pits was needed whilst mechanics checked whether it had cracked or not.

On Friday Ickx’s car developed a misfire owing to low fuel pressure while Peterson’s, by now running with its automatic clutch disconnected, firstly proved reluctant to fire up in the pit road and then developed a misfire of its own, particularly frustrating in view of the fact that it had rounded off Thursday’s session by losing its oil pressure and being abandoned by the Swede out on the circuit. Neither Lotus got below 1 min. 18 sec. on the second day, so their prospects for the race looked distinctly unpromising.

One quite outstanding effort came from Merzario on the second day, the little Italian hurling his Williams Special round in 1 min. 16.79 sec. to secure third place on the grid for Frank Williams. Frank was beaming from car to car after Merzario’s plucky performance which certainly earned him a capital “A for effort”, qualifying tyres or not, low fuel load or not. Belso, in contrast, had an unhappy time with an electrical problem stranding him out on the circuit on Thursday as well as gearbox trouble. He qualified last on the grid, so that the Williams sponsors, ISO and Marlboro, were at both ends of the scale of satisfaction.

Predictably Reutemann and Fittipaldi produced competitive times for the grid, but the Brazilian was not very happy with his McLaren’s handling at all on the first day, while Jody Scheckter had to use plenty of opposite lock with Tyrrell 006/2 to qualify for the outside of the fourth row. Another worthy surprise was provided by young Stuck, in the works March, who seemed to have terrific car control and still drives a Grand Prix car as though he were in a touring car. His efforts were worthwhile, for he pipped Schcckter junior for seventh place on the grid by one-hundredth of a second. Vittorio Brambilla was carefully keeping out of everybody’s way and, although he damaged a nose cone on Thursday, was not last on the grid for his first Formula One race by any means.

Ickx’ best lap earned him a fifth row start alongside Hulme’s McLaren M23, the New Zealander failing to reproduce the form which won him pole position in 1973. Most of the cars were the best part of a second slower than in 1973, slightly increased weight due to the deformable structure rules, bigger rear tyres and larger rear wings all being factors which could contribute to slightly lower speeds. Hunt’s Hesketh was far too slow down the straight for the peace of mind of designer Posthlewaite, so some adjustments were made to the rear wing which enabled him to manage 1 min. 17.61 sec. on the second day. The team also encountered what was thought to be fuel injection trouble, so they changed the engine only to find that fuel vaporisation had been the root cause.

John Watson managed a respectable time in the old Brabham BT42, while Peterson was sitting hack on the eighth row in his new Lotus reflecting that he could have been on the sixth row in his older 72, but as that wasn’t a worthwhile improvement this was clearly the time to concentrate on getting the new car right even if this was at the expense of immediate results. Depailler and Mass were looking rather glum, the latter unable to lap quicker than Hill’s Embassy Lola which is now creeping its way forward on the grids once more, its driver having gone from back to front to back and now part way to front again on starting grids during his 16-year Grand Prix driving career.

Neither of the BRM 160s were even remotely impressive, while most of the locals were suffering from a six-month lay-off with no practice for their racing cars at all in addition to having their first try in new machinery and endeavouring to match the seasoned Grand Prix competitors all at the same time.

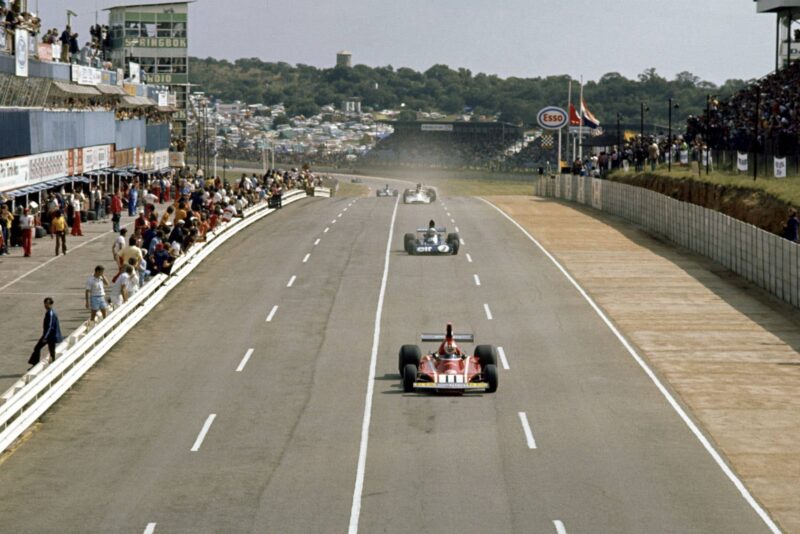

Race

The cars head for the first corner at the start

Motorsport Images

Although the ban on motor racing in South Africa has been lifted, there is still a ban on the sale of petrol between Friday evening and Monday morning and this factor, combined with the fact that South Africa does not yet have television, attracted a large number of spectators, many of whom stayed through the night camping just like the Europeans do at Nurburgring for example. There was plenty of enthusiasm and atmosphere with eager racing fans bursting with anticipation to watch their first motor race since the end of 1973. They came by car, by motorcycle, by public transport and even by helicopter. When the eventual takings Were added up, Blignaut announced that some 92,000 spectators had paid to come in and watch the South African Grand Prix, a terrific endorsement for the popularity of Formula One racing and an adequate comment against having too much motor racing generally.

Prior to the start there was a complicated “warming up” procedure which involved the field doing a pace lap on their own without an official car in front of them. The organisers put everyone on their best behaviour and emphasised that if anyone got out of line on this lap, they were not to be “naughty boys” and try and push back to their original position again. Needless to say, 27 Grand Prix drivers, all anxious to be getting on with their business, are interested in starting the race and not unduly worried over their correct positions on the pace lap. But they all arrived back at the startline in order and everyone was ready when the flag dropped.

Lauda and Fittipaldi were anxiously gesticulating to the starter to “get on with it” as their engines were starting to overheat on the line, and it was Reutemann who made the best start from the outside of the second row. He had to dodge round Pace, though, and Lauda beat him down to Crowthorne Corner by less than a length, Ferrari leading Brabham with Regazzoni and Scheckter squeezing in behind.

Further back there was some rather unruly “pushing and shoving” and suddenly Peterson found his throttle stuck open and the only person he could lean against was Ickx, so both the Lotus cars found themselves in amongst the catch fences on the first corner, whilst Mass got shoved by Pescarolo’s BRM and deranged his TS16’s nose section in the process. Pace’s Surtees almost spun in the middle of the corner, delaying both himself and Denny Hultne’s McLaren. All four delayed cars eventually managed to get going again, creeping round to the pits for attention long after the field went through.

Ferrari hearts leapt at the end of the opening lap for Lauda and Regazzoni occupied first and third places, their formation being split by that purposeful white Brabham. Fourth was Jody Scheckter, ahead of Hunt, Fittipaldi, Hailwood, Merzario, Depailler, Pace, Watson, Beltoise, Hill, Charlton, Stuck, Ian Scheckter, Watson, Keizan, Brambilla, Robarts, Migault and Driver. Ickx and Peterson arrived late, the Belgian’s car minus its nose section, and both continued although Peterson did only a couple more laps before stopping for good with damaged steering as a result of the collision. Ickx kept going for 31 laps, making a couple more stops, before he finally called it a day.

For the first few laps Lauda’s Ferrari maintained its slight advantage, but Reutemann soon starred to inch his way closer. The Austrian was driving to his complete limit and had nothing left with which to counter the determined Argentinian. Reutemann closed right up on to the Ferrari’s tail as they came out of Leeukop Corner to complete their ninth lap, rushed up beside him as they slip-streamed past the pits and deftly outbraked his rival into Crowthorne. Once past, Reutemann instantly opened an advantage of just over one second, but Lauda saw to it that this didn’t get bigger and the pair of them gradually edged away from their pursuers.

Third place was still in the possession of Regazzoni’s Ferrari, the Swiss being well-placed to protect his team-mate from any challenge from the bunch behind. But the second Ferrari was itself already pulling away from Scheckter, the Tyrrell team leader coming under intense pressure from Hunt’s Hesketh, Fittipaldi and Hailwood. Merzario was dropping away from this group slightly while great progress was being made by Stuck after his very slow start, the ambitious young German passing Hill and Charlton with ease although the local McLaren driver was left for 38 laps to sort out a way of circumnavigating the English Lola.

Hunt looked as though he might displace Scheckter, for the Hesketh almost got alongside on one or two occasions, but Lap 13 was unlucky for the Englishman as a driveshaft broke and stranded Hunt out at Clubhouse Corner for the rest of the race. But no sooner had the Hesketh retired than Fittipaldi renewed his attack on the Tyrrell and Scheckter, suffering from serious rear wheel vibration, eventually had to let him through on Lap 21. Behind Merzario ran a lonely Pace, disappointed that adjustments made in the unofficial session during the morning had upset the handling of his Surtees and now well out of the running.

Clay Regazonni leads the midfield pack

Motorsport Images

John Watson dropped from the duel between Ian Scheckter and Brambilla when a front wheel bearing started to break up and he was obliged to stop at the pits to investigate the trouble, leaving the Italian to sort out the local Lotus and then set off in pursuit of the Hill-Charlton battle. When he caught them he dived past in one neat manoeuvre, leaving a frustrated Charlton still behind the Lola. Hailwood chased through ahead of Scheckter, leaving him to the attention of his team-mate, Depailler, while Hulme started to shape up for an attack on Merzario even though the vibration from his front wheels was so severe that the needles on his instruments were banging themselves against the stops.

With the leaders pulling easily away, attention now began to focus on the progress of Beltoise in the BRM P201. By Lap 40 the Frenchman had moved past Hulme’s McLaren and began wearing down the margin to the pair of Tyrrells just in front of him. It was particularly interesting to watch that Beltoise always stayed clear of the slipstream from the cars he was pursuing. On the main straight the BRM always stayed in the centre of the track, about one car’s width to the left of the path taken by the others. But the BRM’s performance certainly wasn’t being hampered by failing to be in a slipstream and, with 44 laps of the Grand Prix completed, Beltoise went past Depailler’s Tyrrell. Scheckter took another lap for the BRM to deal with and then it was Hailwood’s turn to watch anxiously in his mirrors.

All three McLarens were being troubled by serious wheel vibration, but Hailwood nonetheless found himself being held up by Fittipaldi and elbowed his way past on Lap 48. But Beltoise was by now well and truly wound up in his enthusiastic pursuit and, although the Yardley McLaren driver resisted as strongly as he could, Beltoise moved up to fourth place on Lap 63. On Lap 66, Ferrari’s strong challenge started to fade. Regazzoni, still running strongly in third place and looking all set to consolidate his lead in the World Championship for Drivers, noticed his oil pressure gauge flickering as he braked for Leeukop Corner just before the main straight. He accelerated out of the corner and the needle sank to the bottom of the dial, so the Swiss immediately switched off the engine and coasted into the pit lane to retire.

Hardly having surmounted this disappointment, the Ferrari pit became apprehensive as Reutemann’s lead over Lauda started to increase. But the Ferrari kept coming round, although its driver was now keeping an anxious eye on his oil pressure, slipping the gearbox into neutral and coasting through the corners. Lauda kept his Ferrari on the move and his big advantage over Beltoise still seemed safe. Coming tip the main Straight to start his 65th lap, Lauda shook his head vigorously as he passed his pit, the Ferrari now sounding very ragged indeed. The end of the race was near and, at the end of the following lap, Beltoise appeared in second place after Lauda stopped out on the circuit with a dead engine.

For Reutemann, all that remained was to drive carefully round the remaining four laps to score a popular first Grand Prix victory, the first for the Brabham morgue since Bernie Ecclestone took it over, the last being in Jack Brabham’s hands at the same circuit four years earlier. Beltoise’s second place provided a much-needed confidence booster for the BRM team, while Hailwood’s third place means he is the only driver so far this year to have scored points in every Championship event, a stark contrast to his bleak 1973. season. Depailler’s consistent performance earned fourth for Tyrrell, although the Frenchman never demonstrased much flair, while Stuck’s energetic fifth place earned him his first helping of Championship points. Merzario survived to sixth after Fittipaldi dropped away in the closing stages.

Reutemann celebrates on the podium

Motorsport Images

In tenth place, behind Scheckter and Hulme, came Brambilla while Pace finally finished a disappointing eleventh in a car which he subsequently branded as “undrivable”. Right at the back of the remaining runners was Charlton, who, after finally getting past Hill, ran his McLaren up the back of Robarts’ Brabham at Leeukop and spent five laps in the pits having the damage repaired.