Jackie Stewart tells how Tyrrell beat the world from a Surrey shed

While Ferrari and Lotus had the luxury of racing tracks near their engineering sites, at Tyrrell the set-up was less sophisticated. Simon Arron speaks to Jackie Stewart about the Surrey team’s extraordinary climb to the top of the world from a timberyard

Tyrrell shed in 1971

Grand Prix Photo

More than 20 years have passed since its name last appeared on a grand prix entry list – and almost 40 since its most recent victory. For many, the Tyrrell Racing Organisation remains an institution, a symbol of a lost age wherein it was possible to build your own Formula 1 car and conquer the establishment. Little more than 50 years ago, Tyrrell secured the constructors’ championship for the only time – and in its first full season, too. “That was a big deal,” says the team’s talisman Sir Jackie Stewart, “and all the more so when you consider the team was run from a shed.”

F1 teams were significantly smaller back then (“We had seven mechanics to run two cars,” Stewart says), but serial world champions Lotus and Ferrari had their own test tracks within a stone’s throw of their factories. Ken Tyrrell? He was happy to operate from a woodshed that had previously been used by his family’s timber business.

The decision to become a constructor came about through circumstance. Stewart clinched the first of his world titles in 1969, at the wheel of a Tyrrell-run Matra, and the French firm wanted the partnership to continue the following season… on condition that the team switched from Cosworth V8 power to one of its own V12s.

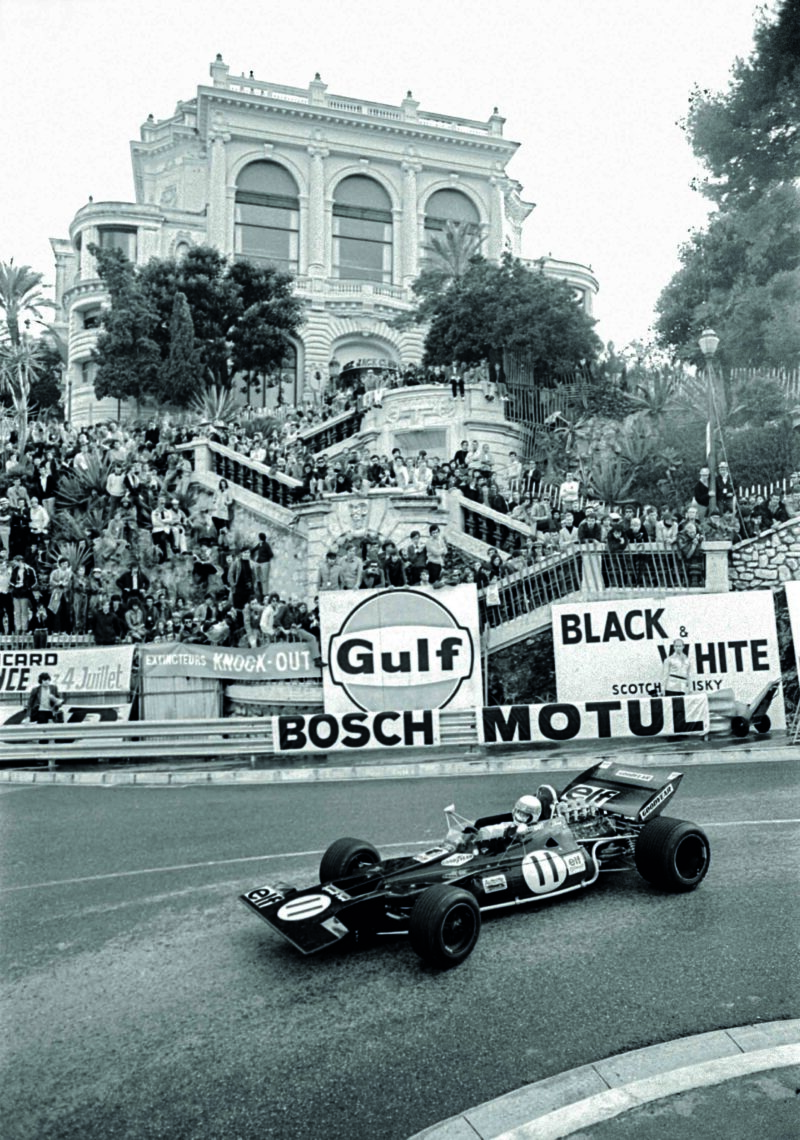

“One of my better performances”: Jackie Stewart in the Tyrrell 001, Monaco Grand Prix, 1971.

Klemantaski Collection/Getty Images

“Ken and I both felt it would be better to stick with Cosworth,” Stewart says, “and I had absolute confidence in its engine. It was great, because although quite a few teams were using Cosworths there were no unfair advantages – the engines were all the same. Colin Chapman had helped to bring Cosworth into F1 with Lotus, but even he didn’t receive special treatment. I did try the Matra V12 – we tested it in secret at Albi, at something like two in the morning. It sounded absolutely wonderful, but just didn’t quite have the Cosworth’s bite.”

The next hurdle would be finding a chassis for Tyrrell’s engine of choice.

“The problem,” says Stewart, “is that established manufacturers wouldn’t sell to Ken. We had dominated with the Matra the previous season, so Lotus and Brabham didn’t want to run the risk of being beaten by their own car. But March Engineering had just been launched and was building chassis for several categories, including F1, so that became our only option.”

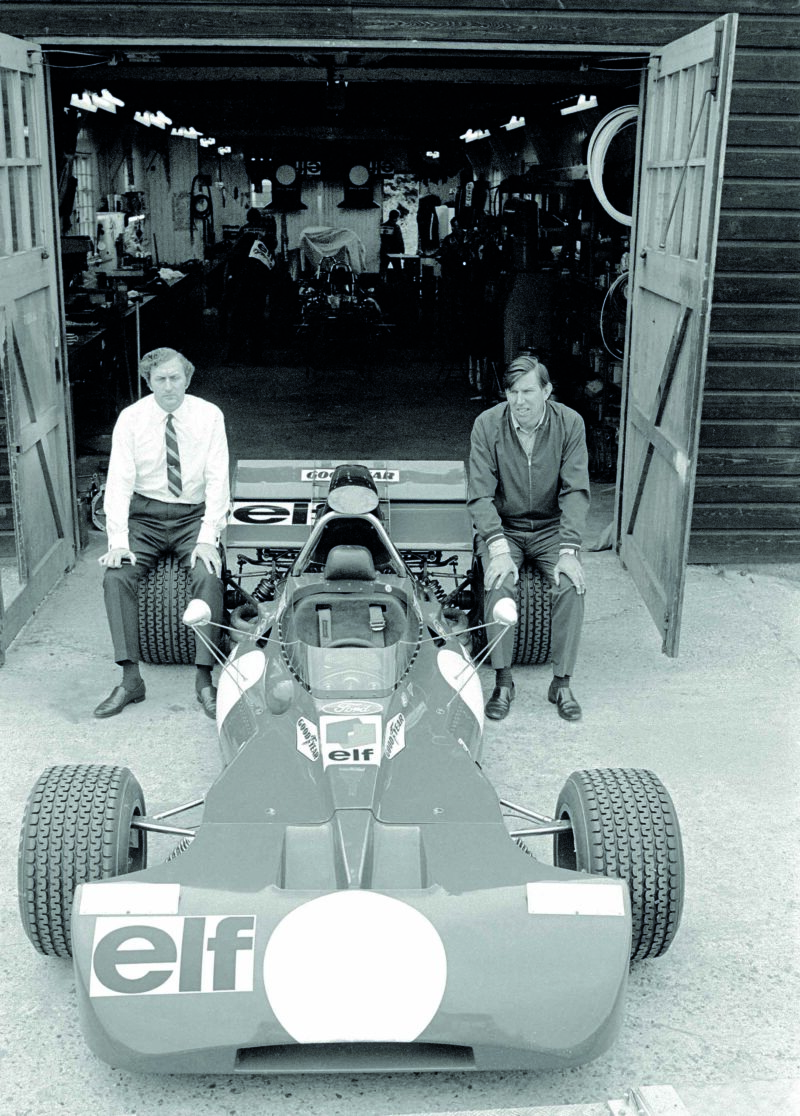

Tyrrell designer Derek Gardner, Stewart and Ken Tyrrell with the 003 outside the Shed in summer ’72.

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Stewart qualified his March 701 on pole for the season-opening South African GP in 1970, finishing third, won the Race of Champions at Brands Hatch, took second to the works 701 of Chris Amon in Silverstone’s International Trophy and won again at Jarama, Spain, in the second round of the world championship – the last such success for a privately entered customer chassis.

“Fundamentally the March wasn’t a bad design,” Stewart says, “but it was not a good car. It was reasonably competitive, but it wasn’t friendly to drive and nor was it terribly reliable – there was nothing wrong on the mechanical side, but the cars weren’t particularly well built. I don’t know whether it was a result of the cost of setting up a new business, but some of the components felt as though they’d come from the poorest quality road cars – something like a Hillman Imp!”

March 701, 1970 South African GP

Such was the trigger for Tyrrell deciding to become a constructor in his own right.

“I’m not sure quite when he took that decision,” Stewart says, “but he didn’t tell anybody – not even me, at least initially. He was always very cautious about things like that. But it was a huge commitment.

“Not long after he’d confirmed to me what he was doing – very quietly! – I was dispatched to [designer] Derek Gardner’s house near Leamington. He had an attached garage and inside was a wooden mock-up, so I was asked to go and check the seating position and so forth. That was the first time I laid hands on it.”

he 001 debuted at Oulton Park in 1970, with Stewart claiming fastest lap

Tyrrell 001 made its race debut in the Oulton Park Gold Cup on August 22, though the team took along its March as a spare. “Ken was very friendly with the circuit manager, Rex Foster,” Stewart says, “and managed to negotiate some exclusive track time before the race. I could tell straight away that the car was a big step forward – it felt completely different.

“It wasn’t a particularly easy car to drive, because Derek favoured a short wheelbase and that made it extremely nervous at some circuits. I was chatting to Emerson Fittipaldi about this not long ago and he said he was never sure how I managed to drive the thing, but it was definitely quick.”

Fast, perhaps, but not yet flawless. Teething troubles prevented Stewart from recording a time with the Tyrrell during practice at Oulton, when he lapped quickly enough in the March to secure a place on row two, but he opted to race the new car from the back of the grid. A sticking throttle stifled his early progress, but the car’s potential was obvious once it was running cleanly – not least because he sliced 2sec from the lap record he had set one year earlier in the Matra. Reporting the event in Motor Sport (October 1970), Denis Jenkinson wrote: “Although the debut of the new Tyrrell car was fraught with troubles, the result was impressive for Stewart flung it around the circuit with great confidence, displaying the artistry of driving that has been lacking with the March recently.”

Stewart in Spain, his only win in 1970

Grand Prix Photo

Tyrrell works, ’71

Grand Prix Photo

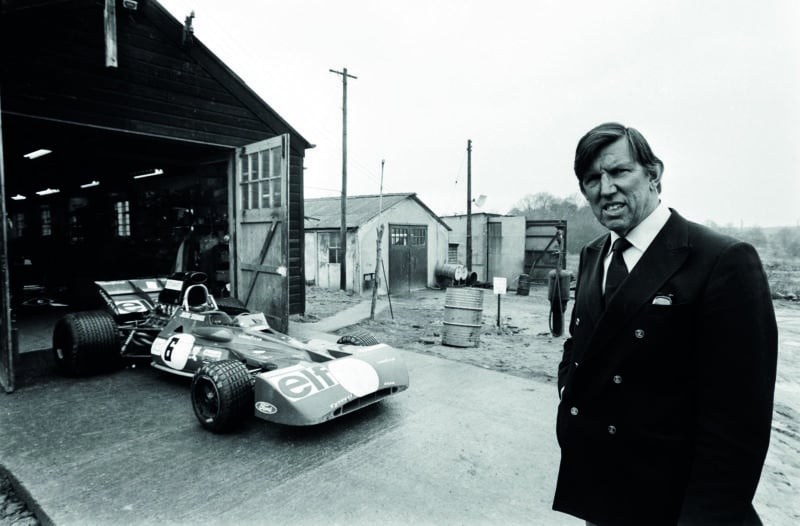

Stewart’s 006 in the Tyrrell yard before the 1973 BRDC International Trophy – which Stewart won

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

That had been a non-championship race with a small field of grand prix cars bolstered by F5000 machinery, but confirmation of the new combination’s potential followed one month later. The Tyrrell made its world championship debut in the Canadian GP at Mont-Tremblant, where Stewart took pole and led comfortably until his front-left stub axle failed on lap 32. A fortnight later, Stewart qualified second for the seasonal finale at Watkins Glen and this time led for 82 of the 108 laps, but an oil line worked loose – the consequence of one of its retaining tie-wraps having melted – and after a few smoky laps the Scot ground to a halt, out of oil. Such growing pains would not endure.

“Ken chose the right people and knew how to look after them”

Stewart finished second to Mario Andretti when the 1971 campaign began in South Africa, having taken pole, but then won five of the next six races before adding a further victory in Canada. Across 11 races, he netted six wins, one second and a fifth, putting him 29 points clear of closest challenger Ronnie Peterson.

“Monaco that season was definitely one of the highlights,” Stewart says, “because my rear brakes failed just before the start and we didn’t have time to repair them, so I had to manage the whole race using the fronts alone – definitely one of my better performances.”

Stewart’s second of five wins in 1971 came here at Monaco

Cevert and Stewart before the 1972 Belgian GP

He won at the Nürburgring, too, the second of his three German GP victories. The track’s poor facilities had been highlighted at the time by Stewart, part of his crusade to make the sport safer, but it was back on the calendar in ’71 after an upgrade-enforced sabbatical. For all that he was wary of its perils, however, Stewart was a master of its contours.

“That makes no sense, does it?” he says. “I’m a severe dyslexic. I can’t read my own name on a keyboard, I can’t find my name on a telephone, I don’t know the alphabet – or the national anthem, come to that – yet I could remember every inch of the Nürburgring. Almost to this day, I could tell you about every corner and every braking distance – it’s totally contradictory, because that shouldn’t be possible, but I had complete confidence there.”

He retired from the Austrian GP with a broken halfshaft, but other results that afternoon ensured the title would be his. Engine failure forced him out of the following race at Monza, too, but team-mate François Cevert took third, and Tyrrell was now unassailable as leading constructor.

Gardner and Tyrrell at the factory

Klemantaski Collection/Getty Images

“Of my three championship victories,” Stewart says, “I think this probably was the most special because it was Tyrrell’s first full season as a manufacturer. I think it was one of the most impressive things in the history of motor sport. I mean, it wasn’t like Mercedes-Benz, Auto Union or Alfa Romeo coming in. This was a very competitive period and we ran our cars from this little wooden shed, managed by somebody who was really a timber merchant.

“But one of Ken’s great skills was choosing the right people and knowing how to look after them, so they were absolutely loyal to him all the way through. He organised life and medical insurance for them, for instance, and no other team did stuff like that in those days.

“I know we had a few reliability problems when the Tyrrell first appeared, but once those were sorted the cars were quick and consistent. As far as I was concerned we had the best mechanics, and Ken managed them very well. He didn’t think there was anything wrong with the fact the team was based in a shed…”

This would, though, be Tyrrell’s only title as a constructor. The team remained competitive for a couple of seasons beyond the Scot’s retirement at the end of 1973, but there would be only seven more victories to add to the 16 of the Stewart era, the last of those recorded by Michele Alboreto in the 1983 Detroit GP. The team was sold in 1998 to newcomer British American Racing, whose main interest was securing Tyrrell’s entry for the following season. It moved the whole operation to a new factory in Brackley that would in turn be home to BAR, Honda, Brawn and, today, Mercedes AMG.

Tyrrell’s final win came at Detroit in ’83

Grand Prix Photo

“Tyrrell could have been champion constructor again in 1973,” Stewart says. “It was nip and tuck with Lotus, but then of course we pulled out of the final race at Watkins Glen following François’ fatal accident during practice. That wasn’t a matter of nerves or fear, but simply a question of respect. It would have been wrong for me to go and drive a racing car the day after one of my best friends had been killed, but in different circumstances I think it’s a race I could have won.

“That said, on the Friday evening before François crashed, Ken had suggested that it would be a nice touch, if we were running first and second in the race, for me to pull over and let him through. I said I’d think about it, but that was quite a big thing given that it was to be my 100th world championship grand prix start – and also my last. Sadly, of course, it would be a decision I didn’t have to make.

“My wife Helen and I had been on holiday with François the week before the race and he’d been asking me whether he should accept an offer from Ferrari. I was trying to persuade him to stay, but without giving the game away that I was planning to retire as I had still to inform Helen. I’d known since April that I was going to stop, but had told only Ken and Walter Hayes from Ford. François didn’t know – and would never know – that he was about to be promoted to the role of team leader…

“In the end I started 99 races and won 27, so my batting average wasn’t too bad. It was nothing like Lewis Hamilton today, of course, but Ken Tyrrell was operating from a wooden shed with a handful of people. And I can’t emphasise that enough. It really was a wooden shed – and it never stopped being a wooden shed throughout my time at Tyrrell, or indeed beyond. It was quite remarkable.”