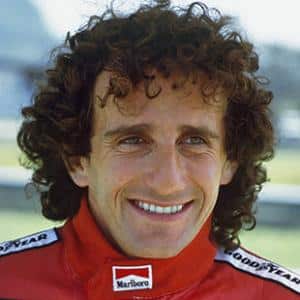

Alain Prost: 'It sounds like a joke but I’m completely underrated'

Alain Prost is one of the Formula 1 greats. But does he have a point about how he’s perceived today – especially in comparison to his sainted nemesis Ayrton Senna? In a rare interview, he reflects on a high-achieving racing life with Damien Smith

Jayson Fong

He divides opinion. Always has done. And it tends to distil to a single, fundamental question: are you for Senna, or are you for Prost?

Even Motor Sport can’t resist. We have been asking racing drivers that very question every month for our Life in Cars page, as if their answer identifies the deep-seated philosophy they live by. How they choose to express their art of motor racing. Pure, unadulterated, no-compromise speed borne from an instinctive passion; or a clinical, restrained sophistication emanating from a scientific approach to the business of winning? You don’t need us to tell you which camp Alain Prost represents. Lest we forget, he was the Professeur.

Ayrton Senna, Alain Prost, Nigel Mansell and Nelson Piquet, Estoril, 1986

DPPI

We’ve just tipped beyond 30 years since that final podium they shared in Adelaide 1993. A little under six months later Senna was gone, his blinding light extinguished against the Tamburello wall – his beatified legend only just beginning to shine. Prost, already in retirement, simply… survived. The McCartney to Senna’s Lennon. He toyed with a comeback, but fatefully chose instead to buy a team. Ligier became Prost Grand Prix and for five seasons made his existence a near-constant misery. He openly admits it was the biggest mistake of his life.

Today, at 68, the man remains something of an enigma, a figure from a fast-vanishing Formula 1 world who’s somehow fallen out of tune, caught in the everlasting after-burn of Senna’s white heat legend. Even Prost’s low-key presence as a guiding hand at Alpine turned sour, cast adrift in 2022 by CEO Laurent Rossi who would eventually too be shunted out of the F1 frame.

Alain Prost, Monaco, 1986 – a third consecutive win on the street circuit and a career favourite

DPPI

And yet. This is still the man who won those 51 grands prix and four world championships, who set the benchmark that Senna himself (and all the rest) strove to match through a full decade and beyond. This is Alain friggin’ Prost for Chrissake! A racing demi-god who belongs among the all-time greats – and who should be universally revered. Yet you sense he’s not. Why? Is there a tarnish that’s set in? If so, what’s caused it? And does he care?

As we discover, Alain Prost absolutely does care how he’s remembered. In fact, he’s angry and hurt by how too many choose to frame him. It’s time he reclaims his own story, beginning with his first one-on-one interview with Motor Sport for decades.

“I don’t speak very often,” says Prost as he takes a seat. “I’m very much still looking at motor racing and always with a passion, but I don’t find the right opportunity or desire to talk and talk and talk. Sometimes it’s OK, but not very often.”

On the eve of Motor Sport’s 100th anniversary year, it seems a fitting occasion to finally ‘get’ him. This interview has been a long time coming. But here, in the James Hunt room at the McLaren Technology Centre, he is in front of us. Master James looks down from the wall, irreverently sticking his tongue out. Prost, in cool blue suit and white pumps, looks at home in our sophisticated setting. The lines on his face, the unkempt hair, the doleful eyes, that fabulously crooked nose – yes, this is Alain Prost. He couldn’t be more French.

Prost stands at fifth in the list of Formula 1 grand prix winners, with 51 victories – above rival Senna

Jayson Fong

Richard Mille has brought him here. The luxury watchmaking brand is a McLaren partner, Prost is also a partner of the brand and special guests have gathered to meet him. Later there will be a Q&A with Martin Brundle and McLaren Racing CEO Zak Brown, plus dinner. But for the next 45 minutes (and more), Prost gives us his full and undivided attention. There’s no superstar ‘I am’ ego about him. He’s quietly spoken, shy in manner – normal. As we knew he would be. Yet at the same time he’s Alain Prost. Where on earth to begin?

Energy storage is his main preoccupation these days, he tells us, a business started during his stint as figurehead at Renault/Alpine. There is still a link to the automotive world because the business involves charging systems for electric cars, dealing in France and a smattering of European nations. He’s known Richard Mille for more than 30 years and it’s an easy friendship with a genuine (and influential) racing enthusiast. Mille is good company, as we discovered during a recent Motor Sport interview (Enthusiast with a racing calibre, December 2022), and has an enormous F1 car collection. Any Prost classics? “I know he has at least two, but he is very discreet about that. My first McLaren” – the M29 in which Alain made his F1 debut (and scored a point) in Argentina, 1980 – “and a Ferrari 643 [from 1991].”

Prost dominated his home French GP for Renault in 1983. But the title slipped away

Getty Images

Prost famously hit the ground at full speed when he first slid into a McLaren ahead of that first season. John Watson has spoken of how the French and European Formula 3 champion looked right at home before he’d barely left the pitlane in the shootout test that won him the drive. The point in Argentina was followed by two more in Brazil, before the reality of McLaren’s fall into mediocrity bit hard. A broken wrist brought him up short in a practice crash at Kyalami, and a move to Renault for 1981 looked tempting when his M30’s suspension broke in Montreal. He signed off with a concussion at Watkins Glen.

Ron Dennis and his partner in design, John Barnard, had just landed, but their arrival wasn’t enough to keep him from heading home to Mother France. “I even did Canada with John almost as my race engineer, and by then Ron had twice been to the factory,” Prost recalls. “Without the accident… I had a lot that year, but even though Watkins Glen was not their responsibility I had just lost the confidence, and said, ‘OK, I should go to Renault.’ But we kept good relations, and I always admired what Ron and John were doing. At the time also Marlboro was like a family – I was still a Marlboro driver. We kept in touch.”

Prost was reunited with his 1986 championship-winning MP4/2C at the McLaren Technology Centre in December 2023

Jayson Fong

Prost’s career can be butchered roughly into two halves: before the Senna rivalry properly kicked in, and after. The Senna years tend to dominate, but they really shouldn’t. The three seasons in Renault yellow and black, the return to McLaren, the string of wins that began to tot up, the will he/won’t he become France’s first champion… He was head and shoulders the most complete in that era, with all due respect to next-best Nelson Piquet (they had a high level of mutual respect), a returning Niki Lauda, mercurial friend Gilles Villeneuve, Alan Jones, René Arnoux, Keke Rosberg, Didier Pironi, Wattie – and many more. What a time it was as the first age of the turbos turned up the F1 boost.

“Most of the time I controlled what I was doing and pushed when I wanted to push”

So when did he peak? I’m thinking the long-awaited first championship years, 1985/86. Or perhaps 1989. Maybe the first season at Ferrari, 1990. He looks away and pauses for a full 10 seconds. “I take time to answer that because I was at my peak when I decided to be,” he says. “I always, or at least most of the time, controlled what I was doing and pushed when I needed to push – and when I wanted to push.” What a perfect Alain Prost answer! “I did a fantastic 1990 season, in my opinion. But even with Ayrton in 1988 and 1989, considering 1988 was different [to what he was used to] and ’89 was very difficult mentally… it’s difficult to say. I never found myself saying, ‘You are going down.’ I never felt that. When I stopped in 1993” – as a newly crowned four-time champion after his single year at Williams – “I was still as good as I could be. For a driver you need to be at your peak when you have all the elements come together. Psychology is a big, big part of performance. Some years were more difficult than I might deserve, in my opinion – for different reasons. I always considered I could have been much better.”

The Frenchman joined Ferrari in 1990 after a tumultuous final season at McLaren

Grand Prix Photo

The triumvirate of Renault seasons are a particular frustration. “Yes, in 1982 and 1983 without the mistakes we should have been world champion, for sure,” he states. “It’s a big regret because it was a French team. Even when Renault won with Williams, it was a French engine but an English team, and with Benetton [in 1995] it was also an English team too.

“In 1983 we had the problem with the fuel.” How Prost lost a 14-point lead after victory at the Österreichring with four races to go cannot be tied to a single factor. There was his uncharacteristic crash into Piquet at Zandvoort for starters, but what smarted then and now was the infamously potent brew that powered BMW to become the first turbo champion in the back of Piquet’s Brabham BT52 – and how Prost took the fall for the humiliating defeat, in a team that had initially been laughed at for pioneering forced induction in the first place. “It was easy to make a protest but we did not want to do it, so it was a political problem,” says Prost, whose time at Renault ended under a cloud. “It shows that for a big constructor in F1 you need to have all the parameters [covered]. And 1982 was a disaster because I stopped nine times, mostly for the same reason.” He’s referring to infuriating retirements caused by faulty fuel injection. “It was a small electrical motor that cost 20 dollars they did not want to change because it was a part used in the group. I always said an English team would never have done that. Nobody would have known. You have to be pragmatic in motor racing.”

As team-mates in 1988, Prost and Senna were almost unstoppable in the MP4/4, winning 15 of 16 GPs – with Senna pipping Prost to the title

Getty Images

By our count, Prost could have ended his career as at least an eight-time champion, the ones that got away being 1982, ’83, ’84 and ’88. We can’t forget 1990 either, when a Senna torpedo took him out at Suzuka’s Turn 1. Losing by F1’s closest margin, half a point in 1984, perhaps should have hurt more than it did. In fact he describes that time as a “dream”, thanks to his relationship with Lauda and for all he learnt against the ageing master. “I was never disappointed or depressed, even if half a point was difficult,” he says. “Two or three laps more at Monaco” – the infamous red-flagged race against Senna’s fast-closing Toleman – “and it would have counted as a full result, then even with Niki finishing second in Estoril I would have been world champion. The ambience was so good in the team, even if I was reading in the press all the comments that ‘Alain Prost will never be world champion’. I was unlucky with reliability but there were also one or two mistakes because I was fighting more against Nelson. We were always on the front row and Niki was a bit behind. I always considered my main target was Nelson and that was a mistake.

“In 1985 I approached it differently. I was much more disappointed that year when I won the race in Imola and was disqualified for being underweight by 600 grams, after the podium ceremony. At that point I did think maybe they are right, I’m not going to be champion.”

Prost met Senna just before this Nürburgring exhibition race in 1984 organised by Mercedes; their rivalry started here

Grand Prix Photo

But he accepts the old racing mantra ‘coulda, shoulda, woulda’. “It’s part of history, you always have something to say about such things. In 1988 I had more points than Ayrton, but the regulations…” That was when only the best 11 scores counted, so Senna won his first crown. “You can always have stories like this. But yes, I could have won more.”

“It was only in 1988 when I saw Ayrton in the same car that I knew how good he was”

He first met Senna properly when they drove from the airport to the Nürburgring together for the famous one-make Mercedes 190E race to open the new, shorter version of the circuit in May 1984 – just before Monaco. So when did Prost realise this Brazilian kid would become his most troublesome rival? “When I got the pole position and he jumped the start! I didn’t know how good he was, but we knew… I understood. It’s difficult to tell until you are in the same car. I saw him in many different situations. For example, in the Toleman at Monaco it was the first year with carbon brakes, it was very wet and the temperature was going down, so it was really undriveable at one stage. He still had steel brakes on the Toleman. Then I saw him in 1985 in Estoril when he won the race [for Lotus], but I was blocked by Elio [de Angelis]. I don’t know whether I was able to beat him, which would have meant overtaking him. But I couldn’t overtake Elio anyway. Even when he was getting pole positions with Lotus the Renault was the most powerful engine in qualifying. So it was only in 1988 when I saw him in the same car that I knew how good he was. Then at our first test together in Imola I saw it was going to be difficult.”

The infamous Turn 1 collision at the 1990 Japanese GP. Both were out of the race and Senna was world champion again

Grand Prix Photo

To his eternal credit, it was Prost who suggested and encouraged the signing of Senna. Dennis is said to have wanted Piquet. “And I don’t regret that,” says Prost. “I don’t regret many things. It was my family, my team. You know, with Ron when we had a new sponsor, we went to meet them together. When we went first time for the Honda engine almost two years before we got it [in ’88], we went together. It’s not very often you bring a driver to such a meeting. It’s almost like you are a shareholder. Mansour [Ojjeh, a real McLaren shareholder and founder of TAG] was also a very good friend. This situation was not under control any more and it was a shame.”

We’ve fallen into the obvious subject already. It’s inevitable. Does it frustrate him that his career tends to be viewed most commonly through the prism of his rivalry with Senna? “It looks like it stays that way for ever, it is part of the history,” he shrugs. “Sometimes you don’t understand why it is so much, but it is also unbelievable so you have to be positive. Look at my other team-mates: Watson, Arnoux, [Eddie] Cheever, Niki, Keke, Stefan [Johansson], Nigel, Jean [Alesi] and Damon [Hill]. Nobody talks about them. I had five world champions as team-mates, so it is a bit of a shame. But it is the way it is. Today you have social media and everybody is coming back to videos of our fights. Sometimes I don’t understand. For me it’s a shame too, because what is more important for me is talking about family, the work we have done. Even when I was at Ferrari the first year was fantastic, the human story. My career was not only two or three years.”

Those incendiary seasons, 1988-90 – the first two as increasingly toxic team-mates at McLaren, the last as rivals in different camps – cannot be something Prost looks back on fondly. “I cannot say I enjoyed it the same, I cannot lie. Before I enjoyed racing, enjoyed fighting. Remember with Nelson, we were going on holidays together the same year we were fighting for the championship in 1983.” Prost raced mostly against good friends back then – a different time. “Keke was unbelievable, one of my best team-mates. Everybody said at the beginning of the year it would be a disaster. Then when Ayrton came we reached a level of performance and obviously you enjoy it a little bit less. When I was fighting with Keke or Niki or whoever you had fans. But with Ayrton the fans were… even if it was 50-50, they love you – or they hate you. The difference was huge. I tell you, I really suffered a lot, so you cannot enjoy it the same way. And one of the countries where I suffered the most was France. It’s always in your own country. I cannot say I enjoyed the fight – and I lost some performance because of that. I’m the kind of person who needs to be free, needs to be happy. I need to have fun and relax. It was more difficult.”

In 1988, rules dictated that only the 11 best results would be counted in the championship. Prost’s points tally was 11 more than Senna before deductions, but Senna scored more wins and the title was his

Getty Images

“Ayrton represented more panache. I was the ‘Professor’. He was ‘mystic’ – people liked that”

We’re shifting into the uncomfortable territory of how he is remembered, so I push him a little. Why does he think he’s less popular than Senna? “Ayrton represented more panache. I was the ‘Professor’, clinical. He was ‘mystic’ and people liked that.”

Prost has been forever labelled ‘political’, as if he was some Machiavellian mixer, cannily shifting the pieces behind the scenes for his own benefit, and to the clear detriment of his team-mates. Speak to those who worked with him and all they talk about is his high work ethic, how great he was within a team environment. It’s a perception that clearly irks him – and he largely appears to blame Mansell, one of the most political drivers of them all.

At Monaco in 1986 Prost was a class apart, only losing the lead for a few laps to take on fresh tyres

Grand Prix Photo

“It is really frustrating, a shame,” he says of his reputation. “I don’t know why. If you look at the Senna film” – not the last time he mentions the documentary that caused him so much pain – “you have [FIA president Jean-Marie] Balestre in the middle of everything, and he was French. This story in Japan [over which side of the track pole position should be on in 1990] is ridiculous. It was Ayrton’s decision the year before [to start on the right]. People never tell the [full] story, even some media. There are two things. This story and Nigel very often saying I was political. You know why? Because I was speaking Italian at Ferrari. We never spoke Italian in the briefing, it was always in English. So I never understood. There is a sort of frustration. I was trying to do the best job, like everybody, trying to get the best things that are good for me. I never asked anybody to set up my car, that is for sure. I never hid anything about my car – and the other drivers couldn’t drive my set-up anyway. I always did my job. Political? I don’t accept that.”

Reading those words back, he sounds animated, doesn’t he? But in delivery Prost is always calm, softly spoken. Yes, he’s clearly angry – but mostly he seems bewildered. Hurt. So, what people think of you, it does matter? “I do ask myself sometimes how I am going to be remembered. What you said about the political things… It sounds like a joke but I’m completely underrated! I know that. I can see. I don’t know why, but it’s my brand in a way.”

He then offers a fascinating insight into what mattered most to him as a racing driver, what it was all about for him in a nutshell – and it had nothing to do with any rivalry. I ask him whether he was aware how good he was. “I think so, but all F1 drivers will tell you the same. You need to have that. What I miss the most in my life is working in a team, especially when we had smaller teams, working with the engineers. Ron was there too, and John. Or Adrian [Newey at Williams]. Always thinking, talking, trying to improve things. You are always in this way. I started to think and set up the car like this, like this, like this, to the point where – shit… That was what I liked the most. I did 199 races and there were maybe three or four where I touched perfection. But perfection for me is not about myself. It’s the combination of the work, the set-up and what I do with the car.”

Piquet, Prost and Mansell – the three drivers in contention for the 1986 world title at Adelaide

DPPI

Can he recall which races? He names three. “For sure, Monaco 1986.” On pole by a gaping 0.4sec over Mansell’s Williams, then a faultless race drive in which he finished 25sec ahead of team-mate Rosberg. Senna was third in his Lotus – 53sec down on the winning McLaren. Pure Prost – but for the paying public, not particularly memorable. Which is typical.

Next? “Adelaide 1986.” One of the most dramatic grands prix ever, involving Goodyear tyre worries, Mansell’s infamous blow-out, a cautionary stop for Piquet – and Prost’s stealth to capture the title he cherishes the most of his four. A puncture had forced him to stop, but a negative fuel read-out in the closing stages left him uncertain to make the finish. How he did so, just, is the stuff of Prost legend. The image of him emerging from his dry McLaren after taking the flag, raising both arms in victory, is one of his signatures.

And the third race? “1990, Mexico.” Mansell’s outside pass on Gerhard Berger at Peraltada tends to hog the limelight. That’s also typical for Prost, because it overshadows perhaps his most un-Prost-like drive involving bare-knuckled hand-to-hand combat. Unhappy with his qualifying set-up on the Ferrari 641, he focused on the race and lined up just 13th – his worst grid slot since his rookie season. How he came through to win, passing Senna and Mansell along the way and beating his team-mate by a full 25sec over the bumps, gives him great pleasure, still. “It started from the Friday,” he says. “I told my team after qualifying 13th, ‘I am going to win this race.’ I don’t know what I bet, but I said, ‘I am going to win – easy. If I don’t crash on the first lap.’ I knew.”

Another of Prost’s special races – the 1990 Mexican GP

Getty Images

The recent Renault/Alpine spell has given him insight into the workings of modern F1 teams. Can drivers still make that crucial difference just as he did? “Yes and no. You can feel it, for example, with Max [Verstappen] because it looks like there is more control, but only with him. I was still there in F1 two years ago, I can see the way they work and it’s completely different. When I was racing I had the perfect overall vision of everything, and today that is impossible. When you have a briefing with 35 people you cannot have the same feeling. When briefing with Ayrton and Niki there were five around the table. But briefing was one thing. Then you were continuing all day and into the evening, thinking, modifying. I was modifying the set-up on the grid, out of 199 races a minimum 100 times. Minimum. That was, for me, pure racing.”

Graft. That’s what Prost was all about. No out-of-body experiences. In his way, he speaks just as evangelically about racing as Senna ever did. But set-up talk rarely stirs the soul.

We return to the old subject. Their final season together – and what turned out to be Senna’s final full season too – left a sour taste for Prost, despite that fourth title in the wondrous FW15C. He couldn’t enjoy that final year as an F1 driver.

“Frank was Frank, I can understand his position,” he says. “Patrick [Head] was really straightforward and he did not want me to leave, even when I said to him that I had had enough. I could have stayed. I was not ready to stop. But you don’t enjoy it: when you win it is because you have the best car, if you lose… Even inside the team it was not very nice.”

The spectre of Senna hung over the season. Prost says he knew he would be coming for 1994, even when he did his own deal for ’93, and the thought of pairing up with Senna again was intolerable. Not because he was running scared. That’s too glib. “When he impressed me I must say it was in qualifying sometimes, I don’t remember when exactly. Never in race conditions. Never. In race conditions, in the warm-up, most of the time I was quicker.”

Prost GP’s Jean Alesi and the boss, Silverstone, 2000

Getty Images

But Senna’s imminent arrival did trigger his own retirement, even if it wasn’t about fears over getting beaten. Why on earth would he have wanted to put himself through that stress? Last time it had been utterly exhausting. Just imagine doing it again.

“You know how it was. When Ayrton wanted to have something… and Renault wanted him. Ayrton was calling them, calling Patrick [Faure, Renault Sport’s president] all the time. He even called one evening when I was with Patrick. He said to him, ‘You want to have a reason why you should take me? Because God is behind me.’ Patrick Faure was really impressed by that.”

“I hadn’t realised how much Ayrton had focused on me”

There are a multitude of reasons why this rivalry remains the most celebrated – and the most dire. It was primarily from Senna’s obsession with Prost. Even before he made it to F1, Ayrton had zeroed in on Alain as the man not only to beat, but to obliterate. “He told me,” says Prost. “Many times after when we talked about it. I hadn’t realised how much he had focused on me before he made it to F1. His motivation was to be world champion, but his biggest motivation was to beat me.

With Williams in 1993 for his fourth title

“There were three Ayrtons for me: the one before F1 when he was looking at my races, at everything I was doing, the way I was doing it; obviously the one when we were together, inside or outside the same team; and then the one when I retired.” It was this last version that Prost says he grew to like adding he wouldn’t have believed it existed “if I had not known this person myself”.

In that short time between Adelaide 1993 and Imola 1994, Prost saw an entirely different side to his old nemesis. “We were talking very often, every week, twice a week. I knew everything about the Williams, everything about his position in the car, everything about what he was asking, everything about the fact he was not happy in the team, everything about his personal life. Amazing.”

Prost with Alan Permane. Both have left Alpine

Alamy Stock Photo

Later, in the Brundle/Brown Q&A, he explains why it couldn’t be that way when they were competing against each other. “Once we were in Geneva for Honda at the motor show and I invited him to have lunch at my house, about 20 minutes away. He came with me, we went into town, we had lunch. After the lunch he wanted a nap, then coming back to the motor show he did not want to talk to me at all. I told this to a Honda guy and he said, ‘You don’t need to tell me the story, he did not want to talk to you. He did it on purpose because he did not want to be friends, he does not want to have a close relationship.’ That’s what impressed me in a way about him. He had a way of trying to beat me, and he did not change until the podium in Adelaide.”

So, Prost or Senna? Like the old Beatles vs Stones question, no one ever seems to answer “both”. But surely the world was better that these unique entities just happened to co-exist, that we could witness them sharing the same time and space. It’s also why the version of the tale put up in Senna still rankles, because the truth, as usual, is so much more interesting.

And finally, Prost is ready to tell his side. He’s finishing his own (French) documentary and has plans to write a book. In the Richard Mille Q&A later on he reveals he hasn’t kept any of his cars or many of his trophies. But the past still matters to Alain Prost. He is energised by his present and his future – but in the age of social media and YouTube, this quiet legend will never be allowed to move on from his past. Then again, given what he achieved and how he went about it, he really shouldn’t have to.