VSCC'S Senna tribute at Donington

The biggest-ever gathering of Ayrton Senna's grand prix cars will be the key feature of the VSCC's 'tribute to Ayrton Senna' race meeting at Donington Park on June 21/22. Marking…

The car was a (parting) gift to Bruno Giacomelli after a fourth season spent in Formula 1 with Ingegnere Carlo Chiti’s Autodelta SpA. That was 1982. Their agreement, however, had been struck in October 1980, a few days before the GP of the United States.

“I was in a strong position after Watkins Glen [Giacomelli had led convincingly from pole until halted by an electrical gremlin] and I signed a two-year contract,” says this ex-British Formula 3 and European Formula 2 champion. “And I insisted that they gave me a car at the end of each season. Chiti didn’t want to, to begin with, but he was a good guy and made sure that I got cars in perfect working order.”

Giacomelli took delivery of both – a 179B, chassis 03, and a 182 – on the same day: 20 December 1985. “I had to insist a lot.”

After 27 years locked in his mother’s garage, the Alfa required a seven-year restoration to get back on track

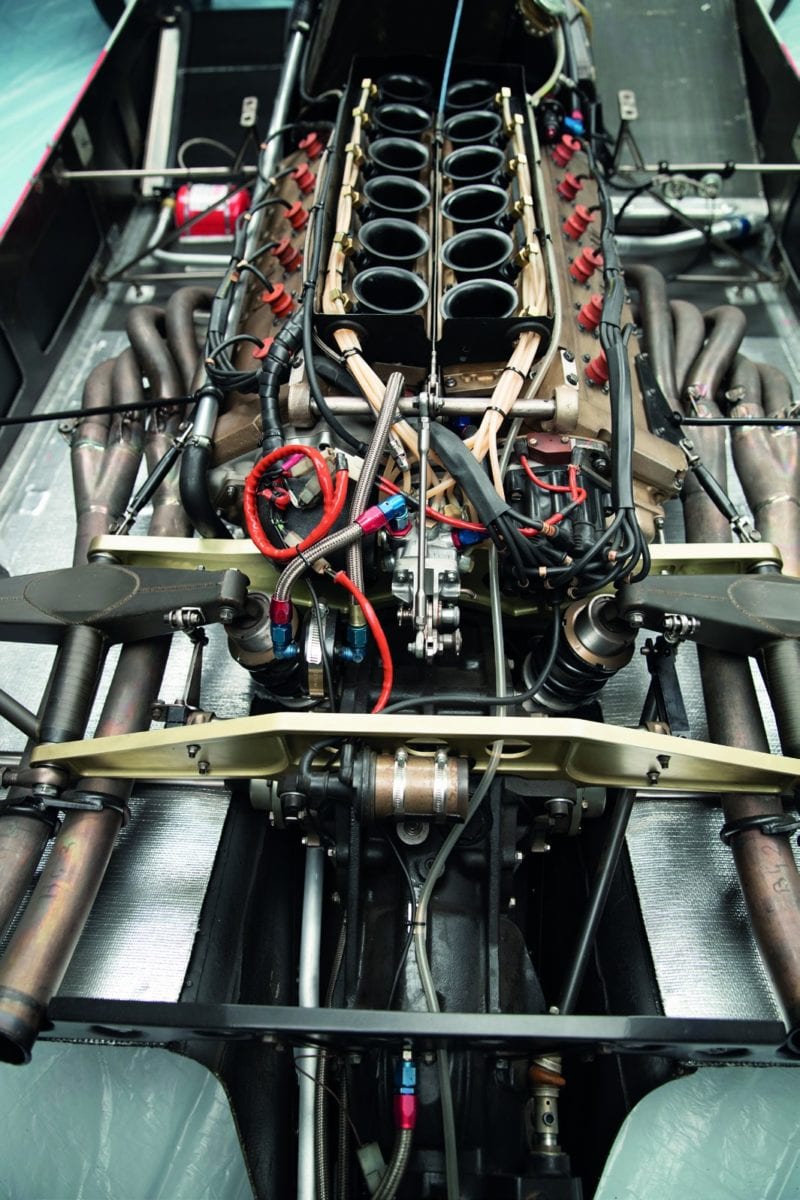

The latter was the work of ex-Ligier designer Gérard Ducarouge and featured the first all-carbon F1 tub – made by Roger Sloman’s Advanced Composites of Heanor, Derbyshire – to emerge from female moulds. Powered by Chiti’s 60-degree V12, it showed well initially, particularly on street circuits – Andrea de Cesaris was on pole and led at Long Beach and would have won in Monaco given a splash more fuel – but its performances tailed away thereafter.

“I had done all the development work,” says Giacomelli. “It was a clean car, with good power – we had 530bhp – and on the weight limit. I set a lap record for non-turbos testing on the short circuit at Paul Ricard.

“I got on very well with Andrea. He was fast, but I was more meticulous, more precise. When the team started falling in love with him, it was not really listening to me any more. And I don’t like to shout and bang my hands on the table.”

Giacomelli in the 182 at Long Beach in 1982. The car fared well on street circuits, with team-mate Andrea de Cesaris starting this race on pole – then becoming F1’s youngest pole-sitter in the process at 22 years 308 days – before brake troubles hit.

Giacomelli, let go late, would sign with Toleman for 1983, while de Cesaris remained at a restructured ‘Alfa Romeo’: the beleaguered state-owned manufacturer would farm out the design and running of its F1 cars to Paolo Pavanelli’s Euroracing for the next three seasons.

“I was busy getting on with my career and the rest of my life and I almost forgot that I owned this 182,” says Giacomelli. “My mother – she was one of my biggest fans – was its guardian. But eventually I knew it was the right time to put my hands on it again.”

The car was wheeled back into the daylight in May 2012 and transferred to long-time Autodelta engineer Renato Melchioretto, his twin sons Andrea and Daniele and daughter Manuela, the A, D and M of ADM Motorsport. Better known for its involvement in junior formulae, running the likes of future two-time Le Mans 24 Hours winner Earl Bamber, this was to be the Milanese team’s first historic restoration.

“Renato had started as an engine man at Autodelta but, when Ducarouge arrived [in 1981], he became a chassis expert, too,” says Giacomelli. “So he knew everything about this car. That was very lucky because there are no drawings, nothing; everything from Autodelta is lost.

The Carlo Chiti 60-degree V12 engine developed 530bhp in period, but had to have extensive restoration work to correct a bagful of issues, such as seized pistons and a pesky corroded water pump.

All seven years of it.

Its most onerous task was the water pump, its original magnesium casing having been ruined because someone – ahem – had forgotten to drain the coolant.

the Alfa is full of date-correct details, with Giacomelli insisting on originality.

Mario Tollentino, another Autodelta man, an early advocate of CAD and the designer/reworker of the subsequent 184T and 185T, helped greatly with this part of the project.

Giacomelli: “He didn’t have anything from those days – can you believe it? – but he had kept working in motor sport [in F1, sports cars and rallying, for AGS, BMW, Dallara, Hyundai, Lamborghini, Volkswagen] and he had a great enthusiasm for our project.

“We could have made it in aluminium but I wanted to stay with magnesium. But I didn’t want people to think that it was an original part, so I had it painted a strange colour rather than be chemically treated, which used to turn parts golden.”

Elsewhere, three pistons had seized in the bores of their wet liners. The gearbox – an Autodelta casing – was split to reveal perfect Hewland internals, complete with a brand-new crown wheel and pinion. Koni shocks were disassembled and rebuilt; this company’s former representative in Giacomelli’s hometown Brescia had not only attended the tests at Balocco back in the day but also kept his detailed notes. The Magneti Marelli distributor and the metering unit for the Lucas fuel injection underwent the same processes – the latter being the only part sent to the UK for renewal.

New gaskets, new bearings in the uprights, new pipework, new stickers, new skirts, refurbished wheels – and the car was ready for a 15-mile shakedown at a chilly Varano, near Parma, in December 2019.

Giacomelli saddles up for his first runs at Varano

Giacomelli: “People were asking if I was excited to drive it again, and I kept saying, ‘No.’ I am razionale. For me, this is normal. Remember, I was a part of the development of this car: the seating position; its steering wheel; the dash and its instruments. I had decided all these things. Yes, very many years ago, but still I knew exactly what to expect. I knew all the good work that we had done. I jumped in, started the engine, spun the wheels, went sideways a bit, and drove onto a wet track. On slicks. Normal. It ran perfectly and really I felt a sense of achievement from that.

“If you have the drawing, it’s not a problem. But we had nothing”

“I’d sold my 179B many years ago, but I kept the 182 because I felt it was an important car, even though it had never won any races. It’s pure Alfa. That doesn’t exist now. It’s just a badge and a brand today.”

But which 182 is it?

A bewildered Denis Jenkinson wrote in Motor Sport in 1982: “When you see an Alfa Romeo engineer making notes on a technical sheet about a specific car and there is no engine or chassis number on the sheet you begin to wonder if the Autodelta racing department works to any sort of system.”

Its previous aluminium chassis at least had plates glued to them – these could and would be swapped about, warns Giacomelli – but 182’s carbon item carries no identifying marks. (That’s how it left Derbyshire and how it is now.) Thus the scuffed piece of paper bearing Autodelta’s letterhead and Chiti’s signature that is in Giacomelli’s possession is priceless: it confirms his car as chassis 01. Except that even Bruno is not entirely sure if that’s right.

Giacomelli poses alongside the ADM Motorsports team. This car was ADM’s first historic race car restoration. It is more accustomed to running modern Formula 3 cars and most recently Italian F4 entries.

New stickers in place for the test.

Cue oversteer on fresh slicks

The car’s rebuild revealed professionally repaired damage to the tub’s right-front corner. Might this be the car – 02, reportedly – which De Cesaris stuck in the wall while chasing Niki Lauda’s leading McLaren at Long Beach? Sloman recalls one of the batch of five (or six) chassis – Chiti initially ordered a dozen – being returned for repair, but is unable to remember the precise date and circumstances.

Or is it the chassis which Giacomelli drove that crisp March day in the South of France, when all was new and promised so much; in which he qualified third at Monaco and briefly held second before a badly heat-treated driveshaft broke; and which pitched him into the Brands Hatch catch-fencing when its rear wing failed on the 175mph downhill approach to Hawthorns?

“It’s very difficult to see a Formula 1 car from this period that doesn’t have pieces missing or that are wrong,” he says. “That’s normal in historic racing today. My car is complete, after being stored for almost 30 years in a garage, where nobody touched it. It still has its complicated underbody wing. It has the later style of engine cover from 1982 – but it’s exactly how it left Autodelta and came to me.”

“It’s difficult to see an F1 car of this age that doesn’t have bits missing”

The pandemic stymied plans to demonstrate the car in 2020, but again razionale Giacomelli is prepared to wait. The car is stored safely – minus its coolant! – in readiness for the next right time. He might sell in the future, when provenance will be all-important – and likely quibbled over – but for now he knows exactly what he has: a genuine and moving – in both meanings – tribute to his Alfa Romeo fratelli.

“I wanted Gérard – I phoned to tell him that the car’s restoration was progressing – and Mario – he was ill, but we didn’t know – and also Andrea to see the car run again,” he says. “Sadly they have all gone now. So, too have my Autodelta mechanics.”

And Bruno’s mother Rachele, who rode Moto Guzzi in the 1950s, passed away three years ago, aged 101. Hers was a strong life that spanned the works Alfa Romeo grand prix cars of Tazio Nuvolari, Juan Fangio and her beloved son.