Rodin's FZED is the closest you’ll get to F1

Only a select band of people know what it feels like to drive a Formula 1 car. But for the (mere) price of a hypercar you too can now experience those staggering g-forces. Andrew Frankel flew across the world to explore new limits

I’ve been trying to think of a way that explains even adequately what we have here. I could tell you it’s called the Rodin FZED, I might mention that it is a highly developed version of the failed Lotus T125 project. I could even tell you it’s the closest thing to a reasonably modern Formula 1 car most merely wealthy rather than impossibly rich people might imagine being able to buy and run.

Born from a Lotus project, Rodin’s FZED has been re-engineered for driveability and even greater performance

But that doesn’t really do it. So let me put it another way. Let us imagine you’re a decent driver, with some talent and experience driving quite fast racing cars, be they historics, or modern GTs. I reckon if you were just planted in this car and sent out on a private track, at best you’d learn nothing other than experiencing a new world record from going from zero to absolutely bloody terrified. At worst, well, let’s not even think about that.

“It will be called FZERO – because what’s one better than F1?”

I’ve been testing and driving racing cars for half my life and I still needed a full day of hands-on education before my tutor felt I was ready even to drive it. It would be another day before I got to go flat out. And he was right. But before all that, I had to travel to meet it, not at Silverstone or Donington, but the other side of the world: New Zealand, no less.

The company behind this car is called Rodin, after the sculptor, and particularly his most famous work, The Thinker. And it speaks volumes about its founder David Dicker, a man who thinks a very great deal, all of the time.

Australian by birth, he decamped to New Zealand describing his homeland as “the most over-regulated place on earth”. He loves New Zealand where, within reason, you can do what you like. Which in his case involves running unsilenced racing cars around his private race track. Or three private tracks if I describe accurately his extraordinary facilities in the north east of the South Island. One is the original track, one looks like a rollercoaster ride in race track form that I’m going nowhere near, and the third is a perfectly sensible 1.5-mile circuit with a good blend of fast- and medium-speed corners and a pleasingly long not-quite straight.

For a start-up firm Rodin’s facilities are impressive

Up until that moment, I’d been tempted to think of the Rodin project as one of those nice ideas that occur to men of a certain age with a certain amount of disposable income, almost all of which never come to fruition.

But then I saw the tracks, the facilities, the machines, the staff and the cars and started to wonder if I’d not rather underestimated David Dicker. Then I was told about the $1.6 billion his company, Dicker Data, turned over last year; then I heard from the man himself.

On one of Dicker’s three tracks, the FZED displays adhesion and braking far beyond most people’s experience

David Dicker is self-made, a man who got bored in his father’s air-con business and discovered he’d rather sail boats and race cars. He’s 66 now, but quick enough to win the Am category of the Ferrari Asia Pacific Challenge series in 2018. He’s reticent at first but start talking cars in general or F1 in particular and he warms up fast. What interests me is not his vast car collection or his split existence between NZ and Dubai. It’s that unlike most wealthy people who have got that way through graft, risk-taking and exceptional business sense, Dicker is happy to talk about the mistakes he’s made. He is astonishingly self-aware and it’s that, more than his wealth, that makes me think his plan will work.

“I started late because I needed to be in a position to do what I wanted to do,”he says. “So many guys start these projects thinking they can do it for ‘x’, then find they need ‘2x’, which they don’t have. So they then either do things that hurt the business or, more often, they’re screwed. History is full of them.”

So now you may be surprised to learn that “what I wanted to do” was not the Rodin FZED quasi-F1 car I am nervously eyeing up in the garage. “It was never part of the plan, but one day I got an e-mail from Lotus wondering if I was interested in a car they’d made. I took a look at it and thought ‘that might help’.”

The car in question was the T125, one of many stillborn Lotus projects of the Dany Bahar era. You may remember it – Clarkson drove it on Top Gear when it was new in 2011. The idea was to create a car that delivered as close to a genuine F1 experience as possible, but which mere mortals could afford both to buy and run. A good idea but little came of it.

Rodin’s ‘Thinker’ badge; below, printed steering wheel; left, Cosworth GPV8 based on Indy unit

“I think in the end they sold five cars before contacting me,” says David. He was interested because his grand plan was – and remains – far more ambitious than even the T125. He calls it FZERO, not because of its emissions – it’s going to be powered by a 1000bhp twin-turbo petrol engine – but because it’s designed with zero restrictions and because, as Dicker puts it, “what’s one better than F1?”

“Earlier I wanted to run away from this car. Now I want to get going”

And it’s FZERO that shows the full scope of Dicker’s ambitions: a closed-cockpit car powered by a unique 4-litre V10 engine of Dicker’s design that’s being engineered for him by Neil Brown Engineering in Lincolnshire. Ricardo is creating an eight-speed gearbox for the car, again to Dicker’s design.

There will be a normally aspirated version with a piffling 700bhp, while the turbo will start at 1000bhp but could go much further. There is talk of F1-busting lap times, 0-186mph in 10sec, many tonnes of downforce, a road-legal version and a price tag of $1m, which in Aston Martin Valkyrie and Mercedes-AMG One terms isn’t that much. Indeed I don’t think Dicker wants to make a killing on the FZERO, I think he just wants to show the world he can do it. And having spent three days with the man, I wouldn’t bet against it.

But now attention returns to the FZED. And more lacerating honesty. “If I’d known what I was taking on, I probably wouldn’t have got involved. It seemed like a good way to accelerate our knowledge base as we worked towards the FZERO. But the truth is if we’d not done the FZED, the FZERO would already be running.” As it is we’ll have to wait until later this year to see the finished product.

Slicks, wings and 675bhp – and you don’t have to wait until raceday to drive it…

Dicker’s particular problem with the Lotus was that it was horrible to drive. “You could barely get it out of the garage. Watching him stall it repeatedly on television was probably the only time I’ve felt sorry for Clarkson…”

So he went to work and two years later ended up with a car that looks similar to the T125, but is transformed underneath.

The first job was to lighten it, and because Rodin has some of the most sophisticated 3D printers in the world, it was able to carve 41kg from the 650kg T125. Everything from the steering wheel and seat to every individual fastening is now made from printed titanium.

The engine is a Cosworth GPV8, based on the XG IndyCar motor. It displaces 3.8 litres and had 640bhp at 11,000rpm in the Lotus. Now with a Rodin titanium exhaust it has 675bhp at 9800rpm; divided by 609kg of mass that’s a power to weight ratio of 1067bhp per tonne, double that of a Bugatti Veyron. That’s why it takes a lot of learning.

Rodin has an answer for that too, in the unflappable form of Mark Williamson, a 55-year-old Australian racing driver who’s competed in everything from serious single-seaters to the GT4 cars in which he is still super-competitive today. His job is to get me match-fit for the FZED.

So we start in a GT4 McLaren 570S race car, which is one hell of a trainer. I’m using it to learn the track more than anything, but it’s a fabulous weapon: fast, forgiving, monstrous on the brakes and pretty snappy down the straights, too. Mark sits next to me, shows me which way to go and tries not to wince.

The next step is a Dallara Formula 3 car. This is essential for understanding how a ultra-lightweight single-seater with significant downforce behaves. I’ve track-tested single-seaters, but this is different: I need to do more than just get a feel for the car, I must drive it as fast as I can.

It’s not that nice. Its hand clutch is evil, the engine only works at full throttle, the steering is hideously heavy and I can’t get my head around its brakes. And they’re conventional steel discs. How will I cope with the full carbon/carbon set up on the FZED?

Carbon-fibre suspension arms operate inboard coilover shocks

I was getting it all wrong. I knew I wasn’t near the limit and I didn’t have Mark next to me. He was meant to be talking over the radio but my brain was so focused elsewhere it could not discern a word.

But it’s amazing what a bit of time out of the car in the company of Mark, the data, the onboard camera and a packet of chocolate biscuits can do. And in my next stint I just trusted it would stop from where Mark said it would stop and go flat through corners that looked like they needed brakes and a downshift.

Then I began to understand. Just a little. Downforce like that is addictive and I can now see why drivers love it. It’s not just the extra grip, it’s the way it makes the car feel planted in a way that four patches of wobbly rubber never could.

So that was the tuition. But before I could drive the FZED, I needed a fitting. Initially I thought making a bespoke seat insert (where you sit effectively in a bean bag and mould its contours to your shape before resin is poured in and allowed to set) was just a bit of theatre. Now I know that without it you’d be so black and blue you’d feel like you’d been mugged.

I was told I’d find the ultra-reclined, knees-up driving position strange, but to me it feels natural. I was more worried about left-foot braking which, save the odd kart when I was a kid, is something I’ve never done. “You’ll be amazed,” says Mark. “You’ll think about it the first time and not again. It’s not even an issue.” We’ll see about that.

“You can be the fastest person at any track day anywhere in the world”

More concerning to Mark are the brakes themselves. “One of the great things about carbon/ceramic brakes is they don’t need much heat to start working. They work better when hot, but they won’t stick you in the wall on your out-lap. Carbon/carbon brakes will. Unless they are hot, you have no brakes.’ He’s so concerned that when we need to do 40mph tracking shots behind a camera car, he insists on driving. “It would be so easy to drive into the camera car. I’ll use your helmet and no-one will notice…”

Finally it’s time for me to drive and though I can’t quite explain this, a strange calm descends on the cockpit. Thanks to the team’s efforts I’ve never been more comfortable in a racing car. I know the track, I’ve done competitive times in the F3 car and the weather is good. Just 24 hours earlier I wanted to run away from this car; now I just want to get going. That’s how good the training is.

The titanium steering wheel holds all the controls I’ll need, and I won’t need many of those. Someone plugs in the external starter, I catch the engine on the throttle and 3.8 litres of very angry Cosworth blasts into life. It reminds me of a DFV in an unusually bad mood. The enormous Avons have been in warmers for hours and are nicely cooked, so let’s not waste time letting them go cold.

In so many ways the FZED is far easier to drive than the Dallara, at least until you try to go fast. On this initial, exploratory outing all I have to do is learn about the brakes and go sufficiently rapidly for the tyres not to fall off the end of the grip cliff. Initial observations are that the hand clutch is more progressive than the Dallara’s, vibration levels are so reduced the FZED feels like an S-class, the steering is much lighter and if I want to use part throttle, it doesn’t want to pogo down the track. It’s all very reassuring.

Apart from the brakes. You stand on the pedal and nothing happens, which is quite disconcerting, and then the brakes come in so hard and fast your brain associates the deceleration with an impact. Which is more disconcerting still. I do a few laps using around 8000rpm – then head for the pits, smoothly using the clutch pedal to bring it to a halt, until I remember it doesn’t have a clutch pedal and that’s actually the brake I’m pressing which is why the car stalls 100 yards shy of the pit garage. Professional it is not.

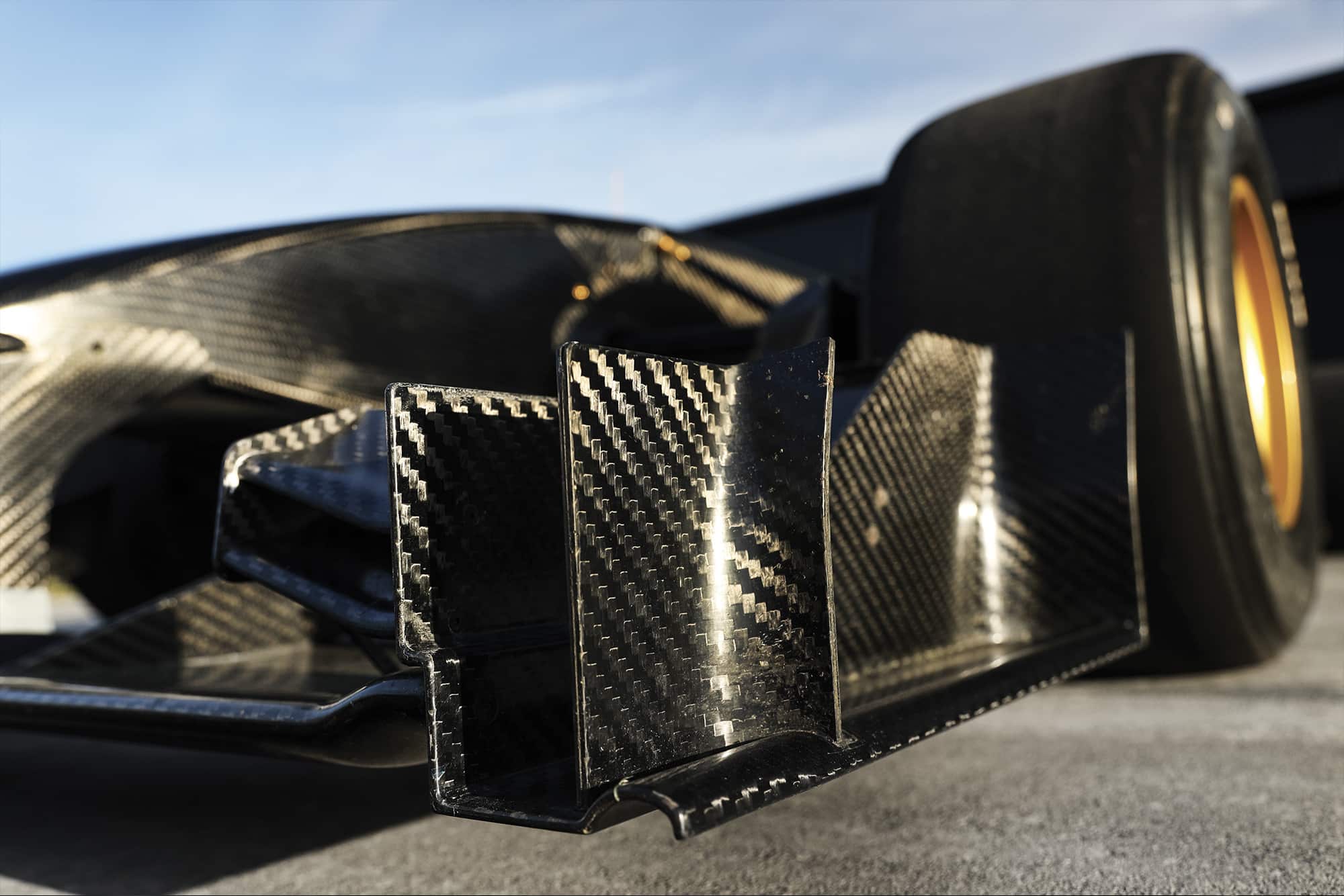

Rear venturis confirm that downforce is central to the Rodin experience

In some regards driving this car feels like walking into a super-luxurious hotel room in a land far, far away: extremely welcoming, exceptionally comfortable, full of interesting stuff, yet still utterly unfamiliar.

More data, more biscuits. Mark says I’ve done really well; I suspect his public relations skills may be as great as his driving talent.

The following morning there are no more rev-limits. And like so many racing cars I’ve driven, once you drive it the way it’s designed to be driven, suddenly it makes sense.

Of course the acceleration is shattering. A 0-100mph time of 5sec does no justice to it because traction limitations mean it would be on part throttle for most of the run. But you can get used to that. At the exit of slow corners where traction needs are highest and downforce is lowest you need to be careful about where you jump back on the throttle, but if you’re progressive, or just wait until the car is straight, there’s not much to fear here.

Corners are more difficult, especially if you have a background in historic racing. The apex speeds will make you laugh or gasp depending on whether the corner is slow or fast: once the downforce kicks in adhesion levels are far beyond anything I’ve known. But my insistence on playing with the throttle mid corner is in danger of landing me in trouble. Where I come from it’s just what you do: pitch it in and sort it out. But in a car like this, constant minute pitch changes can play havoc with the downforce generated by the floor of the car, which is most of it.

Carbon fibre, centre-lock wheels and a Cosworth V8 – Rodin works to F1 spec levels

But even that I learned. Brake all the way in, smoothly accelerate all the way out. Not having to move a foot from one pedal to another really helps. Soon I was even able to make it oversteer on exit without scaring myself senseless. The car is now so well set up even the reactions of a bloke in his mid-50s who’s never driven anything like it before are enough to keep it pointing the right way.

The brakes, however, I never got near. I was pleased to have come close to Mark’s times in the F3 car, but in the FZED I remained a mile away. I blame my left foot. At the end of the straight I was braking at 150 metres from around 175mph, which felt pretty damn brave to me. Mark brakes at 80 metres, which is beyond not just my ability, but my powers of imagination. The subconscious part of your mind looks at what the conscious part is trying to do, concludes it’s gone mad and takes over.

I came away from Rodin with my mind comprehensively blown by what I’d seen. What I experienced was the exact programme any prospective FZED buyer will receive as part of the $650,000 purchase price, around £500,000 as I type; or, put another way, not a lot more than one of the pricier GT3 cars you might buy. You can race it in the BOSS GP Series, or just be the fastest person at any track day, anywhere in the world. And run it you can, because it doesn’t require an army of boffins to fire it up, and the Cosworth motor will go over 3000 miles on pump fuel between rebuilds, which is a hell of a lot of track time.

But what is most extraordinary is that the FZED represents the beginning, not the end of David Dicker’s ambitions. The FZERO promises another level of performance altogether – beyond that of modern F1 cars I’m told – and there’ll be a road-going version too, and another electric supercar as well.

You may never have heard of Rodin Cars before reading this, but having been to New Zealand, seen the track, the factory, the facilities, met the team and driven the car, I’m confident you’ll be hearing a whole lot more from it in future.