Colin McRae's triumphant 1995 WRC victory

In the year that Damon Hill and Michael Schumacher had been slugging Colin McRae and Carlos Sainz were in a titanic tussle for top spot. it out in F1, over in the World Rally Championship, Subaru team-mates Anthony Peacock looks back at the season that went right to the wire

McRae in full flow

The single most striking thing about Colin McRae’s 1995 World Rally Championship title, according to nearly everyone who was lucky enough to be there at the time, is that it was more than 25 years ago. For many people, half a lifetime away. And because of that, it’s understandable that memories are patchy and some recollections gone, while others remain as vivid as if they happened a few minutes ago.

A bit like flicking through an album where an assortment of the photos are missing, the souvenirs of that season are a patchwork kaleidoscope of moments, not necessarily in chronological order, which combine to give a nostalgic flavour of what actually happened.

But most people already know the basics of the story. The wave of expectation that preceded the start of that 1995 season, a cut-throat year-long battle with Spain’s Carlos Sainz, and a finale which was the rallying equivalent of 1976 in Formula 1. A showdown between two maverick geniuses that turned into a resounding British triumph.

Pressure at Rally Catalunya

McKlein

What’s perhaps even more interesting is how the passage of time has altered the perceptions of McRae’s achievements. For the people who were there, perspectives have subtly changed, from being caught up in the moment to looking back on an enduring feat that defined so many lives and careers.

Back then, like all good times, there was a feeling that everything was going to last forever. It was the height of the Group A era, with manufacturers – notably Subaru – coming into the sport and Colin’s star shining as bright as the Pleiades star cluster that inspires the famous Japanese manufacturer’s logo.

“It was a showdown between two maverick geniuses”

McRae had enjoyed an excellent 1994 season – his first proper full year in the world championship, which resulted in two wins: New Zealand and Rally GB (or the RAC as it was known back then). The Impreza was new, and only expected to get better the following year, with Prodrive working flat out to create a world-beater in 1995.

“There was a feeling that it was more a question of when rather than if,” recalls father Jimmy McRae, who accompanied Colin on most rounds, more as a friendly face than in any official role. “There wasn’t a lot of advice that I could really give Colin: the car that he was driving then was a bit different from anything I drove, and he was a lot faster than me! But I could be a sounding board and share ideas about tyre choice and things like that.”

Nowhere is tyre choice more important than Rallye Monte Carlo, and that actually got off to the worst possible start for McRae. Not only did he go off on the famous Sisteron stage, but his team-mate and other key protagonist of the 1995 season – Sainz – won.

“Our ice-note crew had warned us that there might be a bit of ice on the corner, but when we got there it was absolutely pure sheet ice and off we went,” remembers Derek Ringer, McRae’s co-driver. “We told Carlos what happened and he said, ‘Yes, of course, there’s always sheet ice there.’ So thanks for that, Carlos…”

Enemies in ’95 but McRae and Sainz would later become good friends

A lot has been said about the rivalry between McRae and Sainz over the years, but – at the beginning of 1995, at least – it was mostly good-natured, if indubitably tense. Probably this is the single aspect of the story that has changed most over the years. From a relationship that had seemingly deteriorated beyond repair by the end of 1995, the two gradually grew closer once more, in spite of everything that had happened. They had a towering respect for each other as team-mates once more after several years at Ford and later Citroën, and, as Sainz recounts, they became better friends than ever in the years before Colin died. It was McRae who first suggested to Sainz that he might like to consider doing the Dakar Rally, during one of their many chats.

“By the end of our 1995 season it was tense. Especially after Spain”

“In the end, Colin was my best friend in rallying,” says Sainz. “Not a day goes by without me thinking of him for some reason or other. But back then, it was a bit different. We were both younger and we both wanted to win. I was actually happy with our 1995 season, but by the end it was a bit tense. Especially after Spain…”

Sweden, the second round of the 1995 season, was a disaster for the entire Subaru team, with all three cars retiring due to engine-related issues. By Portugal in March things were back on track, but it was Sainz who was on the top step of the podium while McRae was third (which was, in reality, only his sixth career podium).

Winter wonderland at the Swedish Rally. This was round two of the 1995 WRC but neither McRae nor Sainz finished

On to the insidious Tour de Corse, and there was not much to choose between them: 25 seconds to be exact, as Sainz finished fourth ahead of McRae in fifth.

And then it was the longest trip of the year, to New Zealand – and that was the first big turning point of this epic season.

Sainz, who was leading the championship, didn’t make the 24-hour journey to the other side of the world as days earlier he had fallen off a mountain bike and broken his shoulder. Maybe it was a little bit more than a mountain bike, if the truth be told, but it couldn’t have come at a worse moment. His loss was the gain of the team’s junior driver, Richard Burns, drafted in to take Sainz’s place after finishing seventh in the Rallye de Portugal. Ultimately it would lead to disappointment, as Burns – another late, lamented champion – retired with a broken engine.

July 1995 brought the WRC to New Zealand, but with Carlos Sainz absent, McRae was free to dominate.

“Ourselves and Colin were at different stages in our careers,” remembers Robert Reid, co-driver for Richard Burns. “Out of myself and Richard, I was definitely the one who knew Colin better; at least in the beginning – I’d actually co-driven for Colin in the past, and we were both part of the Scottish ‘mafia’, which Richard was never sure about. It was interesting to watch the relationship between Colin and Richard evolve though, from Richard being the understudy to a genuine rival. Back in 1995, we were definitely the understudies. We weren’t even doing the full world championship, just a handful of events like New Zealand.”

There was no real doubt as to who would win Rally New Zealand in 1995. Having taken his very first career WRC win in the land of the long white cloud with the Subaru Legacy two years earlier, then dominating again with the Impreza in 1994, McRae was on an absolute mission to make it a hat-trick.

He duly won 10 of the 33 stages to score maximum points, and it was then that he – along with most of Britain – realised that the championship was a genuine prospect that year. Some people have said that Sainz falling off his bike was the turning point of the season, that things might have perhaps worked out differently had the Spaniard been able to recover slides on two wheels as effectively as he did on four. But that is just not true. New Zealand was a foregone conclusion before Colin’s plane had even touched down in Auckland.

“Few could have predicted how toxic the championship was to become”

And then came the Network Q RAC Rally, with Sainz, pictured here at Tatton Park, and McRae both on 90 points

“The real pivotal moment was probably in Australia instead,” says Derek Ringer. “New Zealand didn’t make much difference as Colin would have won anyway. But in Perth we were involved in a close fight for the win with Kenneth Eriksson in the Mitsubishi, and in the end – although most people think it’s not really like him – Colin quite wisely decided to settle for second place and bank the points. I can’t claim credit for that or say that I talked him into it: it was Colin’s own decision to do that, and I think that was where the tide really began to turn.”

It meant he left Australia with a five-point lead over a fully recovered Sainz, with just two rounds of the championship left to go: Spain and Britain. A film director couldn’t have staged it better. The scene was set for something epic. But few people could have predicted just how toxic or controversial it was to become.

Sainz, the Matador, swaggered into home territory, an intense, wired man with flashing eyes, the worship of an entire nation behind him, and the most ferocious work ethic that has ever been seen in rallying. He would test and prepare until his fingers bled. Above all, he had to win at home, in order to ensure a comfortable margin over McRae before taking on the Scot again at Rally GB, where McRae had won the previous year.

Subaru team, Spain

A lot has been said and written about what happened in Spain in 1995. It was a complicated event, made that much more controversial by Toyota’s subsequent disqualification for trickery involving a turbo restrictor, and Subaru had decided that its best hope for victory and maximum points lay with Sainz. Team orders were issued to make it happen, but McRae – who was pushing hard for the win – didn’t see it that way.

Team members were even dispatched to the stages to slow Colin down, but it was only the threat of an instant sacking that convinced him to settle for second place behind Sainz at the very last gasp. He’d go into the final round of the championship equal on points with his team-mate. But the fallout had been sufficient to terminally damage the relationship between Prodrive and Sainz, who would head off to Ford in 1996.

Even though it was the Spaniard who had ultimately benefited from this messy situation at home, he was the one who seemed more rattled going into the title decider. And there was no doubt where the loyalty at Prodrive lay.

“In the end, Carlos actually did Colin a favour with everything that happened in Spain,” concludes Jimmy McRae. “He wasn’t really that upset by it all, but he was extremely determined to go one better on the RAC. It was from that moment on that we all knew he was going to do it. He was just unstoppable. Of course, that’s really the part of the season that everybody always remembers now.”

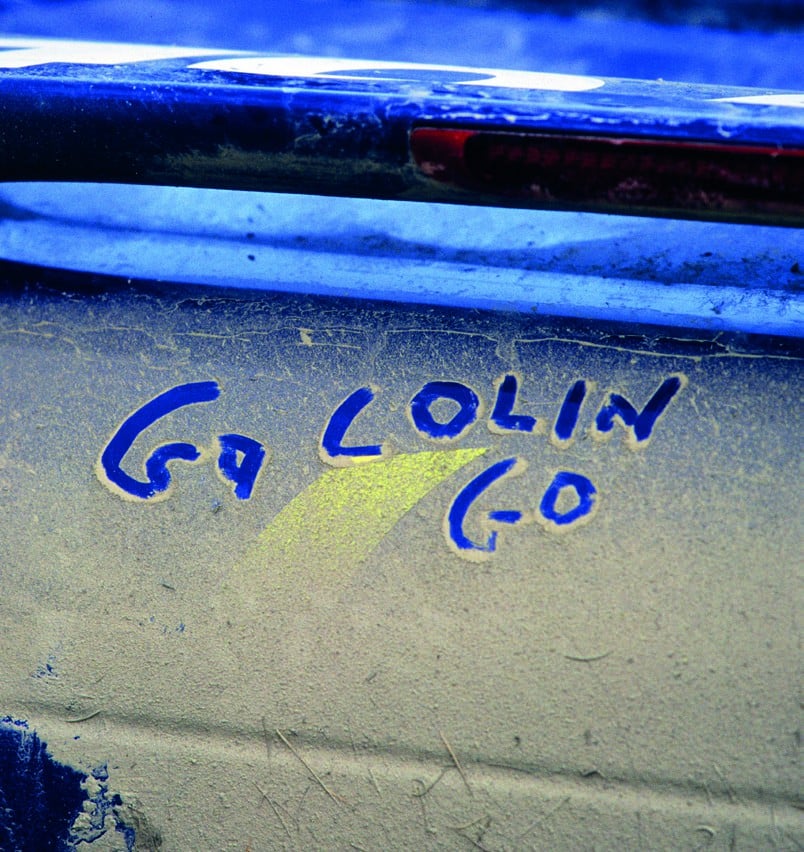

Support at the Network Q RAC Rally.

One of the best-known journalists currently on the World Rally Championship is David Evans, who has covered the series for nearly 20 years. Back in 1995 he was at university in Staffordshire, and with his dad Derek they chased around the countryside in Derek’s Vauxhall Calibra – which had been tuned by none other than Vauxhall ace Dave Metcalfe’s company – to witness McRae’s moment of glory.

Their adventure had started several weeks earlier with the arrival of the official ‘rally pack’: a folder that contained a comprehensive set of maps and instructions to help spectators plan their odyssey. Because that’s what it was back then: a high-speed tour that criss-crossed the country, whether you were competing or just watching. Of course this was before internet, rally radio, satnavs or smartphones, which made planning the whole trip and possession of a decent map indispensable.

Those without were stuck, and that’s why when a bunch of scruffy Scottish lads in a battered Peugeot asked if they could follow the Evans father and son duo, they were only too happy to help. The same arrangement persisted for the following day, and in conversation it turned out they were friends of Colin. Of course, everyone was a friend of Colin’s that year, so David and Derek didn’t take it too seriously – right up to the point where their new acquaintances trooped into Colin’s motorhome at service, stuck their heads out of the door, and indicated to David and Derek: “Are yous coming or what?”

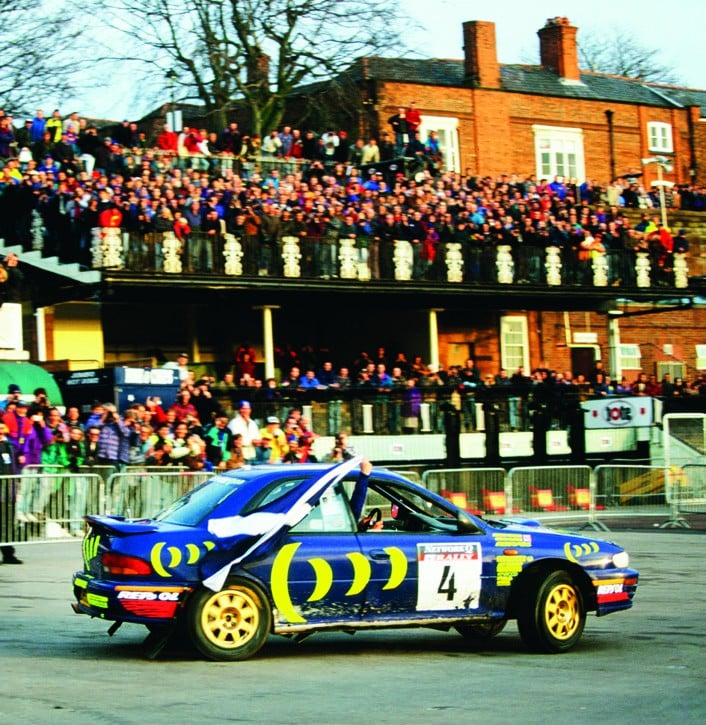

For David, who at that point was writing rally reports covering gentleman drivers for his local newspaper, it was something of an overwhelming experience. But it crowned a magical weekend, when in spite of a puncture and a myriad other little problems, Colin triumphed. “We all just knew it was going to happen; it could never be otherwise,” David remembers. “It was total self-belief.”

Sainz knew it too. “I realised quite soon that we didn’t have much of a chance. We were pushing, but no chance of a win,” says the Spaniard. “I don’t remember how I felt at the time, but now, I’m very happy that Colin won. It was good for him, for his family, and the whole sport.”

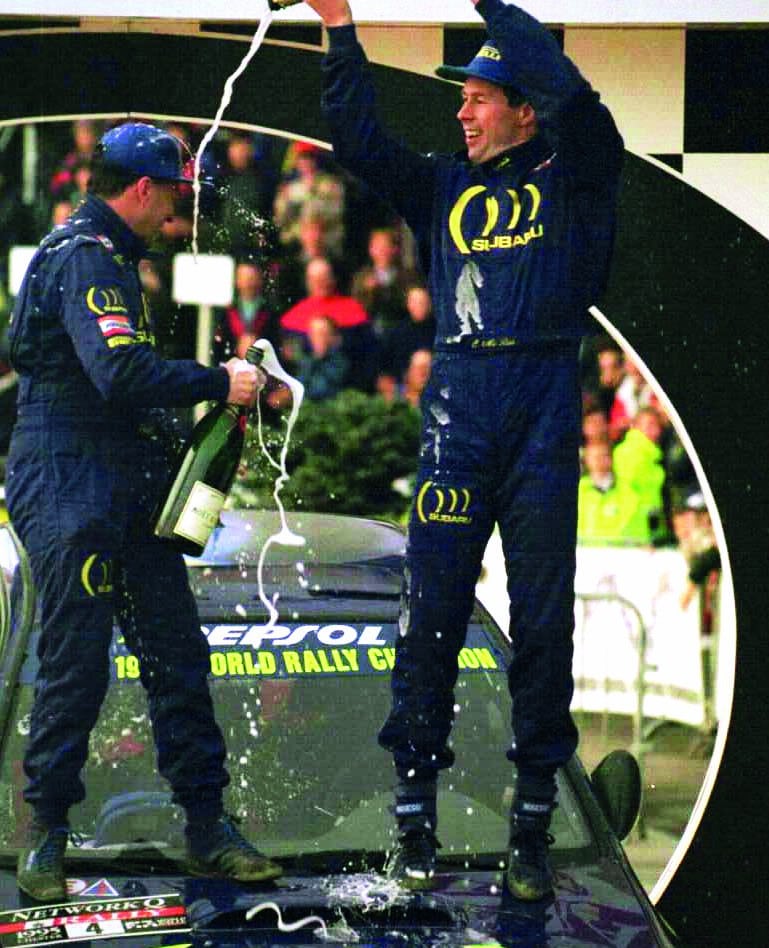

A Subaru 1-2-3 at the RAC Rally, and the first of many drinks at Chester

Shutterstock

PERHAPS THREE PEOPLE WHO HAD the best grandstand views of that historic day were Richard Burns and Robert Reid – who finished third in another factory Subaru, albeit more than six minutes behind, and Colin’s brother Alister, who was fourth in a Ford Escort Cosworth hired from Malcolm Wilson.

“At the time, we didn’t really take it in,” says Reid. “We were there with a job to do, which was to represent the team and score as many points as possible. So we probably didn’t appreciate the full scale of Colin’s achievement at the time. It’s only when you look back at it that you see how important it was. And you definitely have a different perspective when you look at it now as a piece of rally history, compared to seeing it as a competitor. But I remember that we all went out that evening in Chester and we were pleased for him – we really were – and not just because we were team-mates.”

“It was the culmination of everything we had worked towards”

Details of what went on that evening are hazy: and it’s probably best for it to remain that way. Literally, nobody can remember what happened then – nor for much of the following day.

But plenty is recorded for posterity: Alister McRae’s fourth place, for instance. “You could say that Alister was the forgotten man on that rally!” jokes Jimmy McRae. “That was an absolutely fantastic drive from him and he actually won the British championship that year, but obviously all eyes were on Colin. And that’s understandable because it was an incredible thing; the youngest-ever world champion. It took a few days for it to sink in, also because there was so much media and stuff going on for a long time afterwards.”

One of the journalists helping to create that buzz was Jerry Williams, writing for the Daily Mail. The day after McRae won the title – November 23 (a Thursday, rallies didn’t always happen at weekends back then) – the Scot occupied a good chunk of column inches in every Fleet Street paper. “It was massive news,” remembers Williams. “At the time, rallying was a sport that made proper headlines: everyone knew who Colin McRae was by the time the RAC came round. So when you look back at it, you could say that Colin’s success meant even more back then than it does now, because there’s never been anything like the same amount of attention paid to the sport since.”

But as the years go on, more photographs fall out of that mental album and the captions fade. For many people, what happened in 1995 was another era. What we see now is a completely different sport.

These days, Derek Ringer is taking life easy, in his own words, in a small village in northern Spain, having completely stayed out of the World Rally Championship since completing McRae’s last full season in 2003 (with Citroën) and returning for a couple of outings with American daredevil Travis Pastrana in 2008.

“I enjoyed the moment,” he says simply. “I think we enjoyed the moment enormously. It was a very special achievement and the culmination of everything we had been working towards. There’s no reason why Colin couldn’t have gone on and won several more championships after then, but it turned out to be just that one, which I feel privileged to have been a part of. If it had been many more championships, would it have felt more special? I really don’t think so. In the end, it’s only your body that tells you it was so long ago. The rest feels like yesterday.”