No rest before 2021

With the 2021 technical revolution closing in, 2020 will not be a stop-gap, says Lawrence Butcher

Getty Images

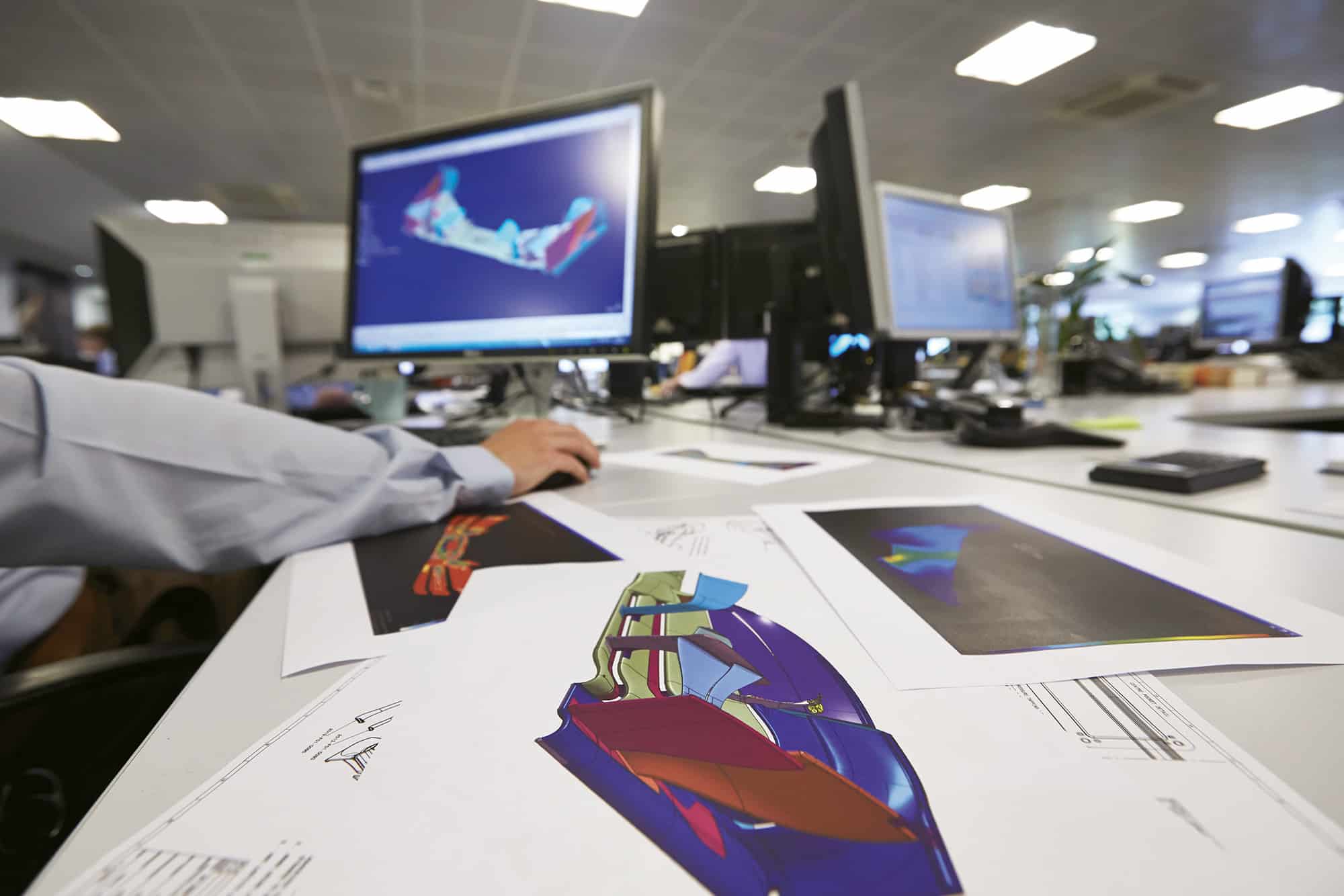

The 2020 season marks the end of an era for Formula 1, thanks to the sizeable 2021 regulation changes, but teams will not be easing off this year. Preparations for 2020 began well before last season had concluded, and the cars rolling out at Barcelona in February will be the culmination of 12 months of development, representing a carefully choreographed dance between teams’ various departments.

Even as the 2019 cars were lapping the Circuit de Barcelona-Catalunya for the first time, some teams had already started work on concepts for their 2020 machines. A few may have begun in 2018.

Most teams will have what is known as a concept group – a small cluster of engineers dedicated to looking beyond the current season and forming a blueprint for next year’s cars. The group will be tasked with picking through upcoming regulation changes, as well as any problematic areas with a team’s current car. They keep in close touch with the technical director, responsible for an outfit’s overall engineering strategy.

The early work will be broad-brush ideas, parameters to guide the later detailed designs. The complexity of the engineering work undertaken will intensify as the season progresses, steadily drawing in more resources and feeding off data gathered during the current season. The aero department will be assessing concepts and weeding out those that show little promise, while other groups will focus on the structural or mechanical design of parts. Thousands of design drawings will be generated, with ideas undergoing many iterations before completion.

There will come a point where the bulk of effort will switch to next year’s machine, depending on a team’s circumstances. If it is locked in a tight race for championship points, it may choose to push development late into the season. Conversely, if its current car is a lost cause, or if its championship position is all but assured, it may switch focus to a new challenger early.

Resource is also important – a team with 800 personnel is better able to multitask than one with just 400. But either way, McLaren’s technical director James Key says there is a balance to be struck for all teams. “You could prioritise one car over another and put a lot more focus on trying to ensure a stronger long-term future at the expense of the short term, but that’s often very difficult to do in this sport. The key is to take a pragmatic approach, balancing the cars accordingly and making sure you can get the best of all worlds.”

The dark art of carbon fibre moulding

The race to build a car

Complementing the engineering and design work is close coordination between many other departments. A vast matrix will be created that determines when each part needs to be signed off, manufactured, tested, and finally delivered to the mechanics in the build bays. Parts with a long lead time will start to be produced towards the end of the season, with the chassis and gearbox first on the list. One Mercedes team member noted: “We had parts of the chassis in the autoclaves on the day we celebrated the [2019] championship win here in Brackley.”

If an important component is late, or a safety-critical part fails crash testing, it can halt car construction. One only has to look at Williams’ tardy arrival at pre-season testing in 2019, crucially missing two days of running, to see how production delays can snowball. On the other hand, parts can be overtaken by new designs before manufacturing is finished, relegating the originals to expensive paperweights.

There is a catch for teams that rely heavily on others for major components. Haas, Alfa Romeo and AlphaTauri (formerly Toro Rosso) take the bulk of their mechanical parts – power unit, gearbox, suspension – from other teams. These parts dictate much of a car’s architecture and until they are signed off by those supplying them, customer outfits can’t finalise their designs.

Driver-in-the-loop simulators are increasingly key to F1’s technical battleground

Simulated warfare

Alongside design work, teams will be modelling and simulating every aspect of a car, trying to predict its real-world performance. They are allowed just the two pre-season tests and a ‘filming day’, where 100km of running is permitted. The only track a car will encounter before this will be virtual. Simulation is a catch-all term but,

in the context of F1, it means building mathematical models of car functions and running tests on those models, to mimic how a car will behave on track. The accuracy of these simulations, coupled to physical tests in the wind tunnel or on chassis rigs, has a significant impact on a car’s competitiveness.

Most readers will be familiar with driver-in-the-loop (DIL) simulators, pioneered by McLaren. Not just for driver training and familiarisation, these are vital engineering tools. In simple terms, the driver becomes an input in a team’s vehicle model. If a new aero concept provides amazing performance in the wind tunnel and other simulations but then makes the car too edgy for a driver to exploit, it is useless. The DIL will make this apparent before resources are wasted on physically making parts, in the same way that CFD reduces the number of parts needed for wind tunnel testing.

Up until 2019, Red Bull was widely considered to have the best DIL, but in 2020 McLaren is working to regain its position at the forefront of sim development. At the end of last year, Key explained: “Our new driver-in-the-loop simulator is a massive departure from what we’ve been using. [McLaren’s existing sim is] still extremely effective and doing its job, but the technology has moved on… It’s a completely fresh start.”

Alfa Romeo has also finally joined the DIL simulator game, with the team installing one at its Hinwil base for the first time and filling an important hole in its engineering armoury. This will no doubt complement the outfit’s expansion – ongoing since 2017 – to better capitalise on developments from its aero team and other departments.

Butcher’s close-up snaps show the Ferrari/Mercedes contrast

Will Mercedes follow a Ferrari design trend?

The 2020 season represents relative stability from a regulation perspective. With no major changes, it is fair to assume that most teams’ cars will be evolutions of their season-ending designs. Some trick details will become apparent once the cars are seen in the flesh, but there will also be a continuation of trends from 2019. Font wing designs will most likely continue to converge, and teams were out testing 2020 development wings during the closing races of last year.

At the start of the season, there were two clear camps when it came to front wing concepts: that taken by the likes of Ferrari and Alfa Romeo, and at the opposite end, Mercedes. The latter, according to Mercedes technical director James Allison, was a result of the Silver Arrows’ long-running philosophy of generating a lot of downforce at the outer ends of the wing, hence the full-height profile of the wing elements outboard. The disadvantage of this design is that it is difficult to generate outwash, a problem Mercedes managed to mitigate.

Ferrari and Alfa’s tactic was very different, with their wing designs sharply sloping towards the endplate, forcing air outboard and the inner portion of the wing making the majority of downforce. This gave them greater control over the outwash, but with a potential loss of outright downforce. By the end of 2019, it seemed the Italian approach was finding greater favour, so 2020 should bring a further move in this direction. Whether Mercedes dumps its long-standing approach remains to be seen.

Winds of change: Mercedes’ wind tunnel in action

There were, however, some tantalising glimpses of Mercedes’ potential development direction. A pre-season video of Valtteri Bottas’s seat fitting showed the chassis mock-up, which looked quite different to that seen in 2019. It appeared the team was moving to a different sidepod layout, with the upper side-impact structure sitting lower on the 2020 tub than in 2019, which could indicate a move to Ferrari-style air management.

Power output will continue to converge. Ferrari arguably retained the upper hand at the end of 2019, but gone are the days where the field was separated by three-figure power differentials. Someone may find a step, as Ferrari did in 2019, but such gains are harder to come by now the power unit technology is mature. Honda and Renault are hot on the heels of Mercedes and Ferrari and a key performance differentiator will now be the efficiency of generating downforce.

Then there is the matter of tyres. Pirelli’s 2019 rubber caused no small number of complaints across the field, Haas being a clear example of the troubles that befall those who can’t get the tyres into their operating window consistently. But despite the option of new compounds for 2020, teams have been refining their tyre models through the season and voted to stick with the existing formulations.

The tight midfield battle

It is unlikely that anyone will gatecrash the top three in 2020. But if Honda continues its rapid development with Red Bull, and Ferrari gets on top of its organisational and strategic issues, the fight at the front could be a tight one. But how the midfield battle shakes out is anyone’s guess. A fraction of a percent in performance can mean the difference between fifth and 15th.

Racing Point was in administration at the exact time it should have been finalising its 2019 car design, right before the outfit was saved by Lawrence Stroll’s consortium. The new investment came too late to remedy the immediate deficit. As a result, the 2019 car was, according to technical director Andy Green, just an update of the 2018 VJM1, meaning 2020 will be “the first true Racing Point car.”

Extra staff have been brought in, a new factory is being built and, significantly, Racing Point’s wind tunnel testing has switched from the Toyota facility in Cologne to Mercedes in Brackley. Racing Point also completed a major update to its CFD cluster.

McLaren’s fightback continues as changes to the engineering department, spearheaded by team principal Andreas Seidl and Key, start to pay off. As well as the simulator upgrade, there’s a new wind tunnel on the way and pitstop equipment. Notable is the rearrangement of the team away from the matrix management structure of Ron Dennis, the consensus being that this led to inertia with no one individual taking responsibility for the engineering direction.

There will be many interesting plotlines elsewhere in 2020. Can Williams pull itself out of its downward spiral? Former engineers from the team hint that Williams has been unwilling to change some of its ingrained methods, but now Patrick Head has returned to the team and Claire Williams has spoken of a “new culture” in 2019. But it remains to be seen, with no clear engineering leadership, whether the team can rebuild.

Renault has a point to prove, not least to its board. It has had huge investment in facilities, and for 2020 the engineering management has undergone a shake-up. Long-time technical director Nick Chester and aero specialist Peter Machin have left, replaced by the returning Dirk de Beer. Ex-McLaren man Pat Fry has also joined. But the new signings will have had little chance to influence the 2020 car. Renault’s target should be regular podiums, but the manufacturer still has a mountain to climb (a 1.4-second average deficit in qualifying to Mercedes in 2019), and it cannot afford to be trumped by its engine customer McLaren two years in a row.

Meanwhile, the spectre of 2021 will loom large over teams. Massive change is coming, and most will already be hard at work on their car concepts. Any outfit switching focus too late, choosing the short-term gain of 2020 championship points, could well spend the next half-decade playing catch-up.

Hanoi has corners inspired by F1’s most famous circuits

F1’s new street race

As Hanoi edges closer to being ready as a host venue, Stewart Bell visits the new Vietnam Grand Prix circuit

Vietnam may not be known for its motor racing pedigree, but it is set to become key to F1’s plans to launch into Asia. When the country’s first grand prix around the streets of Hanoi happens in April, it is hoped it will act as a springboard to a new market.

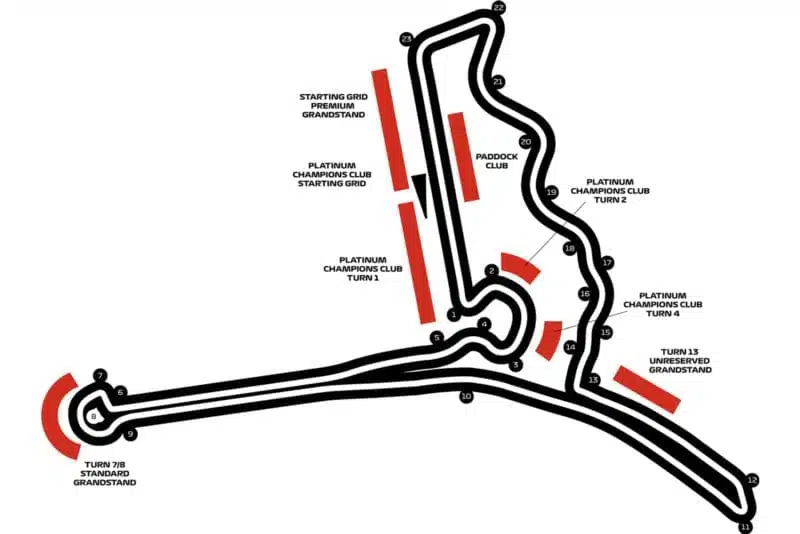

The first impression is that the new circuit layout is nothing if not bold. It opens with a Nürburgring arena-style complex, and then has two parallel straight sections linked by a sweeping 1.5-kilometre back straight, and a challenging final sector with corners reminiscent of Monaco, Suzuka, and Sepang. The 5.607km lap’s top speed trap is expected to clock in at 335kph (208mph).

To the purists, the layout might look audacious, but it’s been designed for better racing after much closer collaboration between circuit designer Tilke Engineers & Architects and F1’s motor sport division.

“I think that this is the first time they have worked so closely with each other to develop such a track,” says Vietnam Grand Prix Corporation CEO Ms Chi Le Ngoc, exclusively to Motor Sport at the promoter’s Hanoi office.

“I understand Ross Brawn has followed the development and design of our track very closely. I mean, who’s better than Ross Brawn to do this job? He knows what makes a track exciting, and for all the drivers to showcase their skills.”

The Vietnam GP street circuit, like the Australian and Singapore grands prix, has both permanent and temporary sections – with the pit straight, pit building and the final sector from Turns 12-22 remaining after the event. The opening arena complex and parallel straights from Turns 5-12 uses existing arterial road Le Quang Dao, along which are both shopping centres and commercial buildings.

The majority of the track, including Turns 10-12, is actually in the Phu Do district, which encompasses the 40,000-seater My Dinh National Stadium that the track pivots around.

“If we bring F1 to Vietnam it will be the biggest chance for us to showcase Hanoi and Vietnam to the world,” Ms Chi says. “And last but not least, we want the Vietnamese people to have a chance to attend something so big, on a scale that Formula 1 grands prix offer.”