Fangio vs Ascari — his 'greatest opponent'

In their pomp, this pair mopped up F1 titles. Paul Fearnley recounts a rivalry that captivated the world, but was cruelly cut short

Between them Alberto Ascari, left, and Juan Manuel Fangio took each world title between 1951-57.

Corbis via Getty Images

Their nicknames were El Chueco and Ciccio: Juan Manuel Fangio was indeed bandy and Alberto Ascari was… well, both were chubby in truth. Looks deceive. Though interrupted badly by injury and contract, their rivalry was the motif of the first half of the first decade of the Formula 1 World Championship. Some of its numbers are unmatched. From 31 starts apiece, they combined for 27 wins – at the top two strike-rates still – 30 pole positions and 27 fastest laps (some shared with others).

One or the other, often both, held the lead for at least one lap, often for very many more, in all bar two of the 37 Grandes Épreuves from Silverstone in 1950 to Monaco in 1955. Crunching the numbers, between them they led 66.6% of 2508 laps.

Fangio, who edges those statistics bar laps led – it’s 717 to 927, if you are wondering – is a bona fide great by most estimations; Stirling Moss reckoned him the best. But Ascari ran him very closely; Denis Jenkinson of Motor Sport reckoned him the better.

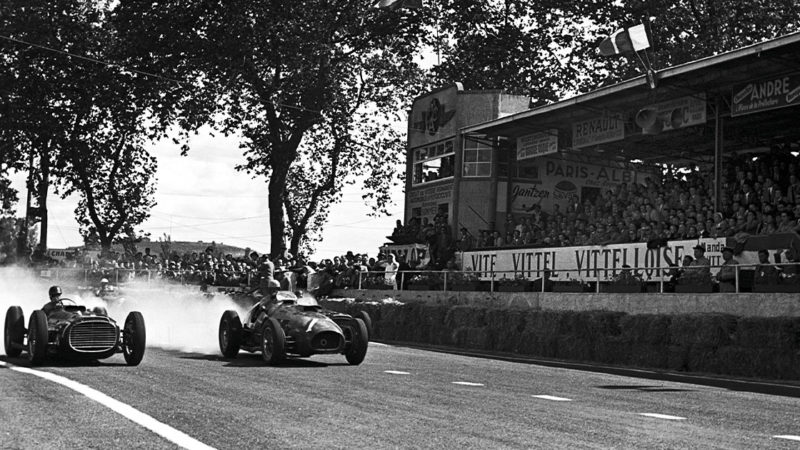

Fangio (left) racing a V16 BRM P15 and Ascari in a V12 Ferrari 375

Bernard Cahier / Getty Images

Rocket starts that left the opposition gasping and barely a mark on the road fed an innate ability to control races from the front with little apparent effort: Ascari was the prototype Jim Clark. But while Enzo Ferrari also praised that “sure and precise style”, he queried the Milanese’s “combative spirit” when not leading; whereas Fangio “never gave in”.

Friends as well as rivals – no doubt helped by their acting as team-mates only twice – Fangio’s familial Abruzzo roots and grasp of Italian eased suspicions after their first meeting in July 1948 had not gone well: not only did Fangio’s unprepossessing appearance offset an effusive introduction by Jean-Pierre Wimille at Reims, but also Ascari was too busy making his only use of the dominant Alfa Romeo 158 – he didn’t enjoy playing second fiddle to Wimille – to pay attention to the Argentine’s midfield struggle in an underpowered Gordini. (Although one needn’t have looked too closely to be impressed by his effort.)

They next met on Fangio’s home ground and in more equal equipment. Ascari, his semi-works Maserati 4CLT likely in better tune than Fangio’s, led that opening race of the 1949 temporada from start to finish. “The European stars seized the occasion to give us a royal lesson,” wrote Fangio. “Ascari – cock of the walk – driving in a way that aroused my liveliest admiration.”

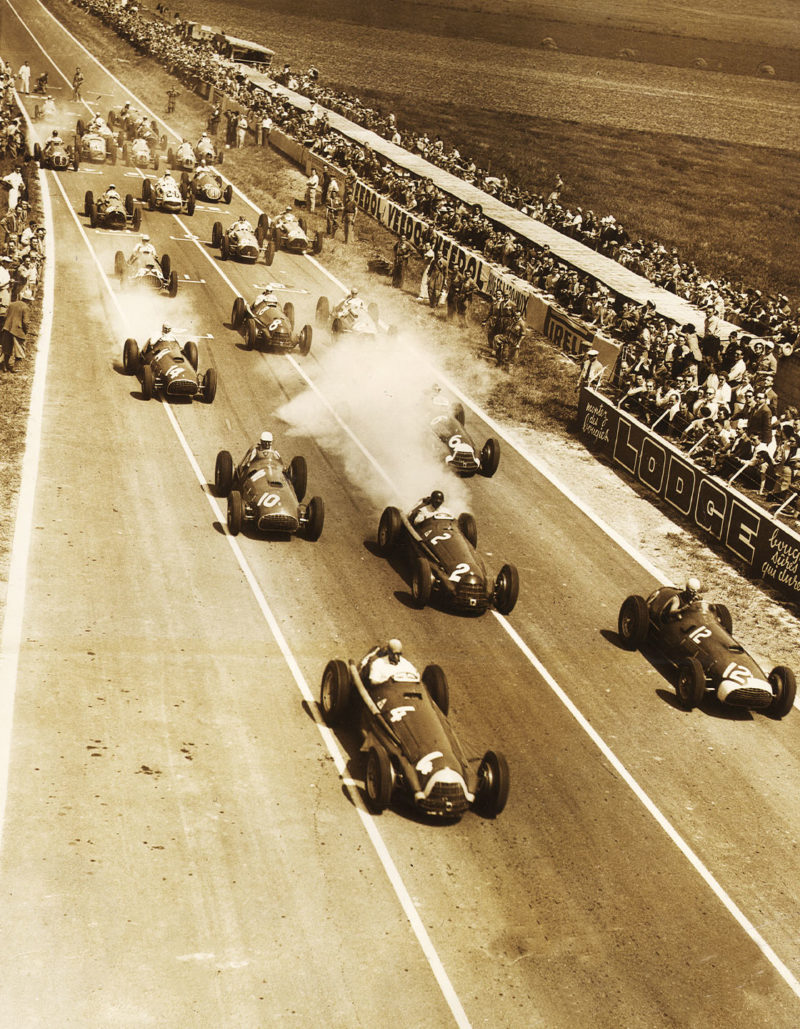

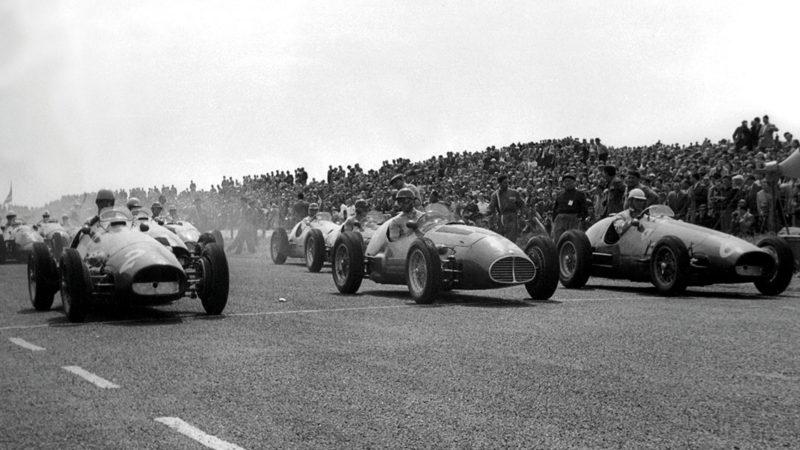

Fangio leads in the Alfa Romeo 159A (No4) from the Ferrari 375 of Ascari at the start of the 1951 French Grand Prix at Reims which, at 373.96 miles, is the longest World Championship race to date

Keystone/Getty Images

Fangio, fourth and lapped having cooked his tyres in pursuit, learnt quickly, however, and won the final round at Mar del Plata in true ‘Ascari style’. Though deafened by a split exhaust, he “felt entirely transfigured, different somehow”. By the time of their next meeting – the Belgian GP in June – the newcomer/incomer was firmly established in Europe and being courted by Ferrari.

The Monza GP, also in June, was a Formula 2 affair of more than 300 miles. Fangio’s government had bought him a Ferrari 166 F2 and with it he beat four works examples, including Ascari’s. He did so by hanging back – not knowing the circuit and having suffered transmission woes in practice – and letting the locals butt heads, before striking with the fastest lap and then coping with an overheating engine and collapsing rear wheel. This brilliantly calculated victory on a ‘fast track’ rather than a street circuit convinced him of his true worth. It persuaded Alfa Corse, too.

“The European stars seized the occasion to give us a royal lesson”

Thus Ascari at Scuderia Ferrari would be up against it in 1950 – once Fangio had conquered first night’ nerves; it was the former who crashed out giving chase in April’s San Remo GP as the latter’s victory silenced any remaining hecklers. Refettled during its 1949 sabbatical, the Alfetta was clearly the faster, particularly in Fangio’s hands (although it was team-mate Giuseppe Farina who would muster sufficient speed, experience and good fortune to become the inaugural world champion.)

Unable to beat Alfa Romeo at its supercharged game – while calculating that the Alfetta was nearing the end of its development tether – Ferrari technical director Aurelio Lampredi persuaded Enzo to follow a new path: a normally aspirated V12 requiring lighter fuel loads and fewer refuelling stops. This was achievable even in its ultimate 4.5-litre form – after increments of 3.3 and 4.1 litres – because its boosted, bloated rival was having to ‘shotgun’ methanol just to stay cool.

So equipped, Ascari would lie only two-tenths off Fangio’s pole position for September’s Italian Grand Prix at Monza and lead for two laps before his engine burst. Thereafter he charged to second place (behind Farina) having commandeered team-mate Dorino Serafini’s car. It was game on for 1951!

Alfetta by now had upwards of 400bhp – from a 1.5-litre twin-cam straight-eight designed in 1937! – but at a cost of 1.6mpg. Ferrari’s simpler chain-driven SOHC unit was perhaps 30bhp shy, even in twin-spark form, but delivered its power more smoothly to a stiffer chassis under less strain, which thus handled and stopped better while being kinder to its tyres.

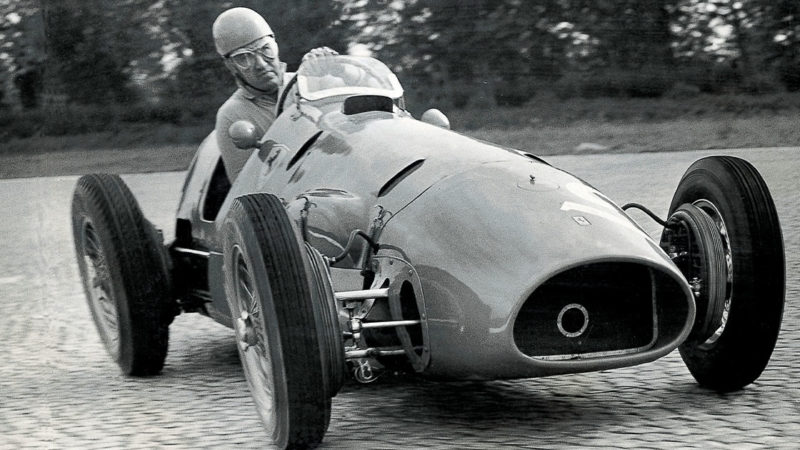

Fangio in 1951 – the first of his five title-winning seasons.

DPPI

Fangio would have to compensate for a packaging deficit. He was superb in winning the Swiss GP on the cobbles of Bremgarten made slippery by rain so heavy that the organisers considered stopping the race. He had just taken charge of the Belgian GP when a wheel jammed at a pitstop. And he drove like the devil to win the French GP in suffocating heat.

Ascari finished second at Spa and Reims.

Speeds were increasing upward of 180mph as their duel intensified – both men had to resort to a second car to reach the finish at Reims – but Ascari, though very superstitious and reportedly prone to stomach ulcers and insomnia, appeared calm. Fangio, quiet and undemonstrative, too, and (slightly) less superstitious, was making his car go faster than it cared to, with all the unsettling, juddering stresses this called into effect.

“Running away with the German GP, a wheel detached at 140mph”

But there was room neither for hesitation nor doubt. Flat out. Winning, whatever it took: cooked engines, fried brakes, pulverised drivers (even those with useful natural padding). For those Alfa Romeo demos were long gone.

The apparently inevitable happened at Silverstone’s British GP in July. The shock was that it was José Froilán González who opened Ferrari’s account – with gusto from pole and despite an older-spec engine.

Ascari promptly reasserted his hegemony by winning the German GP at the Nürburgring – a comprehensive victory from pole that allowed for a late stop for tyres. He won the Italian GP, too – four Ferrari 375s in the top five! – and the momentum was with them in Barcelona for October’s showdown. The gap to Fangio was two points and dropped scores – only the best four from seven rounds to count – lay in Ascari’s favour.

Ascari in 1953 at Monza, the year in which he successfully defended his crown

DPPI

Alfa Romeo, under the pump, resorted to mind games: word spread that yet more tankage would enable the Alfetta’s ultimate M – for Maggiorata – iteration to race non-stop. Ferrari’s gamble in response was a 16in rear wheel for better acceleration. This worked during practice – Ascari was on pole – but warning signs had been ignored and Pirellis chunking in the early laps sent every Ferrari scuttling for new rubber, of a taller size. Fangio, stopping twice for fuel, took the victory and the world title. Though Ascari’s time was soon to come, this rivalry had had its day of days already.

The World Championship’s enforced switch to Formula 2 regulations in 1952 – Alfa Romeo had withdrawn; BRM dithered; and Ferrari was content to win more while spending less – was retrograde in terms of spectacle even before Fangio’s accident. After a fraught and rushed journey from Dundrod – “You look tired,” said Ascari – including crossing the Alps overnight in a borrowed Renault, he had arrived mere hours before his debut with Maserati at the non-championship Monza GP in June. Starting from the back, a crash on the second lap broke his neck. Sedated for days, he spent weeks held rigid by a body cast and would be months in recuperation.

Unchallenged, Ascari won all six GPs he contested that season – five from pole and usually by leading every lap. The glimmer provided by González at the Italian race, sharing fastest lap and leading the first 36 laps in the six-cylinder Maserati A6GCM, on half-tanks admittedly but evidently improving and faster in a straight line, highlighted the pressing need for Fangio. His return to fitness and racing in 1953 was anticipated eagerly. Yet Ascari continued to hold sway, extending his run of World Championship GP victories to nine. The updated Maserati had the speed – Fangio started the Belgian and Swiss GPs from pole – but lacked the reliability of Lampredi’s neat Ferrari 500 ‘four’.

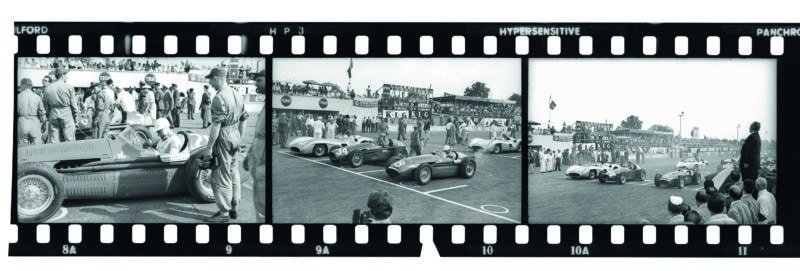

the grid at the 1954 Italian GP at Monza, with Fangio (16), Ascari (34) and Moss (28). Note Fangio’s Mercedes-Benz W196 streamliner

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Ascari’s incredible run was ended at Reims in July. That it was inexperienced team-mate Mike Hawthorn who ended it – outmanoeuvring Fangio on the last lap by using his Ferrari’s superior brakes and acceleration – was an even bigger shock. Pole-sitter Ascari had been in the mix throughout yet led not a single lap in finishing fourth. Had he become complacent?

Be assured that he was hungry. He dominated the subsequent British GP. Running away with the German GP – he was the undisputed master of the Nürburgring – the right-front wheel detached at 140mph. And he overcame a long delay because of a carburetion issue – a mechanic unblocking a jet with a few mallet blows! – to win the Swiss GP. At Silverstone, he had set a new lap record on full tanks and piled on the speed despite almost a minute’s lead and a late burst of hail. At the Nürburgring, he had rejoined the fray and broken the lap record despite that earlier fright; he would beat it again having switched to a team-mate’s car. And at Bremgarten, he had ignored ‘EZE’ signals to secure a second world title.

At the Monza finale, with (apparently) nothing to lose, Ascari fought tooth and nail against Fangio – plus Ferrari colleague Farina and Argentine Onofre Marimón’s delayed and oft-lapped Maserati – each with their own agenda, none of them helpful. Having held the lead most often as it (officially) changed hands 19 times, he spun at the final corner for reasons debated still. Fangio, blessed with a sixth-sense and the wilier in such situations, slipped through to victory. Ascari had rolled the dice – and lost.

Snapshots of snap decisions often linger longer than the bigger picture and frustratingly he would be allowed few opportunities to alter loosely gathered perceptions tightly held.

Wooed by the charm and chequebook of Gianni Lancia – and the promise of a world-beating GP car for the resumption of F1 – he jumped ship for 1954. He sank almost without trace. He may have been expensive, but talk was cheap: Vittorio Jano’s ambitious design ran very late despite a gradual simplification of its original concept. So restricted to the marque’s concurrent sports car programme – in which he won the Mille Miglia and proved more than a match for rare team-mate Fangio at Sebring and Dundrod – Ascari was forced/allowed to moonlight for Maserati and Ferrari in order to stay single-seater sharp.

Ferrari’s Ascari (No2), Maserati’s Fangio and Nino Farina, also of the Scuderia, take the front line at the 1953 Dutch GP. Ascari led from start to finish

Bernard Cahier / Getty Images

Fangio, too, had swapped teams. Joining Mercedes-Benz after winning the Argentine and Belgian GPs for Maserati, and having refused a generous offer from Lancia – he had a knack for choosing the right team at the right time – his debut victory aboard the streamlined W196 in the French GP at Reims caused a sensation that tingles still.

But Ascari, on his first acquaintance with Maserati’s 250F, had shone brightly, too, albeit briefly. Within two laps he was plunging over the crest into the fast right-hander after the pits without lifting; even Fangio was feathering. ‘Jenks’, though conceding that the latter’s approach speed was likely faster, wrote: “It is an interesting sidelight on the two acknowledged masters that both were in a strange motor car and yet without any hesitation they were lapping faster than anyone.” The big difference was that Ascari’s transmission failed at the start, while Fangio benefited from his team’s meticulous preparation.

“Fangio’s affinity with Ascari was stronger than his with Moss”

Not everything was rosy at Mercedes-Benz, however, and Fangio was again making a racing car look better than probably it was. He was not unbeatable. If only Enzo had paid more. When returnee Ascari rolled into Monza’s pits, the engine of his Ferrari 625 a victim of a missed downshift, the look he gave wife Mietta spoke volumes. A fierce battle with Fangio and the Maserati of Stirling Moss had seen Ascari lead the majority of the first half of the Italian GP. Clearly a precious chance had slipped his grasp. Nobody could know how precious.

When Lancia’s D50 finally arrived, in time for the Barcelona finale, it proved skittishly fast – Ascari, treating it like a test session for 1955, grabbing pole by 1sec from Fangio and pulling away at 2sec per lap – until its clutch failed after nine laps. Hawthorn’s suddenly much-improved Ferrari 553 won the race, while world champion Fangio finished third in a deeply troubled car. If only Lancia had got its act together sooner.

Ascari’s final F1 race was at Monaco in 1955 in the Lancia D50 (No26). He’s flanked by Fangio and Moss at the start of the race but later crashed, possibly suffering concussion.

Yves Debraine: Klemantaski Collection: Getty Images

Thorough Mercedes-Benz and quixotic Lancia were equal in terms of speed at the start of the 1955 World Championship – the stopwatch could not separate Fangio from Ascari at Buenos Aires nor Monaco – the D50 remained tricky at the limit; Ascari spun on several occasions during practice in Argentina and crashed out of the race before quarter distance, having battled eventual winner Fangio for the lead.

The might of Mercedes-Benz was beginning to tell, too. Its bespoke production of a short-wheelbase car with outboard front brakes, a layout better suited to Monaco’s demands, put Lancia on the back foot and Ascari, soldiering on, would be almost a lap behind when he suffered the most spectacular crash of his career. Had he completed that lap he would have taken the lead, for Moss – now at Mercedes as the final piece of its superteam – had just joined Fangio on the sidelines because of a copycat failed locking nut in the desmodromic valve-gear. Instead, Ascari lost control on oil, likely dropped by Moss’s smoking car, clipped the chicane and dived into the harbour. He was lucky to bob to the surface with only bruising and a broken nose.

Did he suffer undiagnosed concussion, too? Four days later he crashed a Ferrari sports car at Monza in trifling circumstances but with tragic consequences. He was 36.

The BRDC Trophy at Silverstone in 1950 with, from left, Ascari, Italian driver Dorino Serafini, Fangio and BRM’s PR man AF Rivers-Fletcher

Klemantaski Collection/Getty Images

Fangio had lost his “greatest opponent”: “I deeply admired the graceful and pleasant style of Alberto’s driving. A real champion.”

They had shared a lot in their 61 races (including heats) against one another: 40 pole positions, 33 wins and 34 fastest laps. Of those, 22, 17 and 22 belonged to Fangio. Was the latter stat indicative of his crucial final tenth – or symptomatic of Ascari’s knack of winning at slower speeds? Probably both.

Though those figures are impressive – and confirm Fangio’s assumed advantage as being narrow – the relationship went deeper. Other numbers mattered as much, if not more. Separated by ‘only’ seven years and having both lost five to a global conflict, Fangio’s affinity with Ascari was stronger than his with the much younger Moss. Battles against the latter were transitional. Those against Ascari had been fundamental.

Moss symbolised the next generation. The size of the gap which he eventually put between himself and the second best is attributable not only to his genius but also to the void left by Ascari’s death.