F1 Race Report

All the important prizes had already been taken by Abu Dhabi, a race that could’ve been a microcosm of the season as Lewis Hamilton drove to his 88th career victory,…

Few things in motor sport are more evocative than watching a solitary car lapping an otherwise empty circuit. Senses trained on a distant, fast-moving shape pursued by the howl of a highly tuned racing engine, the purity of the scene only serves to intensify the experience.

Private tests such as this are something I’ve witnessed probably a hundred times, but none has been quite like today. For starters it’s in Majorca (for reasons I will explain shortly) and, in place of an internal combustion engine working through its raucous ascending and descending scales, there’s a constant, piercing whine. Like a flightless helicopter without the thrashing rotor blades, this otherworldly noise is the shrill soundtrack to Audi’s new-generation Formula E racer. And we’re here to drive it.

Why Majorca? Because the compact, sinuous circuit is very close in character to the tight, twisty street circuits that are part of FE’s USP. It is a slightly odd place; a bit rough around the edges and with a somewhat improvised feel to it, it’s like a scaled-up kart track. This makes it ideal for a FE car and a great place to get a feel for both the old- and new-generation machines in a relatively safe yet representative environment.

We covered the difference between this and the car it replaces in the December 2018 edition of Motor Sport, but in case you missed it I’ll recap the most salient points. The altered look is very obvious, the new car somewhat self-consciously channelling a sci-fi future where the original car remained rooted in the present. There’s a massive diffuser, but it’s a bit of a red herring as FE is resolutely not an aero formula. Drag has been reduced thanks to enclosed wheels, but the original car’s aero wheel rims have been banned.

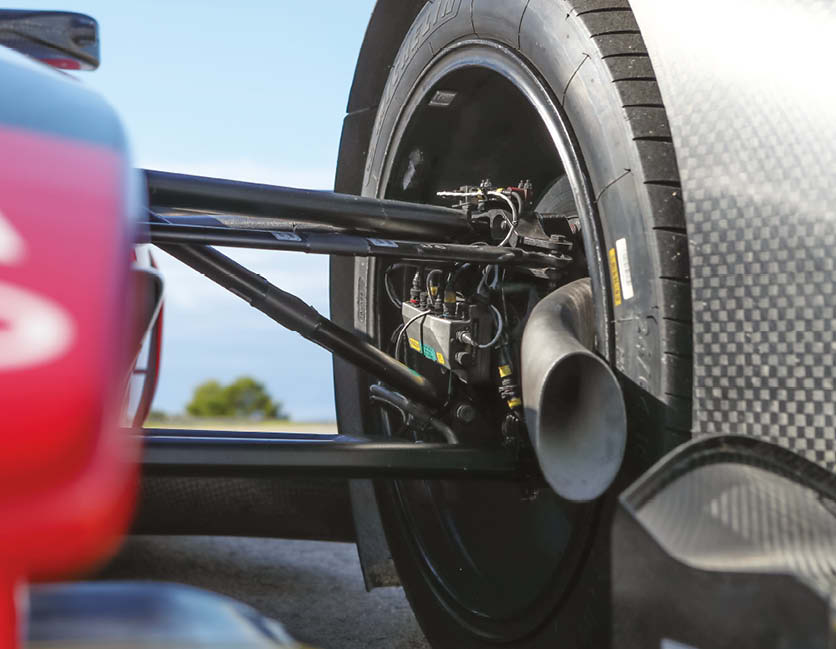

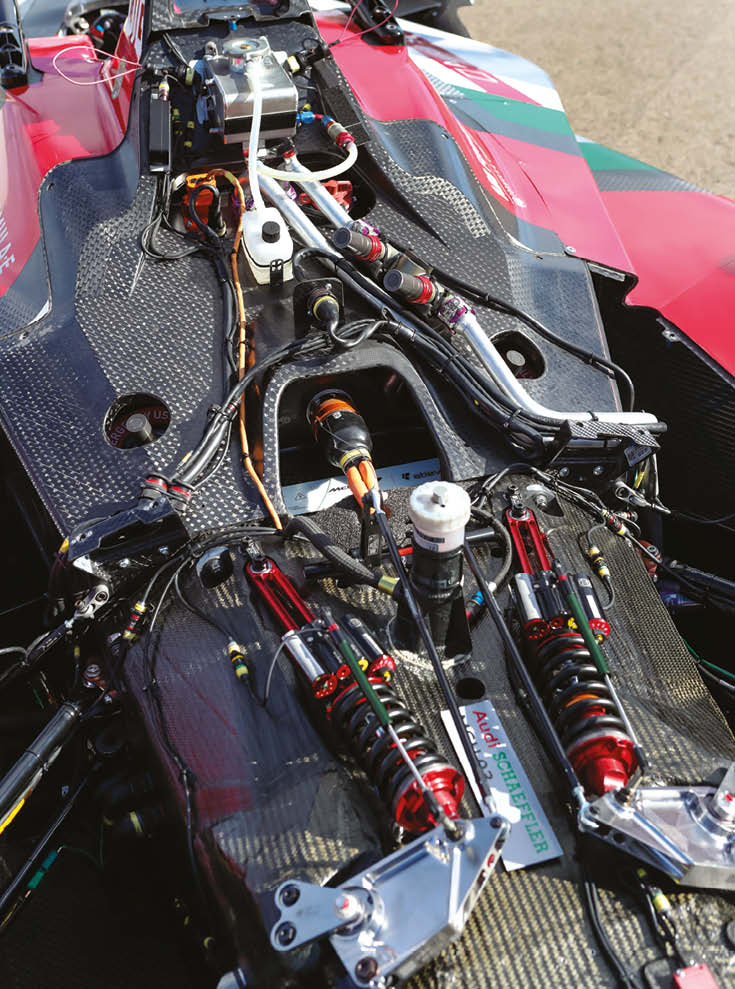

The tub is a spec design by Dallara and built by Spark Technologies. Teams were already allowed to develop their own powertrains – a big incentive for the major automotive players to get involved – but they are now also free to develop aspects of the rear suspension, including the dampers and packaging. Active brake-by-wire systems are now allowed (on the front axle only), with teams free to develop their own or use an off-the-shelf system.

Power management software has always been the freest area of FE’s otherwise tightly controlled technical regulations, so while testing is limited to just seven days per season and many areas of the car are standard or subject to development restrictions, the brain of the powertrain inverter can be developed during the season.

Biggest news is the latest battery pack. Produced by McLaren Applied Technologies, it has 54kW/h of useable energy; almost double that of the previous car. This means each 45-minute ePrix can now be completed without the need to swap cars – a big step in terms of credibility and a significant strategic shake-up.

Power is up compared to the Gen-1 cars, with 200kW (approx 268bhp in old money) available in race mode and 250kW (335bhp) in qualifying. That 50kW (67bhp) bump is also available through the familiar ‘FanBoost’ in-race vote process, and a new ‘Attack Mode‘ – the specifics of which (that’s to say the number and duration of shots) will be announced to the teams only an hour before each ePrix to add an element of unpredictability. Spectators and viewers know when Attack Mode has been engaged thanks to a special lighting system on the halo.

To help demonstrate how the fresh technology and power increase translate on the track, Audi has brought Lucas di Grassi’s Gen-1 car fresh from Season 4 along with the team’s first Gen-2 car, which was being used for official FE testing ahead of the first race in Saudi Arabia last December. It’s a rare privilege to drive a car so early in its racing life, and no small risk for Audi if the car was damaged during a handful of media tests.

“The Gen-1 car is a real handful in the braking areas, it rarely seems to behave the same way twice”

We start by driving the Gen-1 car. I’ve watched enough FE to know the outgoing car would be tricky, but if I’m honest I didn’t think it would be quite such a challenge. This has nothing to do with its pace, for it really doesn’t feel that fast. All things are relative, however, and it’s worth noting we are doing none of the energy management or almost continual brake bias adjustments the FE regulars have to cope with while racing.

This Gen-1 car is a real handful in the braking areas, for it rarely seems to behave in the same way twice. This is evident from the racing, but such is the shift in brake balance, not just lap to lap but sometimes from corner to corner, that you’re constantly reacting, correcting and modulating your braking efforts.

I’ve grown used to there being few if any transferable skills from historic racing to the modern realm, so the irony of feeling very much at home in a Formula E car is not lost on me. Especially when the rear wheels decide to lock under braking going into the chicane at the end of the longest straight. It’s quite a moment – one almost immediately followed by a similar lock-up into the chicane directly adjacent to where the Audi Sport guys are constantly monitoring my progress.

When I come in for my mid-stint pause, the chief technician has some fairly stern words of caution for me – and a look to match. Audi test driver Benoît Tréluyer is less scary and even offers a wry smile when attempting to calm me down, but the message is clear; please don’t push any harder. To be honest I’d already had that word with myself, but it was fun to push hard and to feel genuinely how tricky the limit is to find.

After my mild dressing-down in the old car, I approach the new one with a little more circumspection, for crunching it really wouldn’t go down well. It’s a very different car to behold, and a very different car to board thanks to the halo. Instead of stepping into the car I’m ushered towards what horsey people would refer to as a mounting block, from which I can step directly onto a specific area of the cockpit surround that’s solid enough to bear the weight of someone standing on it. From here you hoist one leg then the other over the halo’s sturdy metal hoop and stand on the seat before lowering your way in, remembering to keep your legs out straight so they thread down into the pedal box.

Initially you go a bit boss-eyed focusing on the halo’s central support spar, but once on the move it’s a relief to find you genuinely look through it. Initial impressions are of an immediately tighter, more responsive car. It feels bigger and visibility is severely impeded by the enclosed front wheels, to the point where I find it hard to place the car close to apex cones with the same confidence, even though I know the circuit by this point.

As with the original car there are no gears to shift, so it’s a case of pointing and squirting. The new motor and battery cells deliver more shove and a sharper, fizzier whine, but there’s the same sense of immense torque from rest followed by a linear, uninterrupted rate of propulsion. Like the Gen-1 car it reaches a plateau sooner than you expect, so while it’s still accelerating happily into the braking area along the FE test circuit’s longest straight, the impression of speed is moderate, as you’d expect in a 900kg car propelled by 268-335bhp.

Despite appearances there’s little to no downforce generated by the Buck Rogers bodywork, so you know you’ve only got mechanical grip. Ordinarily this is well inside my comfort zone, but there’s not a great deal of feel from the new iteration of Michelin’s treaded, all-weather rubber. They might be softer, but they have to go a race distance (unlike the old ones, which only ever did half a race) and you never get the reassuring sense they’ve switched on in the manner of a nice, grippy slick. In hands new to the peculiarities of a FE car, the effect is a little spooky.

This remoteness most readily manifests itself under braking, where it’s still easy to lock a wheel when slowing into a tight hairpin, at least early in a run when the tyres are still cold. According to feedback team principal Allan McNish has received from his drivers, the brake-by-wire system reduces the single trickiest car control-related aspect of driving a FE car, but it can still be a devilish job to get even temperatures into front and rear tyres, or even across each axle. It’s encouraging that these new cars require a driver not only to have feel, but a readiness to react and improvise.

I’ve already made a pact with myself not to drive as hard as I did in the old car. Still, it’s interesting to note that according to the steering wheel data screen, my best lap is nearly 0.4sec faster than my quickest in the old car. While far from an absolute benchmark, it’s an illustration of the new car’s greater pace and increased drivability. Though not as committed on the brakes, I’m enjoying the new car’s willingness to wag its tail under power; something the drivers won’t be doing for the fun of it, but will most likely have to embrace at the end of the race when the Michelins are potentially wrung out.

“It’s still easy to lock a wheel when slowing into a tight hairpin”

Driving both Formula E generations was as much a test of my own feelings on the future of motor sport as it is a simple evaluation of a new racing car. This explains why at the end of the day I was fascinated and better informed about FE, but still conflicted by what it offers. Both as a spectacle for fans and as a formula for the big manufacturers.

Unquestionably FE retains a laudable commitment to shaking things up. An opportunity to avoid well-worn motor sport tropes is one of the few luxuries FE’s founders enjoyed and, as electric propulsion becomes a greater part of the wider automotive industry strategy, its position as a marketing platform becomes exponentially stronger. These are two things F1 can’t claim.

Having tried both cars I know first-hand that they are challenging, though the new car feels far more polished than the one it replaces. This tells me that as the series matures and the cars evolve, FE will inevitably face the same problems as F1; namely the big brands’ desire to dominate, the engineers’ impulse to improve things and the racers’ instinct to go faster. As we’ve seen in F1, this cycle doesn’t guarantee better racing and often masks the drivers’ skill.

Another aspect I believe will become increasingly hard to reconcile is FE’s desire to peg the pace of development – and avoid an arms race. Not least because that’s precisely what the big automotive players (incumbent and emerging) are engaged in with road cars. Battery technology is something even the largest automotive brands prefer to develop in partnership with pure tech companies, so it makes sense for FE to keep teams focused on how to wring the most from what they have, rather than chase better battery tech.

Yet can we really expect some of the most illustrious, proud and fiercely competitive brands in the history of motor racing to remain committed to playing nicely, in order to nurture Formula E’s greater wellbeing? They might be happy to offer platitudes for now, but after going toe-to-toe in the World Endurance Championship’s hybrid era or battling (and beating) Ferrari in F1, how long will the likes of Audi, BMW, Mercedes (HWA) and Porsche suppress the feeling that they are going racing with one arm tied behind their backs?

Confining the cars to inner-city street circuits enforces a certain Darwinian evolutionary fitness for purpose, but it’s also a tacit acknowledgement that FE cars simply don’t cut it on full-scale tracks. Newcomers to motor sport see this as a plus, but although I understand the inner-city concept I’d be lying if I said I didn’t think it pales compared with the majestic scale and dazzling speed of internal combustion racing at traditional venues.

I’ve not been a fan of FE, though I’ve always been impressed by the best drivers’ abilities to go wheel-to-wheel within the wholly unforgiving confines of concrete-lined streets. It’s certainly refreshing to see racing in an environment where track limits are physical rather than philosophical. Having now experienced the original car, I’ve got even greater respect for the tricky and surprisingly old-school challenges they presented by having manually to manage their mechanical and regenerative braking systems.

It’s too early to say what effect the new Season 5 machines will have on the excitement of FE, but with a greater level of predictability under braking and without the need for a mid-race car swap, the unique variables thrown up by the Gen-1 car’s limitations have gone. Attack Mode will introduce dynamic, potentially race-changing opportunities, while fresh tactics to get the best from the available battery energy and tyre life will emerge as sim-honed strategies are fused with real-time race data.

Those drawn to motor sport by FE’s urbanite, family-friendly approach and futuristic technology will still find plenty to like about the latest cars and E Prix events. The fact there’s no longer the need to swap cars should boost battery racing’s credibility among traditional race fans, a demographic that has struggled to engage with FE emotionally. I’d count myself among that group.

Being brutally honest, driving Audi’s old and new FE cars hasn’t brought me any closer to loving them – they remain essentially cold-hearted appliances – but it has taught me this much: that racing is racing and racers are racers, whatever the means of propulsion. I’ll be tuning in to the rest of Season 5 with interest.

The new Formula E car doesn’t just look different to it’s predecessor it’s more advanced under the skin too as this comparison of Jaguar’s two cars shows.

Battery capacity: 28kWh

Battery weight: 310kg

Number of cells: 165

Max. power (qualification): 220kW (295bhp)

Max. power (race): 180kW (240bhp)

Charging time: n/a

Min. weight (with driver): 880kg

Length: 5000mm

Width: 1780mm

Height: 1050mm

Max. speed: 225kph (140mph)

Acceleration (0-100kph): 3.0sec

Battery capacity: 52kWh

Battery weight: 385kg

Number of cells: 209

Max. power (qualification): 250kW (335bhp)

Max. power (race): 200kW (268bhp)

Charging time: 45mins approx.

Min. weight (with driver): 900kg

Length: 5160mm

Width: 1770mm

Height: 1050mm

Max. speed: 280kph (174mph)

Acceleration (0-100kph): 2.8sec