Long Beach 1976, the greatest historic race ever staged

California, 1976: how do you convince US motor sport fans brought up on oval racing to pay to see Formula 1 in their own backyard? As Preston Lerner reveals, the answer was to host the most incredible support race the world had ever seen – a historic blow-out with a cast of star drivers and machines

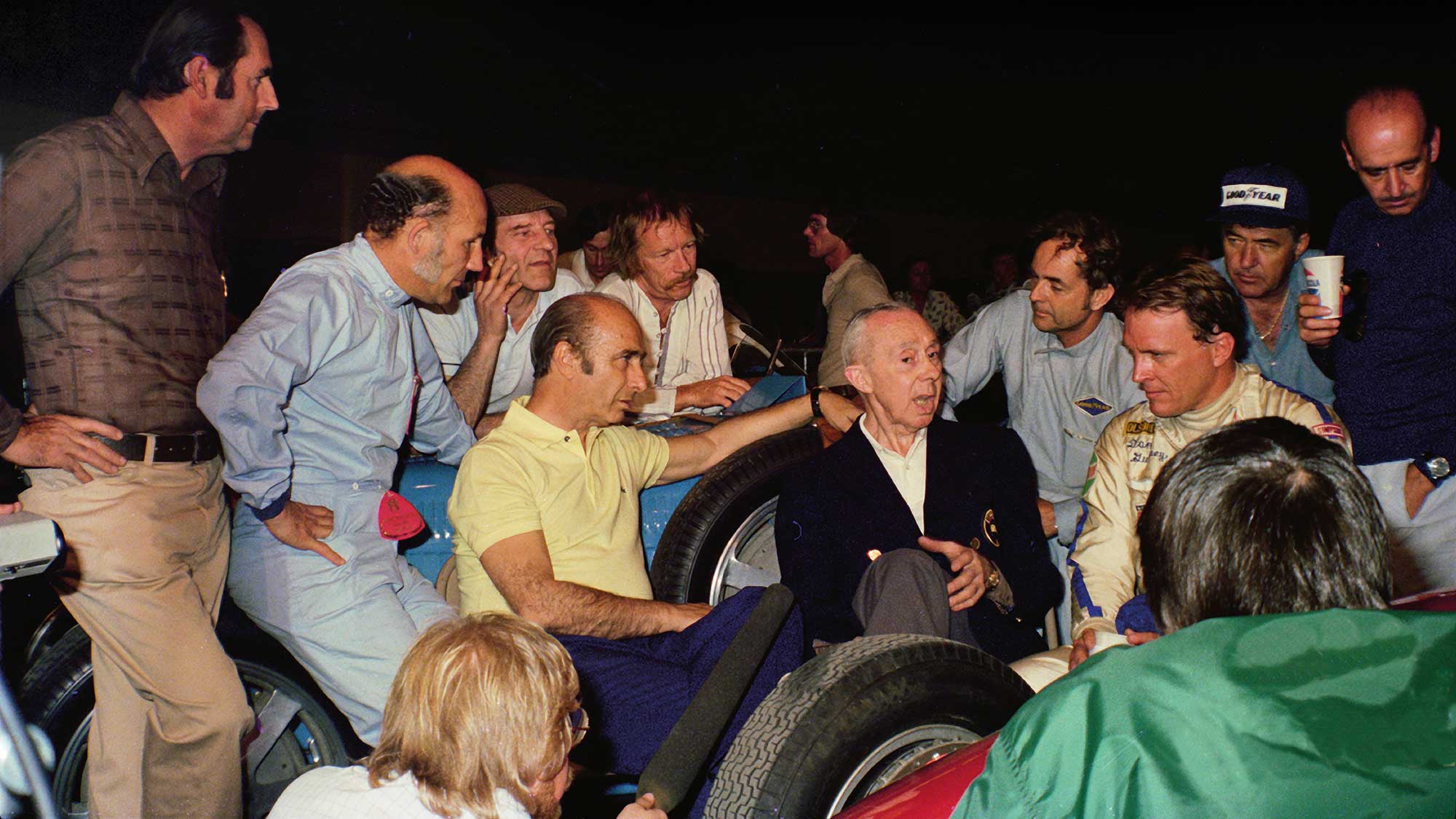

Some of the finest F1 names flocked to California in 1976. From left: Jack Brabham, Stirling Moss, Innes Ireland, Juan Manuel Fangio, Richie Ginther, René Dreyfus, Phil Hill, Dan Gurney, Carroll Shelby and Maurice Trintignant.

Phil Reilly Collection, Larry Crane

Most halfway serious race fans know that the inaugural Long Beach Grand Prix – technically the US Grand Prix West – ushered in the age of modern street circuits in 1976. But only the geekiest trivia hounds know that the event also featured perhaps the greatest historic race of all time.

Imagine an entry list with 12 drivers who’d won 10 world drivers’ championships, 10 Monaco Grands Prix, six Le Mans 24 Hours and 73 points-paying Formula 1 races, not to mention 64 non-championship F1 events and one Indianapolis 500 thrown in for good measure. As Jim Stranberg, who worked at Long Beach as a Bugatti mechanic, puts it, “At that race, I met every hero I ever had – at least the ones who were still alive.”

These days, of course, the legends of yesteryear turn out en masse year after year at lavishly funded and meticulously curated celebrations of motor sport history such as the Goodwood Revival and the Porsche Rennsport Reunion. But in 1976, historic racing was in its infancy, especially in the United States, and gatherings of this sort were still the stuff of fantasy.

Striling Moss in hi 1954 Maserati 250F.jpg

Phil Reilly Collection, Larry Crane

Maurice Trintingnant took the wheel of Briggs Cunningham’s 1952 Talbot-Lago.

Phil Reilly Collection, Larry Crane

The Bugatti’s steering was too heavy for Dreyfus; Phil Hill stepped in.

Phil Reilly Collection, Larry Crane

from left, Garlands for Moss, Fangio, Trintingnant and Gurney

Phil Reilly Collection, Larry Crane

Steve Earle had staged the first Monterey Historic Automobile Races at Laguna Seca Raceway only two years earlier. While getting the event off the ground, he met a would-be motor sport entrepreneur named Chris Pook. British by birth and a tour agent by trade, Pook had a dream – some sceptics called it a delusion – that holding a Formula 1 race on the streets of downtown Long Beach would help transform a seedy port city filled with dive bars and X-rated movie theatres into an internationally renowned destination metropolis.

Against all the odds, Pook lined up support from civic leaders, and the first Long Beach Grand Prix was held in 1975 for Formula 5000 cars as a proof of concept. Brian Redman beat a stellar field including Mario Andretti, Al Unser, Jody Scheckter, Tom Pryce, Tony Brise, Jackie Oliver and Chris Amon. The race was so successful that the FIA gave Pook a date for an F1 GP six months after the temporary grandstands had been disassembled.

“The Formula 5000 race was so successful that the FIA gave a date for an F1 GP”

A born promoter, Pook realised that an F1 race alone might not be enough to attract Americans who were more accustomed to oval-track racing. “We needed to educate the fans,” he says. “All they knew were stock cars and Indycars at Ontario [Motor Speedway] and Riverside [International Raceway]. We wanted to get the public and the media in our market – which we defined as the 11 western United States – familiar with Formula 1 and its lineage.”

Steve Earle was the obvious choice to spearhead the support project. By happy coincidence, the two co-directors of the F1 race were Dan Gurney and Phil Hill, and they eagerly agreed not only to compete in the historic event but also to help entice other participants to travel to Long Beach. Meanwhile, Earle drew upon his contacts in what was then a tiny community of American race car collectors to provide most of the machinery.

Mercedes pulled out all the stops to ensure that Fangio could race a W196 at the California circuit

Getty Images

Hill was initially entrusted with a 1932 Alfa Romeo 8C 2300 Monza from a private collection.

Phil Reilly Collection, Larry Crane

Dreyfus was 70 when he arrived at Long Beach. Linda Vaughn was a pit regular in the US, a mix of model and sassy marketeer

Getty Images

Former Mercedes team-mates Moss and Fangio with a W196

Getty Images

Joel Finn, who would later write several exhaustive histories of road racing, brought no fewer than three cars – a 1957 Maserati 250F for Innes Ireland, a 1932 Bugatti Type 51 for René Dreyfus and a 1957 Formula 2 Cooper for Denny Hulme, who’d helped design the Long Beach circuit. Bob Sutherland, the passionate scion of a timber fortune, entered two more cars – a 1927 Bugatti Type 37A for Richie Ginther and Stirling Moss’s old 1954 Maserati 250F, to be driven by the British racing hero himself.

There were also four singletons. Briggs Cunningham, the grand old man of American road racing, pulled out a 1952 Talbot-Lago T26C from his extensive collection for Maurice Trintingnant. Ernie Beutler showed up with the 1952 Ferrari 375 that had been driven in the Indy 500 in 1952 by Alberto Ascari. It would be raced at Long Beach by Carroll Shelby. The 1932 Alfa Romeo 8C 2300 Monza owned by Roberts Harrison, from a well-heeled Philadelphia family, was entrusted to Phil Hill. The entry list was filled out by the oldest car and driver in the field, Pete DePaolo, 76, who’d won the Indy 500 in 1925, and a 1926 Bugatti Type 37 owned by Bill Serri Jr, a collector who’d bought his first Bugatti while he was still in high school.

“It is too bad it is impossible to turn the clock back and have a real race”

Inevitably, there were a few no-shows. The blue and white Ferrari 158 F1 car that John Surtees had raced at Watkins Glen and Mexico in 1964 didn’t arrive. Neither did the V6 Ferrari 246 that Phil Hill had driven during the 1960 grand prix season. Gurney had intended to run the Eagle that carried him to victory at Spa-Francorchamps in 1967, “But we were busy with our Formula 5000 and USAC projects,” he said. “There wasn’t time to get it race-ready.”

Jack Brabham racing in the Tom Wheatcroft-owned Cooper T51.

Phil Reilly Collection, Larry Crane

Moss with Ireland – the latter was in typically effervescent mood

Phil Reilly Collection, Larry Crane

The prospect of holding the historic race without Gurney was unthinkable. Earle called top British racing car collector Tom Wheatcroft, who generously agreed to send over a pair of 1959-vintage F1 cars – a BRM P25 for Gurney and a Cooper T51 for Jack Brabham. But Pook and Earle wanted an even bigger attraction. So Earle phoned Leo Levine, Mercedes-Benz’s American PR director, to request both Juan Manuel Fangio and a W196 open-wheel car.

Levine, a journalist who’d written the magisterial history Ford: The Dust and the Glory, before transitioning into public relations, was notoriously unwilling to suffer fools gladly. “What are you, nuts?” he snapped at Earle. “You think we’re going to send a car that’s worth more than anybody can imagine – and get Fangio too?”

“I’m sure there has never been as many racing stars gathered together”

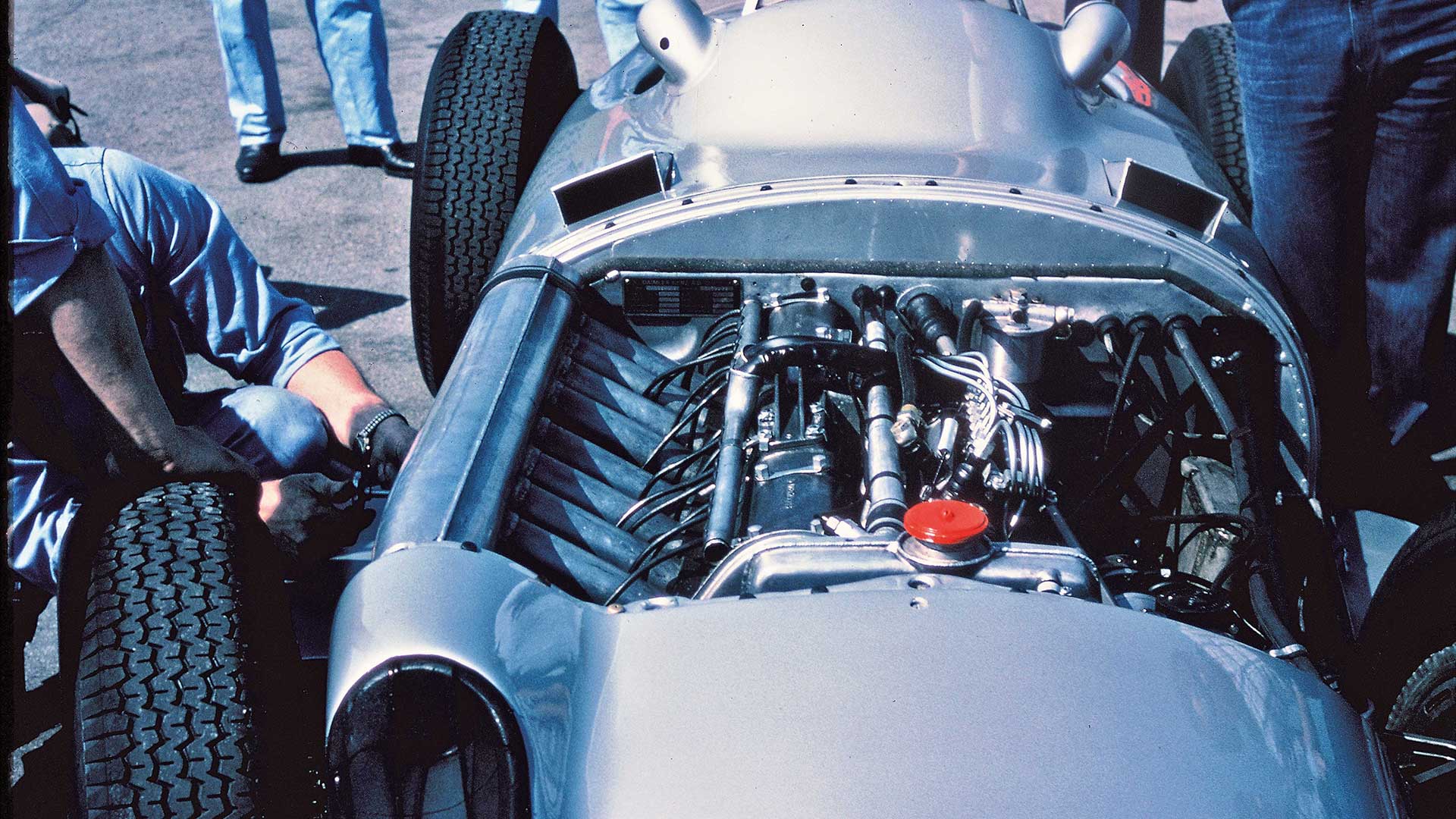

But that’s exactly what Mercedes did. To generate publicity, Levine rented Ontario Motor Speedway for a pre-race shakedown. Media types streamed out to interview the famously gracious Fangio and watch the W196 on track. Although Mercedes dispatched five factory mechanics from Germany to support the car, the local gasoline didn’t agree with the desmodromic straight-8 engine under the long, silver hood.

British car collector Wheatcroft also sent a 1959 BRM P25 for Dan Gurney to race

Phil Reilly Collection, Larry Crane

“The motor dropped dead,” Earle recalls. “It was a total panic situation. They’re on the phone to Germany, where, of course, it’s the middle of the night.”

The powers that be decided to send the original streamliner version of the W196 to Long Beach. Then somebody pointed out that an envelope body was exactly what you didn’t want on a street circuit. So Mercedes reacted as only Mercedes could: the company pulled out a third W196, this one with open-wheel bodywork, prepped it ASAP and flew it to Long Beach.

While the Mercedes drama was unfolding, another pre-race media event was held to promote the forth-coming historic race. “I’m sure there have never been as many international racing stars gathered together at one time,” Pook declared. “That event alone would be worth the price of admission on Saturday.”

The festivities gave Ireland, the perennial bad boy, an excuse to perform a series of showy wheel-spinning launches in Finn’s 250F – until he roasted the clutch. “Joel was not a happy camper,” Earle says. So the Maserati was an early scratch. Then DePaolo contracted flu and withdrew from the race.

Friday practice was, well, interesting. Dreyfus could barely operate the heavy steering of the Bugatti Type 51, so he swapped cars with Ginther, who’d been in the lighter Type 37A. Shelby wasn’t happy with the handling of his ponderous Ferrari, which he described as “a big old tub”. Moss was having trouble with the engine of his 250F despite the help of his personal mechanic Alf Francis. Meanwhile, Hill had more serious issues with his Monza.

Mercedes prepped this W196 against the clock and flew it to the US from Germany.

Phil Reilly Collection, Larry Crane

Hill battled “carburettor problems” with the Monza

Getty Images

Ireland leapt into Dreyfus’s Bugatti

Phil Reilly Collection, Larry Crane

“Phil characterised it as a carburettor failure,” Phil Reilly recalls. “The carburettor was broken off the side of the motor by a connecting rod.” Ouch!

Reilly, who went on to run one of the best-known restoration shops in the country, was working at the time as a mechanic on the Alfa Romeo prepared by his boss Stephen Griswold. With the car rendered hors de combat, Reilly spent the rest of the weekend using the credential Earle had given him to roam the track and take most of the photos seen here. Hill, meanwhile, took over the Bugatti that was supposed to have been driven by DePaolo.

“It was a sun-kissed morning and the grid looked magical”

After practice, the drivers convened in the Long Beach Convention Center for a TV interview. Larry Crane, who went on to have a long career as an art director of books and magazines, happened to swing by, and he took the marvellous group photo that later hung in a place of honour in Le Chanteclair, the French restaurant that Dreyfus and his brother ran in midtown Manhattan.

Fangio rolled back the years in the Mercedes, posting a fastest lap

Phil Reilly Collection, Larry Crane

Moss also faced engine issues with his old Maserati.

Phil Reilly Collection, Larry Crane

Wheatcroft asks where you can get a decent cup of tea

Phil Reilly Collection, Larry Crane

Although the drivers were gathered reverently around Dreyfus in Crane’s photo, it was Fangio who was the centre of attention. Fangio was remarkably humble about his own unparalleled accomplishments, yet he exuded a regal presence that inspired many of his rivals to defer to him as ‘Mr Fangio’. At one point, Earle asked Bugatti restorer Bob Seiffert, who’d attended school in Mexico, if he’d serve as Fangio’s translator. “That was like asking me if I’d take care of the King of England,” Seiffert recalls.

That night, all the drivers (except Moss, who had another commitment) got together again for dinner. At the end of the meal, Fangio rose to offer a toast. “The most important thing about racing is the friendships – not the wins, not the championships, the friendships that were established,” he said.

Earle was there. “I looked around the room and everybody’s mouth kind of dropped open,” he says. “It wasn’t just humility. It was the way Fangio saw things. He was on a plane above everybody else.”

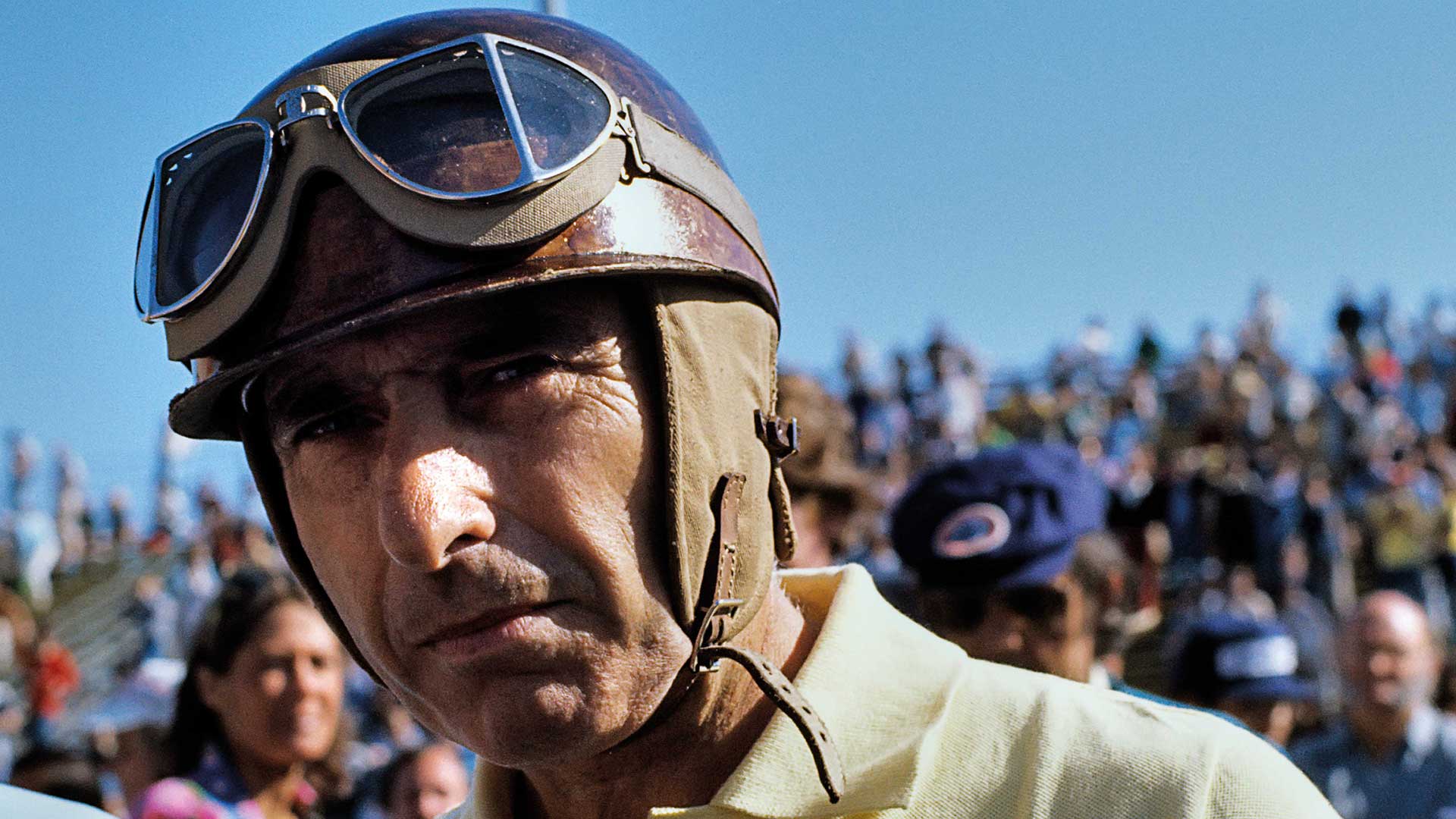

Race day dawned as a typically sun-kissed SoCal morning, and the grid looked magical. Not only did the cars evoke vivid memories of the glory days, but so did drivers dressed as they’d been back in their prime, from Fangio in a short-sleeve shirt showcasing his large, muscled arms to Dreyfus wearing a fastidiously knotted tie and pristine white coveralls to Shelby sporting the helmet battered when he crashed in the Carrera Panamericana in 1954.

Earle had repeatedly emphasised that this wasn’t supposed to be a race. It was, he cautioned, an exhibition, a celebration, a high-speed parade. The cars were to be flagged off in pairs a few seconds apart to limit the temptation for serious dicing while giving fans ample photo opportunities before the field inevitably strung out.

Carroll Shelby raced Alberto Ascari’s Ferrari from the 1952 Indy 500.

Phil Reilly Collection, Larry Crane

Fangio’s smooth pace brought a podium finish

Getty Images

Denny Hulme in an F2 Cooper.

Phil Reilly Collection, Larry Crane

Moss talks with Wheatcroft.

Phil Reilly Collection, Larry Crane

Gurney and Brabham, driving the newest cars, started first. Gurney, decked out in a Simpson fire suit, evidently didn’t get Earle’s memo about the race not being a speed contest. He dropped the hammer when the flag fell and immediately left Brabham way behind. “I don’t know what he was waiting for,” Gurney said later. “Tom [Wheatcroft] said, ‘There’s no use hanging about.’ He gets a tremendous kick out of his equipment being run the way it should be run.”

Brabham was second to Gurney, with Hulme – who’d only recently retired from F1 – a seemingly uncatchable third as they circulated past seaside flophouses and porno cinemas. Trailing blue smoke, Shelby limped home to the finish, but Hill’s Bugatti expired before reaching the end of the race. So did Moss’s Maserati, hamstrung by a misunderstanding over sparkplugs requested by Alf Francis. “The situation was nothing new,” Moss said afterwards. “I’ve broken cars before trying to catch Dan Gurney.”

“When Moss peeled off, Fangio put his race face on. It was the highlight of the weekend”

Although Dreyfus motored sedately around at the back of the pack, his performance was enlivened by Ireland’s antics. Ever the class clown, Ireland unexpectedly jumped into Dreyfus’s Bugatti right before the start to serve as a superfluous riding mechanic. He then flashed a rude salute every time he passed the pits on Ocean Boulevard and hid his eyes in mock terror as Dreyfus bent his car into the corners. “That was the worst thing I’ve ever done in my life,” Ireland reported later. “It was like a seven-lap accident.”

The night before the race, Fangio had toasted his fellow drivers as friends

Getty Images

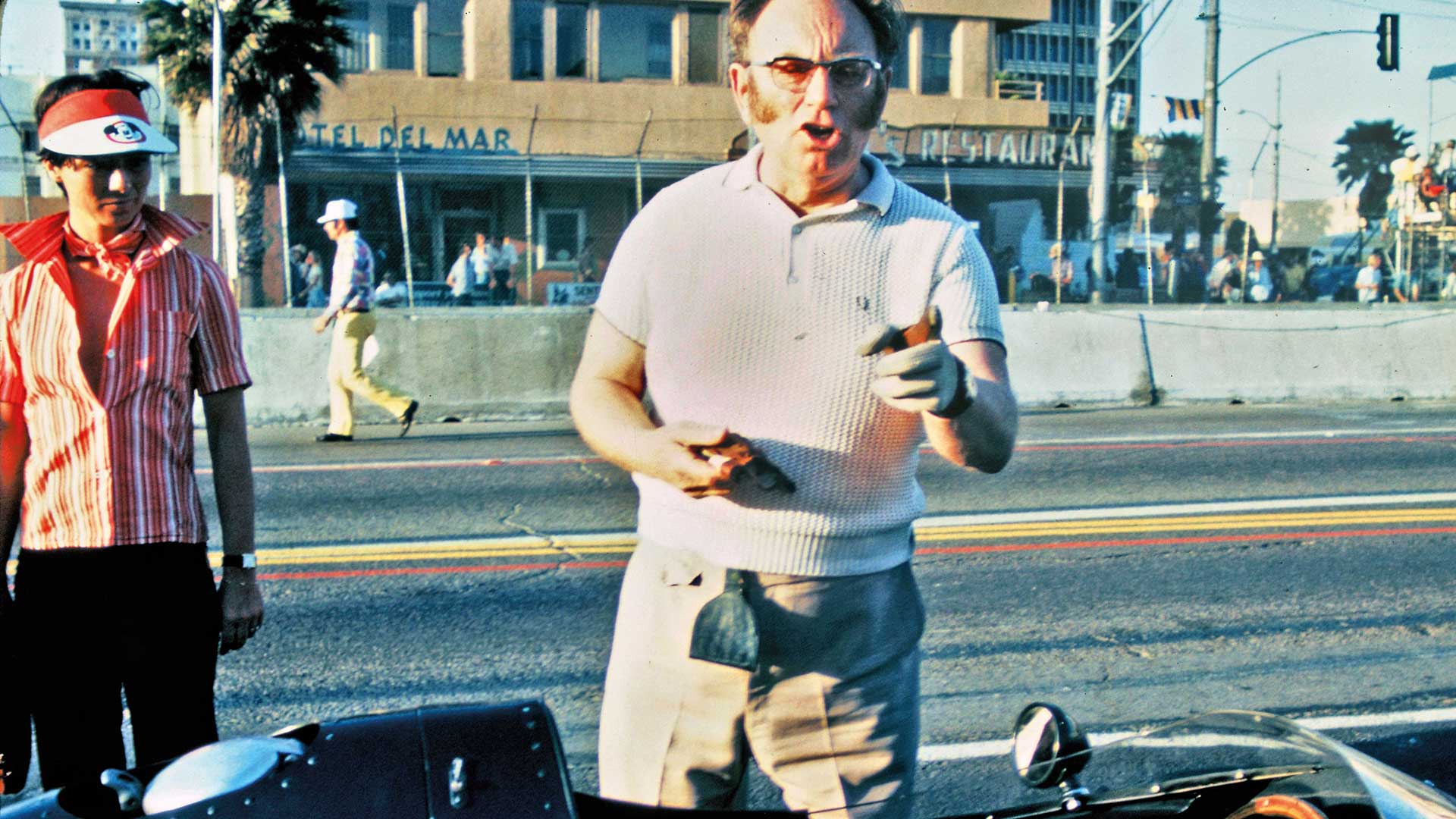

Long Beach was a run-down area in the mid-1970s, filled with low-rent cinemas and cheap hotels.

Phil Reilly Collection, Larry Crane

But the highlight of the race was more serious stuff – a performance that reminded fans of what had attracted them to racing in the first place: Juan Manuel Fangio, the Maestro, was back in the game. After several minutes dutifully running in formation with Moss’s ailing 250F, Fangio was trailing Gurney by half a lap. “When Moss peeled off, Fangio put his race face on,” Reilly says. “That was the highlight of the weekend, even more than the real Grand Prix.”

Fangio began using more revs before upshifting and venturing ever closer to the walls on corner exit. After the slower turns, he’d turn in his seat to look back at his rear tyre to see if the rubber was glazing over from wheelspin. Drifting through the faster curves, he made subtle steering corrections to prevent the tail from wagging the dog.

“I was on Linden Avenue at the bottom of the hill, and from across the street I could feel the concentration in his car,” Reilly says. “He was faster every lap but so precise that there was never anything at risk. It was amazing.”

Although Fangio passed Hulme to finish third, he couldn’t quite catch Brabham despite posting the fastest lap of the race – 1min 45sec flat, or 2.8sec faster than Gurney. Clay Regazzoni turned a lap at 1min 23.076sec while winning the F1 race from pole the next day in his Ferrari. But Fangio and company weren’t racing for championship points.

Mercedes supplied a racing crew of five for Fangio

Phil Reilly Collection, Larry Crane

Gurney won easily. “I’d never say I beat these men,” he said after spraying champagne over the victory rostrum. “It was just a thrill to be on the same course with Mr Fangio.” For his part, Fangio sounded wistful that the event hadn’t been more than a mere exhibition. As he said, “It is too bad it is impossible to turn the clock back and have a real race.”

Historic racing has come a long way since 1976. At premier events the cars are even more impressive, and the competition is far more cutthroat. Ultimately, though, are these the standards by which events ought to be judged?

By its very nature, historic racing scratches a different itch from ‘real’ racing. The goal is to recapture the beguiling allure of a bygone era. By this measure, the greatest historic car race ever was held at Long Beach in 1976. Gurney was the winner, Fangio was the star, and Chris Pook and Steve Earle were the impresarios who brought history to life.