Kenny Acheson, back behind the wheel of 'lovely' Sauber-Mercedes C9

Team driver Kenny Acheson recently tuned back in to his Silver Arrows Sauber Mercedes C9. Gary Watkins was there to see an unlikely reunion

Kenny Acheson hadn't driven a race car in anger since retiring almost 25 years ago, before being reunited with the C9

Lyndon McNeil

The overalls still fit and so, by definition, does the cockpit. Thirty years on from the most successful season of his racing career, Kenny Acheson is easing back behind the wheel of a Sauber-Mercedes C9 in the same grey Nomex in which he won two rounds of the 1989 World Sports Car Championship and endured a heart-breaking near-miss at the Le Mans 24 Hours.

Acheson, now 62, feels immediately at home in the Silver Arrow that put Mercedes back on the international motor sport map in only year two of its official comeback. He’s not driving the car on a circuit – he hasn’t had a competition licence since he walked away from the sport nearly a quarter of a century ago – but on the Turweston aerodrome runway just down the road from Silverstone. But it’s enough to rekindle some fond memories.

“The strangest thing is that it doesn’t feel strange at all, if that doesn’t sound a bit odd,” says Acheson, who has driven a racing car just the once, and only for a short demo, since retiring in 1996. “It all felt so natural – the noise of that V8 engine brings it all back. It really is a lovely racing car.”

But then the Northern Irishman knew the C9 was something special from the moment he first took to the track for what should have been his race debut with the renamed Team Sauber Mercedes squad at Le Mans in 1988.

Acheson took the car to second at Le Mans in 1989

Alamy

He had reservations about going back after a fraught maiden appearance at the Circuit de la Sarthe in 1985, which ended before qualifying was over with one of his team-mates in hospital with a broken leg.

“A Porsche 962C was scary, but the C9 was an entirely different proposition”

He describes the Porsche 962C in which he completed just three laps as “awful and a bit scary – for some reason I couldn’t go flat in a straight line”. Three years later, the C9 was “an entirely different proposition — you could tell immediately that it was a good racing car”.

Accepting the offer of a Le Mans drive with the Swiss Sauber team turned out to be a pivotal moment in Acheson’s career. He might not have got to make his Le Mans debut, but his introduction to the factory Merc squad resulted in a full-season campaign in the following year’s WSCC, or World Sports-Prototype Championship to use the name it adopted in 1986. Top drives followed as he racked up an impressive Le Mans CV that encompassed a trio of podiums in his first four starts.

Acheson was given a second outing aboard a C9 at the back end of the ’88 season at Fuji, a home from home for him after four seasons racing in Japan. He finished fifth with Jean-Louis Schlesser and Jochen Mass, doing more than enough to be invited back for ’89.

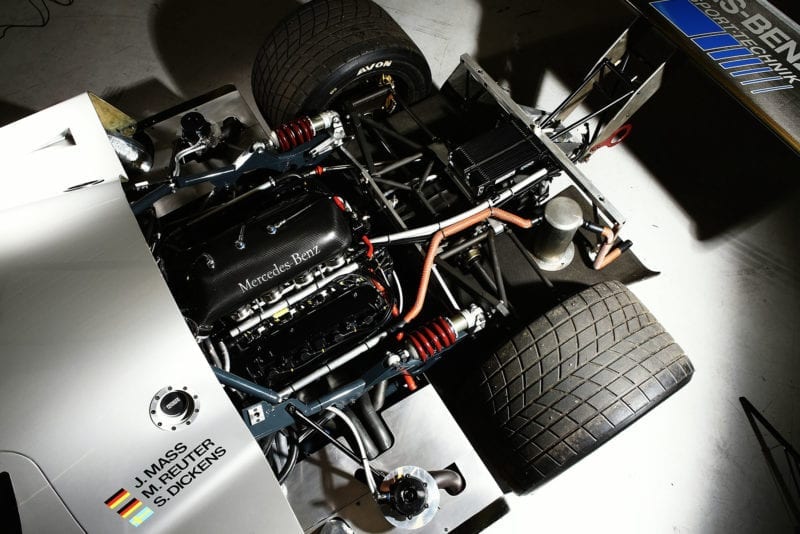

Twin-turbo V8 engine is the heart of the C9

Lyndon McNeil

“I went there as a fifth driver, but every time I got in the car it was wet and I was quick,” he recalls. “I remember the team telling me I was going to start the race. I said to them, ‘hang on a minute, I’m not one of your regular drivers, I’ve only done a handful of laps’.”

Acheson would be part of an historic year for Mercedes as both the manufacturer and its Swiss partner upped the ante. Sauber outgunned its rivals, including reigning champion Jaguar, which meant the big rivalry was within the Swiss team.

Schlesser and Mauro Baldi had started the 1988 season as co-drivers, winning first time out at Jerez and finishing on the podium at the next two races before the team expanded to run a pair of cars. Now they would be in separate entries from the outset, Baldi teamed with Acheson in car #61 and Schlesser lining up with Mass in #62.

“They were the two bulls in the field,” recalls Acheson. “Jochen was really relaxed as always and I was just happy to be there. I was always aware of the rivalry, but I don’t think it ever got in the way of things.”

Schlesser wasn’t happy from the get-go that Dave Price had been assigned to engineer the sister car, even less so when Baldi, recovering from breaking his right foot at the Daytona 24 Hours in February, ended up driving – and winning – with him at the season-opening Suzuka round. The team was forced to shuffle its line-up on race morning when Mass fell unwell. With the team down a driver, that meant Acheson had to race #62 alone over a 480km or 300-mile event lasting nearly three hours.

“Acheson had to race alone for a 300-mile, nearly three-hour, event”

He ended up second, six seconds in arrears of the sister Sauber, but the newcomer was the moral winner after ceding his position to the car shared by the two bulls late in the race.

A run in the Sauber brought back plenty of memories for Acheson

Lyndon McNeil

“I started 30th because I had to use Jochen’s qualifying time,” he remembers. “I thought there was no way I was going to be able to do the whole race on my own, because these are physical cars and Suzuka is a tough circuit. But suddenly I found myself running second and I was able to overtake Schless in the last stint.

“He claimed he believed I was unlapping myself. He didn’t! I caught him and pulled away by a couple of seconds before the call came. When I pulled over, I made sure I did it in front of the pits to let everyone know what was going on.

It is believed body panels came from the Le Mans-winning car

Lyndon McNeil

“I sat on his tail to the end of the race, and it was only on the last lap when he nipped in front of someone in the S-Curves that he was able to pull a gap.”

Neither Baldi nor Schlesser took the big prize at Le Mans that year. Instead it went to Mass, who was teamed with Stanley Dickens and Manuel Reuter in the additional #63 car entered for the French enduro. It might have been different, however.

Baldi, Acheson and third driver Gianfranco Brancatelli held the lead on Sunday morning when its number one driver went off at the Dunlop Chicane. This incident and subsequent repairs to a damaged nose turned a narrow lead over the sister car into a one-lap deficit.

Acheson had plenty of success during the 1989 season, here celebrating winning the 1000km of Brands Hatch alongside Mauro Baldi (left)

Getty

The second-placed Sauber made it back on to the lead lap, only for the gearbox to jam in fifth on Acheson’s first lap back in the car for the run to the flag. When attempts to repair the transmission proved fruitless, the car’s driver had the big task of getting out of the pits in top gear.

“All I did was keep hitting the starter and dropping the clutch, so the car would keep rolling,” he explains. “Start, drop the clutch and stall; start, drop the clutch and stall. By the end of the pitlane, the clutch seemed to be burnt out and I couldn’t really accelerate. I remember getting onto the Mulsanne and two thirds of the way down the clutch started to come back as it cooled down a bit.”

Another WSPC win for Baldi and Acheson at Spa in September, coupled with a retirement for Schlesser and Mass, meant the Italian went to the series finale in Mexico City with a narrow advantage at the head of the championship table. But on the assumption of a Sauber one-two, he still had to win the race to claim the crown.

Baldi took the pole, but it was Schlesser who led throughout the opening stint on the Autódromo Hermanos Rodríguez. Acheson, though, quickly closed down Mass after the pitstops and outdragged the sister car on the start-finish straight after getting a better run out of the fast 180-degree Peraltada.

“You were in trouble if you got it sideways when the tyres were old”

Just a couple of laps later, the Sauber driver attempted the same move on the lapped Richard Lloyd Racing Porsche driven by Tiff Needell. This time, the C9 ended up in the barriers. “I had Jochen just behind me and I knew I had to get a good run onto the straight,” recalls Acheson. “I didn’t want to get too close to Tiff in the corner, but I came up right behind him and lost downforce in his slipstream just at the point where there was a bump in the road.

“The Michelins were very difficult to drive: you were in trouble if you got the car sideways once the tyres were five or six laps old. The car went ever so slowly, but there was no chance to get it back on those tyres. I was just too close to the car in front at the wrong moment. My fault. Maybe it wasn’t meant to be.”

Acheson already knew that his services weren’t required for 1990 by the time he headed for Mexico. His seat would be filled by a trio of youngsters – Michael Schumacher, Heinz-Harald Frentzen and Karl Wendlinger – as Mercedes motor sport boss Jochen Neerpasch sought to replicate the successes he’d enjoyed with his junior programme at BMW in the 1970s. The young tyros would alternate in the second car alongside Mass, while Schlesser and Baldi were reunited in the lead entry.

Acheson wouldn’t drive a Sauber again after climbing from his damaged car in Mexico. Not, that is, until the offer last year to reacquaint himself, however briefly, with the C9. The run, however short, enables him to look back on his time with Team Sauber Mercedes with fondness.

“I feel lucky that I got that chance with Sauber and Mercedes,” he says. “If I hadn’t have got that opportunity, I’d probably have done a couple more years in Japan, and that would have been it. My life wouldn’t have been so rich.”

His exploits in 1989 won him the British Racing Drivers’ Club Gold Star for the most successful Commonwealth driver of the season. He calls himself the “least famous and least-deserving name” on an honours board that includes Richard Seaman, Stirling Moss and every British Formula 1 world champion. That’s a typically self-deprecating comment from a driver who was always one of the nice guys of the paddock.

Despite a 30-year gap since he raced it, the cockpit of the C9 was familiar to Acheson

Lyndon McNeil

“I couldn’t speak highly enough of the group of people I raced with in 1989,” continues Acheson. “It was the nicest atmosphere I ever encountered in a team. Everyone worked well together, the Germans, the Swiss and the Brits.”

The chance to once again slip into the cockpit of a C9 results in “a great day” for Acheson. “The only thing is,” he says, “it’s the wrong number on the car. If there was no #63, I would have won Le Mans.”

Special thanks to BBM Sport for its help with this feature

SAUBER-MERCEDES C9

Chassis: aluminium honeycomb

Suspension: Double wishbones all round

Engine: Five-litre Mercedes M119 90-degree V8, twin turbos, four valves per cylinder

Power: 700bhp-plus

Torque: 600ft lb

Gearbox: Five-speed Hewland VGC

Weight: 900kg

A lunchtime coincidence

This Sauber’s owner had no idea he was sitting across from Kenny Acheson during an encounter at Goodwood, which led to this test

Kenny Acheson’s return to the cockpit of a Sauber-Mercedes came about entirely by chance. Invited to a corporate event at the Goodwood Festival of Speed last summer in his capacity as a businessman working in the cosmetics industry rather than as an ex-racing driver, he happened to sit opposite the owner of this C9, historic racer Rupert Clevely.

“Kenny asked me what I did and I ended up telling him that I raced a bit,” explains Clevely, who has also owned Lancia LC2 and Peugeot 905 Group C cars. “He asked me what car I drove, I said it was a Sauber. When I told him it was a C9, he said, ‘Wow, I finished second at Le Mans in one of those’. I had no idea who he was when we started talking.”

One thing led to another, and suddenly Acheson was digging out his old overalls for a short test in Clevely’s C9.

The car was purchased from the defunct Donington Collection by Clevely. An unraced spare car in period, chassis #89 C9 A1 became a display vehicle at the end of the design’s competitive life early in 1990. The car came with an engine and gearbox, but no bellhousing between them, while other missing parts included the injection plenum and the rear suspension rockers.

What the car did come with, however, was a set of bodywork used at Le Mans. It is believed that the majority of the panels came off the Le Mans winner, while the 04B chalked inside the nose suggests that this section was used on Acheson’s second-placed car, chassis #04.

BBM Sport, formerly Chamberlain-Synergy, readied it for Peter Auto’s Group C Racing series. That meant reverse engineering components, something it was well qualified to do having previously run another C9, as well as the Sauber-built Mercedes C11.

The car was ready in time to run up the hill at Goodwood last summer and the plan is for Clevely to race the C9 a couple of times in the coming season. “I’m a massive Group C fan,” he says, “and in my opinion this is the coolest looking of them all.”