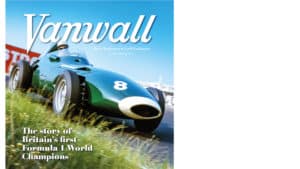

Vanwall book review: the start of something green

A radically revisited volume applauds a man and a team who put Britain on top of the world, says Gordon Cruickshank

Vanwall team boss Tony Vandervell stands by Lewis-Evans’ car at Pescara in 1957

Grand Prix Photo

There’s a photo in here which made me blink when that page fell open – the life-size face of Jenks gazing at me with those shrewd eyes. It took me back to times in the office when he was carefully explaining something to me about Altas, or why all Bugattis were fakes unless he said otherwise. He and historian Cyril Posthumus were the perfect pair to write this book back in 1975; both thorough, painstaking over details, and both on hand, attending Vanwall’s races and hearing first-hand about the tribulations of creating a grand pre-winner. In this new edition the text is as the original but the scope is considerably greater, with fresh, stylish presentation, generous photos, and Doug Nye on hand to annotate the images with facts and pithy comment. Of a photo showing Raymond Mays and Peter Berthon, parents of the over-produced BRM, he says Vandervell “quickly got their number”. Another showing the bulky Froilàn Gonzàlez recalls a time “when the drivers were fat and the tyres were skinny”.

This enhanced edition is a fine tribute to the cars which as Tony Brooks, last remaining Vanwall driver, says in his foreword “fired the starting pistol of Britain’s domination”. Following Brooks’ own GP win two years before, the Brooks/Moss Aintree victory in 1957 released Britain’s war-weary brakes, leading to a historic manufacturers’ title. Soon Cooper, Lotus and a rejuvenated BRM would be showing the way – which is just what industrialist Tony Vandervell wanted to see, and why the book was dedicated to him. His tough and demanding character comes across clearly in the writing, with a good deal on his early life, his own racing and the clever deals over his bearing system that made him rich.

Goodwood 1954: Collins wields the Thinwall Spl, by now almost a Vanwall

Klemantaski Collection/Getty Images

Not having seen the original I could treat this as a completely new work, and it’s a grand example of engineering and racing research that will expand your knowledge. Fascinating to learn of the bureaucratic juggling over the purchase of that first Ferrari in 1949 and the edgy interchanges with Maranello over dubious build standards. “Please do not accuse us of poor presentation,” reply Ferrari. That machine became the Thinwall Special, initially to assist BRM development, a plan which soon expanded into Vandervell’s own grand prix effort to boost Britain to what he felt was its rightful place at the top of the grid.

In detail the respected authors expound the story of Norton’s place in the CAV empire and how its technology extracted so much power from the Vanwall’s four cylinders, the tension between BRM’s Alfred Owen and Vandervell, and the irritable telegrams between Tony and Enzo – the irresistible force goading the immovable object.

“Tony Vandervell had taken motor racing by the scruff of the neck and given it a thorough hiding”

Doug Nye inherited the Jenkinson and Posthumus archives and they’re put to excellent use here. It’s one of the gems of the book – dozens of spreads of documents: letters from Ferrari, notes from Hawthorn, telegrams, a plea from world champion Farina for his starting money, all displayed with their tatters, scribbles and thumbprints. Reproduced pretty much full size, we can read Moss’s thoughts on car development, or enjoy a dispute over Alberto Ascari’s availability for the car’s 1954 debut. There’s even a letter to Jaguar asking if they can “knock up” an aerodynamic body. That of course came to nothing when Colin Chapman and Frank Costin came on the scene, resulting in the sensational teardrop cars that showed the rosso corso machines the way home. You’ll be halfway through this book before the teardrops arrive, a reminder of the huge amount of development work that had already gone on.

The book doesn’t stint on the photographic menu, fielding a wealth of images of workshop, pits, and people with plentiful racing, making Vanwall visually absorbing as well as informative. Some of the colour is sensational, and being written nearer the events the facts are broadly firsthand, especially from the boss himself. Considering employing Wolfgang von Trips just a decade on from the war he writes to Moss, “I’d get no medals for employing a German driver.” To a journalist quizzing him about the rumoured new car he says, “I look forward to your telling me more about it than I know myself.” It becomes clear that he and Ferrari were similarly driven, both uncompromising and bullheaded, dedicated to racing above all and sparse on praise. There’s also a wry comment, presumably written by Jenks himself, that, “A suggestion by Denis Jenkinson that he should write the Vanwall story was politely brushed aside.” This despite being the team’s lap-charter in 1958.

Sadly, glory brought tragedy in its wake when in 1958 Stewart Lewis-Evans, aged just 28, died in a Vanwall in the same Moroccan race that sealed their manufacturers’ championship. It absolutely floored an already worn-out Vandervell who effectively retired, deflating the team overnight, though as a fantastic picture of Tony Brooks at Aintree in 1959 reminds us there were a few later entries and even a lovely lowline prototype for 1960. But without its “Churchillian” leader, the drive had gone. “Tony Vandervell had taken motor racing by the scruff of the neck and given it a thorough hiding,” say the authors. As I know, Jenks could be hard to please but I think he’d look at this and say “not bad at all”.

Vanwall

Vanwall

Denis Jenkinson & Cyril Posthumus with Doug Nye

Porter Press, £90

ISBN 9781913089252

Vanwall

Vanwall