A second chance to make history for Jaguar XKR GTs

Two half-forgotten Jaguar XKR GT2 and GT3 cars from the British marque’s recent past have been united for a historic racing return. Gary Watkins charts their dual stories

John Colley

Jaguar and endurance racing, the Le Mans 24 Hours in particular, go together like strawberries and cream. Or they used to. A return in either the booming Hypercar class or the new LMGT3 division of the World Endurance Championship isn’t likely any time soon for a marque committed to selling only all-electric models from 2025. But if you thought that it’s now 30 years since the factory was last represented in the international sports car arena with Tom Walkinshaw Racing’s XJ220C in 1993, you’d be wrong. There were actually two works-sanctioned projects this century, and now the cars that all too briefly flew the flag for Coventry have been united and are set to return to competition in the historic ranks.

Between Jaguar’s unsuccessful Formula 1 campaigns of 2000 to 2004 and its entry into Formula E in 2016/17, the British manufacturer went racing with its aluminium-chassis XKR sports car. An XKR GT3 developed by Richard Lloyd’s Apex Motorsport organisation for 2007 and one of Paul Gentilozzi’s XKR-S GT2s, the very car – chassis 002 – that gave the British marque its last, fleeting appearance at Le Mans in 2010, are now in the ownership of historic racing specialists and Jaguar aficionados the Pearson brothers, John and Gary. One or both XKRs should be back on the track in anger this year.

The last Jaguar to appear at the Le Mans 24 Hours was this works XKR-S GT2 in 2010. It lasted four laps

Getty Images

In 2007 Jaguar made a return to international racing with the Apex-developed XKR GT3 – here at the FIA GT3 European Championship race in Dubai

DPPI

Jaguar ended its absence from sports car racing at international level in 2007 after Lloyd got its backing – but not its money – to enter the FIA GT3 European Championship. A British motor sport mover and shaker who would tragically die in a plane crash when the programme was barely a year old, Lloyd told this author that despite being the wrong side of 60 he “still had one more project” in him.

He was aiming to add to an impressive CV as a team owner. His GTi Engineering/Richard Lloyd Racing squad had won races in Group C in the 1980s, claimed Audi Sport UK a British Touring Car Championship in the 1990s and as Apex was key to the Team Bentley set-up that conquered the great race in 2003.

Lloyd had been intrigued by the new GT3 category announced in late 2005 and quickly approached Jaguar about going racing with its supercharged XKR. He was equally rapidly rebuffed by a company still under Ford ownership, before schmoozing with Jaguar head of design Ian Callum at the 2006 British Grand Prix. “I’d hardly got the words out of my mouth when Ian said, ‘That’s exactly what we should be doing,’” recounted Lloyd. “It struck a chord with Ian and he went off to try to get people on side.”

Apex had been largely dormant after the Bentley programme came to an end in 2003 after the Le Mans victory with the Speed 8. So once Lloyd got the sign-off from Jaguar, he needed to put the band back together. He immediately called Dave Ward, his team manager during the Bentley period.

Braking issues clouded the XKR GT3’s 2008 season. An update

was needed

DPPI

“Richard rang me up with the promise of taking Jaguar back to Le Mans,” recalls Ward. Lloyd didn’t make any secret of his wider aspirations for the new link-up with Jag — he called GT3 “a first step” at the time — though for the moment he had a much more modest deal. He would be given the XKR parts he needed to produce the race cars. (The first car to be delivered to the Brackley workshops of Apex was a red XKR from the press fleet.) The onus was on Lloyd to sell cars and drives with his team to make the project financially viable.

“We were working till 10pm every night to get the car done. Time was very short”

“We got the first car at the end of 2006 and because Apex still didn’t have many mechanics, I got involved in stripping it,” says Ward. “It was a case of pulling the engine back a bit, sending it over to Custom Cages [adjacent to the Apex workshops] and putting an Xtrac gearbox at the back. It was me and Howden [Haynes, another Apex returnee] working to 10pm every night trying to get the thing done. We wanted to launch the car in January, so time was very short.”

The GT3 Jaguar showed promise in the GT3 European Championship at Silverstone in 2008 – fifth, its highest position

Olivier Gauthier

And so was money. “We were going hand to mouth,” explains Ward. “We really didn’t have any money at all. We wouldn’t have made the opening race unless Stuart Scott had bought the first car.”

Scott was a British GT Championship racer and a fan of Lloyd’s from his days winning British Saloon Car Championship races in a Chevrolet Camaro in the mid-1970s. “I first met him when I was about 10!” he says. Scott had been approached about joining the investors in the project who included national level racer Harry Handkammer and a future director of Silverstone Circuits. His contribution was to commit to buying a car, and then a second.

Olivier Gauthier

Olivier Gauthier

Apex and Jaguar were on the entry list with a pair of XKRs for the opening FIA GT3 race of 2007 at Silverstone in May. But the car was prevented from taking part because its FIA homologation had not been completed. The compressed development schedule had been hamstrung by engine problems. Ward remembers its struggles with engine builder, Mountune Racing, trying to overcome the high inlet temperatures resulting from supercharged induction. “It’s why people no longer race supercharged cars,” he says.

The Jag wouldn’t debut in the series until the end of the year after making a first competitive outing in the Britcar 24 Hours, also at Silverstone, in September.

Jaguar’s PR guru Stuart Dyble, Apex’s Richard Lloyd and the XKR… Game on!

Jean Michel Le Meur

“I’d bought the car and wanted to race it,” recalls Scott. “The plan was to use the race as a test and dip in and out, do some night runs and other stuff. I was a bit annoyed, but we ended up finishing the race. Prior to that the car hadn’t run for longer than 30 minutes.”

“We designed the car as wide as it could go and still fit in the truck”

A belated FIA GT3 debut would come at the season finale in Dubai in November following outings in British GTs and ADAC GT Masters. Apex continued development of its XKR through the winter: among other details there was revised suspension geometry by Nigel Stroud, an old friend of Lloyd’s and designer of the 1991 Le Mans-winning Mazda 787B. The revisions were due to be tested at Nogaro in February, and Lloyd, David Leslie, who was down to drive, and young data engineer Chris Allarton were travelling to the south of France in a private jet when it crashed shortly after take-off from Biggin Hill. All three were killed along with the two pilots.

The backers, led by Handkammer, were insistent that the project should continue. Less than a month after the tragedy the Apex XKR took the best international-level result of its short competition career. Stuart Hall and Phil Quaife came home fifth in the first of two races at the opening weekend of the FIA GT3 series at Silverstone. Yet the car never came close to matching that result over the remainder of the season.

Olivier Gauthier

Olivier Gauthier

“It was the combination of two locals who knew the circuit and the car working pretty well around Silverstone,” remembers Hall. “The Achilles heel of the Jag was the braking, so at a fast and flowing track it was pretty competitive. Then we’d get to somewhere like Oschersleben with lots of slow corners, and it was a nightmare. I remember it ran out of brakes inside 30 minutes at Monza.”

Addressing the braking issues was among the targets of a major update of the XKR undertaken at Jaguar’s behest for 2009. The original concept of equal size front and rear was abandoned, resulting in the more bulbous look of a car dubbed the XKR-S.

Now in the ownership of the Pearson brothers, could track success finally come for these ageing Jaguars on

the historic scene?

Olivier Gauthier

“We went for a wider track with bigger arches,” says John Christie, a veteran of Nissan Performance Technology’s successful IMSA programmes of the late 1980s and early ’90s who’d been brought in to run Apex. “The width was determined by the size of our truck; we designed it as wide as it could go and still fit in the truck.”

Two of the three cars were converted to the later specification and entered for the FIA GT3 opener at Silverstone. There would be only one more outing before Apex closed its doors. There was, says Christie, “no one willing to pay proper money to race the cars”.

There had been Jaguars already racing in North America by the time Apex hit the track with its XKR. Or perhaps that should be ‘Jaguars’. Paul Gentilozzi’s Rocketsports team started representing the brand in 2000 in the Trans-Am silhouette series, then undergoing a minor renaissance if still a long way from its late 1960s and early ’70s heyday. The Jags he ran from 2000 were tubeframe racers clad in lookalike XKR bodywork and initially powered by a pushrod Ford V8. Only in 2003 would a programme that had the support of Jaguar’s US division switch over to the marque’s own multi-valve engine.

The links forged in Trans-Am were instrumental, says Gentilozzi, in paving the way for something bigger and better. In the wake of the takeover of Jaguar by Tata Motors in 2008, Gentilozzi travelled to the UK to meet with senior PR and marketing executives and talk motor racing.

“I was told Jaguar couldn’t go racing yet, but was asked what else we could do – they were about to launch the XFR and wanted to promote it. I said, ‘We take it to the Bonneville Salt Flats and do 200mph.’ I plucked the idea out of the air and had no idea if it was possible, but I wanted to start the relationship.”

A pre-production XFR that was only lightly breathed upon hit 223mph on the salt in November 2008 in Gentilozzi’s hands, eclipsing the previous mark for a production Jag recorded by the XJ220. Four months later, Jaguar announced it would be returning to international sports car racing in the GT2 class of the American Le Mans Series. The intent from the start was for the car to race at Le Mans in 2010.

“We’d had the relationship with Jaguar in the US and, I believe, served them well by winning multiple championships in Trans-Am, but the Bonneville car was an important project for us as a team to gain the trust of the company in the UK,” he said. “It undoubtedly played a part in us going forward into the GT2.”

The plan, as announced, was for the Jaguar, also known as the XKR-S, to begin racing in the middle of the 2009 season. That had to be pushed back. Gentilozzi’s team, now running as JaguarRSR, had its first stab at a GT2 car rejected. Its interpretation of the rules, with particular regard to the rear suspension mounting, was too extreme, it was told.

An appearance at the Petit Le Mans enduro at Road Atlanta at the end of September turned into just that: a low-key reveal in front of the media and then on-track demonstration. Even that didn’t go to plan. When the media turned up at the prescribed time for the unveiling, they were told that the car had been delayed. The team’s truck had suffered a puncture on the way to the track. It might be regarded as some kind of omen given how the project panned out over the next two years.

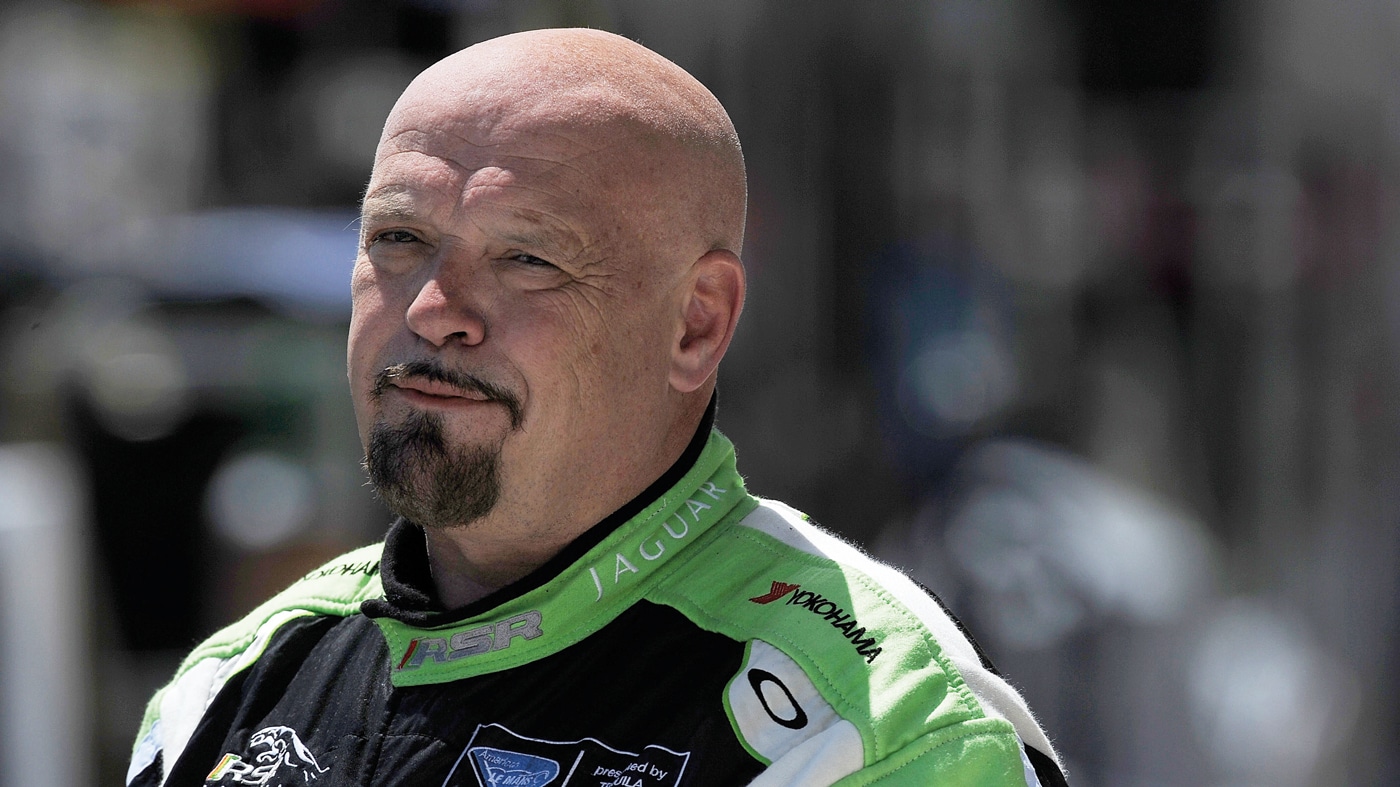

JaguarRSR driver and team owner Paul Gentilozzi personally added to the racing budget

Getty Images

The XKR-S, driven by Gentilozzi and new signing Marc Goossens, failed to set a qualifying time on its debut proper at Laguna Seca the following month and retired early. It didn’t distinguish itself in the three North American races with Goossens and Ryan Dalziel driving ahead of Le Mans in 2010, a year when there was no pre-event Test Day. It had been cancelled in 2009 as a result of the world financial crisis and wouldn’t return until 2011.

That was significant in what happened next. The ‘black box’ data monitoring device that race organiser the Automobile Club de l’Ouest insisted all cars run was incompatible with the Jaguar’s electronics. The Jag was beset by issues with its V8 engine through practice and qualifying and was slowest of all, ending up 13sec off the pace of the class pole winner.

What Dalziel calls “a Frankenstein engine” was created out of what was left after two days of problematic running. Just four laps into the race, the Jaguar took an early bath. Yet it could have been even earlier.

“I was struggling to keep up with the pack on the warm-up lap but they told me to keep going”

“I was struggling to keep up with the pack on the warm-up lap,” recounts Goossens. “I radioed in to tell the team that something was wrong, that I had no power, but they told me to keep going.”

“It was,” admits Gentilozzi, “a terribly unsuccessful Le Mans in total.”

The team’s struggles continued through the remainder of the ALMS season and then an outing at Zhuhai for the end-of-season Chinese round of the new Intercontinental GT Cup that led into the return of the World Endurance Championship in 2012.

Dalziel had gone into the programme with high hopes. “My dad was a Jaguar guy when I was growing up,” he explains. “On paper it looked good and it was going to get me to Le Mans for the first time, but it ended up as a year of a lot of head-shaking: it was both frustrating and disappointing.

The XKR-S GT2 was, according to Marc Goossens, outdated from the start

John Colley

“There were issues with both the reliability and the performance. Maybe if we’d had better reliability we would have been able to develop it into something more competitive. The big issue was the engine – and the gremlins we had never seemed to get fixed. I felt there was a tendency to blame the things we were bolting onto the car, like the Yokohama tyres we knew weren’t a match for the Michelins other people were running, rather than the car itself.”

Goossens believes that the XKR-S had “a lot of limitations”. He suggests it was old-tech in comparison with Chrysler’s SRT Viper GTS-R that he would race in the ALMS and at Le Mans just four year later.

“It was almost as if the car was out of date from the very beginning,” says the Belgian. “We were always struggling, and I don’t think we were ever moving in the right direction in terms of development. But I can’t say anything bad about Paul and his sons [John and Tony who respectively ran the team and built the engines]: there’s no doubt that they put the effort in to try to make it better.”

Goossen and Dalziel shipped out for pastures new at the end of 2010, to be replaced by a line-up that over the course of the following season included IndyCar veterans Bruno Junqueira and Cristiano da Matta. Gentilozzi insisted and still insists that the corner had been turned with the arrival of a revised car at the Mosport round – he points out that the car set fastest race lap in class on its debut. The results, however, didn’t come and the programme was axed before the team could prove the new car’s worth.

“In year three we would have had a season working with proper tools,” says Gentilozzi. “We were gaining some reliability at the end of 2011 and getting there on performance: the revised car was a significant step forward. Unfortunately the authors of our programme, people like Mike O’Driscoll [Jaguar’s managing director], were no longer with the company. It was easy for our detractors to kill us off.”

Gentilozzi has an explanation for the engine problems that blighted the XKR-S: “The production block was not suitable for racing. In the first year we broke just about every mechanical component in the driveline. We would rip the crankshafts out of the block. So for the second year, with the help of Jaguar engineering, we had our own, stronger blocks and heads cast.”

“I should have convinced Jaguar to skip some races and gone testing on our own”

The other problem concerned engine electronics. Gentilozzi describes issues with the direct injection system “as our biggest setback through the opening races in 2011 before we switched to a MoTeC ECU”. He agrees that he and his team might have been overly optimistic as it set out to take on Porsche, BMW and Chevrolet, long-time players in North American sports car racing, and Ferrari in the GT2 ranks. RSR was trying to take on the big guns on a fraction of its rivals’ budgets. Gentilozzi dismisses the suggestion that the team received $6m (£3.8m) a year from Jaguar HQ. “It was less than half that,” he says, adding that he topped up the budget. “I put in $2.5m the first year and $2m the second. I could have said I wouldn’t do it for the money they were offering, but Jaguar didn’t have any more money to spend. I completely underestimated the budgetary pain, which is why I spent my own money. It was my optimism that got us into that situation and I felt I had to do whatever it took to fix it.

“Our problem is that we were developing the fundamentals of the programme in the public eye. I should have convinced Jaguar to skip some races and gone testing on our own.”

The RSR Jag never came good and never went back to Le Mans. The Pearsons hope to put that right next year with an outing for the car at the Le Mans Classic. A run at the Silverstone Festival this August is the first target for the XKR-S GT2.

The starting point to the Pearsons owning two 21st century Jaguar racers was a Ferrari GT3 they had been racing. “We thought, let’s do something with a Jaguar, because that’s what we are known for,” says John. “We bought chassis two [the only race car to remain in the original specification] at the start of 2022 and then the Gentilozzi car came up for sale last year through Duncan Hamilton ROFGO.

“It’s an important car. It will probably remain the last Jaguar to race at Le Mans.”

Thanks to Motor Racing Legends for the use of Silverstone, John and Gary Pearson and Alex Brundle.

Jaguar XKR GT3

Builder: Apex Motorsport (UK)

Years: 2007-09

Engine: 4.2-litre supercharged

Gearbox: Six-speed transaxle (Xtrac)

Power: 475bhp

Weight: 1300kg approx

Jaguar XKR-S GT2

Builder: JaguarRSR (Rocketsports)

Years: 2009-11

Engine: 5-litre normally aspirated

Gearbox: Six-speed transaxle (Lola/Hewland)

Power: 550bhp

Weight: 1295kg