Artist, genius, free spirit

Thackwell’s co-instructor and his favourite team manager recall a man of parts James Weaver came through Formula Ford with Mike Thackwell, and in 1978 both men were instructors at Mike…

Lyndon McNeil

Like many great motoring tales, this one began with a Mk1 Volkswagen Golf. Unlike many great motoring tales, that small German hatchback inadvertently spawned the rebirth of GT racing and sparked Stéphane Ratel’s global empire.

Currently running 12 championships, the modestly named Stéphane Ratel Organisation has grown to be a powerhouse of modern racing. Its flagship Blancpain GT Series is the world’s leading category of its kind and SRO counts major events such as the Spa 24 Hours, Bathurst 12 Hours and FIA GT World Cup among its portfolio. This year alone, it will host 100 championship rounds across 53 events on five continents. No other independent race organiser can match those figures. It’s fair to say that it’s been a busy quarter-century for Ratel and the SRO.

To learn more we arrange to meet at The Ivy Chelsea Garden on King’s Road, close to SRO’s office in London. It’s a city Ratel knows well from the 1980s, when he plied his trade through car dealing and high-end fashion retail – as his Dolce & Gabbana suit, Thomas Pink shirt and Hermès tie testify. Yet there’s nothing flash or arrogant about him. Ratel is incredibly aware of his own roots, regardless of his current position. “You know,” he says, “the first race meeting I ever attended was the first one I organised!” Sounds a bizarre fact, but it’s true.

Born in Perpignan, France, in July 1963, Ratel’s family had no motor sport background – nor even a particular interest in cars. Instead, he found his way into race organisation mostly by chance.

“Everybody thinks that I was a racer first and then turned into a promoter,” he says. “But it’s almost completely the other way around as I was a promoter first without ever really being aware of it.

“It’s weird because I got into cars and motor sport via business, first and foremost. I didn’t grow up with flash cars and my family had zero interest in them. I don’t think I ever heard my parents talk about cars. I never watched a race until I organised one, not even on TV. But life has a funny way of doing things. I just believe in taking the chances life gives you, and that’s what’s led me here. I’ve been running around pretty much non-stop for 25 years.”

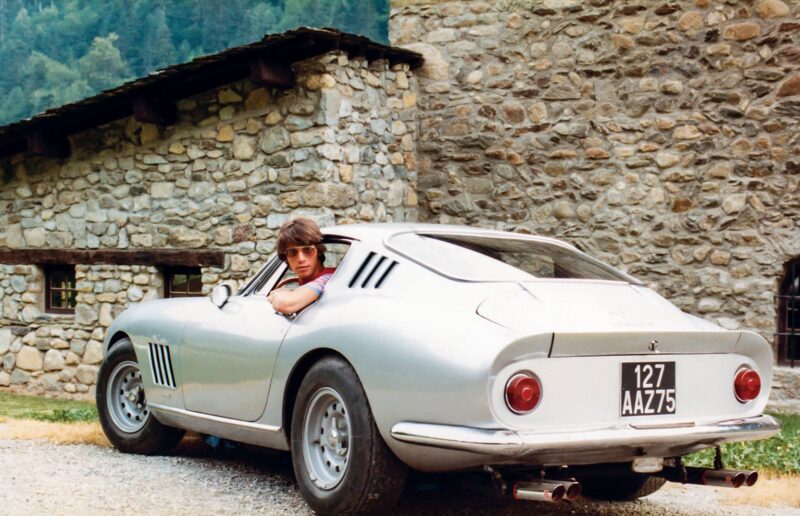

Ratel’s first car was a VW Golf. He graduated to a Ferrari 275, bought from the father of a girlfriend

‘Here’ is arguably one of the most influential positions in the modern sport. Across the first 25 years of SRO, Ratel has found himself going from running legally questionable street races to forging alliances with Bernie Ecclestone and, eventually, becoming the figurehead for GT racing. He created GT3, GT4 and also defied the naysayers to begin a world championship for manufacturers in the face of near-overwhelming financial odds.

But where does that Golf come into it?

Ratel grew up in Paris in the care of his godfather, following the death of both parents and his sister when he was still a teenager. His family has a long military history. His father was an officer in the French Army while his godfather is a descendant of Maréchal Joffre (Marshal Joseph Joffre, who was instrumental in saving France by stopping the German advance to Paris in WW1, winning The Battle of the Marne in 1914).

Ratel did come from money – as he puts it, “Most kids had pocket money and parents, I had an inheritance” – but what he’s gone on to create more than justifies his early expenditure.

Upon gaining his French Baccalaureate, Ratel’s godfather bought him his first car – that Golf.

“I’d had a hard time in many ways growing up – but I just remember thinking at that point ‘Wow, I’m going to get a car!’ It wasn’t something I spent much time considering, but the car of the moment back then was the Golf GTi,” says Ratel. “So I got a Golf, but there was then the problem of insuring it in central Paris as an 18-year-old. It was almost impossible. The insurance was taking up a third of what I had to live on, but we found a loophole where you could insure a classic or historic car on specialist insurance for much less. The Golf had ignited my passion for cars, so I sold it and bought a VW Beetle – and a Jaguar E-type, which was strangely affordable back then!”

It was the 4.2-litre E-type that gave Ratel his first real taste of speed.

“My friend and I took it to Germany on the autobahn for a trip and I remember this Porsche 911 coming flying past us and my friend screaming at me ‘Go after it, go after it!’ So, of course, I go,” he says. “We watched the speedo – 180-200-220kph and then… booom! The engine went blang, blang, blang with oil everywhere… but I had to learn while I was young. We sat on the hard shoulder with the engine in pieces and my friend was just shouting ‘Crap old British cars – if you had a Porsche we’d be fine.’ From that moment I wanted a Porsche, but I couldn’t bring myself to ask my godfather for one as he was controlling my inheritance. Then the bank called to say my mother had some savings I had to collect… and inside this little safe was just enough cash for a 911. So I went and bought one, which was not a very reasonable thing to do, but my passion had really set in by then and there was no stopping me. But when I got the car my godfather wouldn’t give me permission to park it outside the house!”

That Porsche came from a young French doctor named Jacques Tropenat, who had an image on the wall of the very car Ratel was buying. It was on a circuit. Tropenat – now the medical delegate for both the World Touring Car Cup and World Endurance Championship – introduced Ratel to track days via the Porsche Club of France.

That could have provided an ideal entry point to the sport, but Ratel’s attention was instead swayed by a silver Ferrari 275 GTB/4 owned by the father of a girlfriend. After wrangling with his godfather to allow him to “blow all my inheritance in probably the dumbest way possible – but I managed to convince him it would be a good investment” Ratel owned the car, but swapped it soon after for a more modern 512 BB.

“Then something nobody expected happened, the value of classic cars started to skyrocket – I sold the 512 BB for more money than I paid for it. Even though the value of my old 275 had basically doubled in comparison, it didn’t stop me telling my godfather, ‘See, I told you so!’ That was my glory day…”

After completing his national service where he did duty as an intelligence officer for the French Air Force – something he still credits with making him a good public speaker – Ratel moved to California to study at university, where his first real business opportunity awaited.

Ratel’s breakthrough came with the 1992 Venturi Trophy

“I got off the plane, went straight to a car dealership and there was a 512 in the window – exactly the same as the car I just sold in Europe, but it was half the price. So, my first day in America, and not speaking English very well, and I find this car at a bargain price and see an opportunity.”

With the US dollar strong against the European currencies, many Americans bought European-spec cars and shipped them out to the US. But when the currencies shifted the opposite way, the value of these ‘grey market’ cars plummeted. For Ratel, with European connections and cash to spend, it was unmissable. He began buying multiple cars and shipping them to Europe to resell at a profit.

“I remember buying the first car and taking it back home with me at Christmas on a plane. I sold it almost as soon as it arrived. I started buying and selling more and more cars, and made good money from it.”

Ratel sold many cars at auction, avoiding VAT and import duties under EEC law at the time, and gradually developed a successful business. He even treated himself to his dream car – a white Lamborghini Countach, purchased from the Drug Enforcement Agency.

“There was a time when I lived in California, drove a white Lamborghini with white interior and wore a white suit, had long hair and a big gold Rolex… I looked like something out of Miami Vice,” he says with a chuckle. “My conservative godfather took one look at me and… let’s not say he insisted I go back to France, but it was strongly suggested.”

With America off-limits, Ratel set up fashion shops in London’s Sloane Street and St Tropez and counted celebrities such as Sir Elton John among his clientèle. But he lost almost everything in the financial crash of 1991. His car dealings collapsed, as did demand for his high-ticket fashion stock.

The decision to allow Porsche’s controversial 911 GT1 sparked an arms race in the BPR Series

Motorsport Images

It was while Ratel was at his lowest ebb that motor sport first appeared on the horizon for him.

“I moved back to Paris and had a housewarming party with many friends and clients, and we decided to have a race,” he says. “We knew about the Cannonball Run, so we all decided to drive from Paris to St Tropez, with the first one there getting a trophy. Soon a few magazines picked up on what we were doing and we got some cool coverage, and I guess that was the first event I ever organised – but looking back it was a hugely stupid thing to try and do!

“Regardless, we all enjoyed it and said we’d do it again. Then a law student friend of mine said to me, ‘Don’t dare do that again because if somebody has an accident, you’d be for it. If you must do it, rent a track.’ So we did. One of my friends had a Venturi cars contact, who came to me and said: ‘If you race a Countach or a Testarossa, you’ll do two laps before you break it – so let us make you some cars instead.”

Venturi and Ratel came to an agreement to produce 24 cars, each with lightweight chassis and 400bhp twin-turbocharged engines. In that deal the Venturi 400 Trophy was born for 1992. Ratel managed to sell 30 cars in a single day, spreading the word about this Ferrari F40 lookalike to his contacts. As word of his ‘gentlemen drivers trophy’ concept spread, no fewer than 55 cars were shipped for year one, and a date at Le Mans was booked. Just a week after the world famous 24 Hours suffered its worst-ever entry – only 28 starters and just 14 finishers – Ratel took his 55 Venturi Trophy cars to the track, prompting a chat with Alain Bertaut, vice president of Le Mans organiser, the Automobile Club de l’Ouest.

“It all happened so fast,” says Ratel. “We’d gone from a hotel lobby, where I’d convinced my friends that the Venturi was much more than a little plastic car with a Renault engine, to having clients like Riccardo Agusta [of the MV Agusta motorcycle empire] sign up. Riccardo was desperate to do Le Mans so we went there. I’ve barely been to a race event in my life and suddenly I’m talking about getting Venturi onto the grid for the 1993 Le Mans 24 Hours!

“We worked out a GT regulation for the 400, and I went back to Venturi and pitched the modifications to them. However, at the time the company was also involved in Formula 1 with Larrousse and that was a financial disaster. Suddenly Venturi wanted to stop everything. A Le Mans upgrade was now out of the question, and I ended up pleading with them to save the 400 Trophy as that would have been the end of me as a businessman because all of my friends had bought cars and invested in it. We kept the Trophy going, but I wasn’t prepared to let the Le Mans idea die.”

Ratel put together a handful of deals, including trading some of his remaining car collection, to finance the build of the Venturi 500LM cars. The plan needed four to be complete in order to recoup the investment back. He sold eight.

“I’ll never forget Le Mans that year,” he adds. “I don’t think I slept for a week. We turned up with seven cars for the 24 Hours and I’d entered one through my own team, plus more than 60 Trophy cars for a support race, and I had to manage the lot! It was just me and an assistant for the week and it was the most stressful time. Madness. To add to the pressure, we also had a driver called Christophe Dechavanne, who was the number one TV celebrity in France at the time [a talk show host who was France’s answer to Jerry Springer]. We were on the cover of every magazine with him and the media attention was huge. Plus there were many in the paddock going ‘Look at this young fool coming to Le Mans with seven cars, we won’t see one after two hours.’ We ended up getting five to the finish.”

That was truly the start of Ratel’s organisational career. He took what had been learned with Venturi and expanded dramatically when he spotted a niche in the market. Following the demise of the World Sports Car Championship in 1992, global motor sport was bereft of a sports car series and there had been practically no professional-level GT racing since production-based cars were killed off by the shift to prototypes.

“After Le Mans we had a problem that we had these eight 500LMs and nothing else to do with them,” he says. “I had some friends with Ferraris, and then got a call from Patrick Peter, who had just revived the Tour Auto. Plus Jürgen Barth was running Porsche racing over in Germany, so we decided to get together and run a series.”

BPR – Barth, Peter, Ratel – was an instant hit when it launched in 1994, attracting 30-car grids before the end of the year with Venturi and Porsche entries gradually joined by models like the Ferrari F40, Lotus Esprit and Callaway Corvette.

“There was nothing like it at the time. The World Sports Car Championship was finished and GT racing had essentially been dead since the mid-1980s, so there was this vacuum where nobody had done racing like this for a long time. BPR came along at the right time. But we had to rebuild everything and start from scratch.”

The success of the BPR Series – launched with Patrick Peter and Jürgen Barth – laid the foundations for almost all of the modern GT categories

Ratel founded SRO in 1995 to look after his stake in BPR and also organise the new Lamborghini Supertrophy, which he had started as a sideline. But with success also came the politics that go with motor sport at a high level and the BPR Series soon faced what Ratel describes as “a double threat”.

Firstly, the McLaren F1 GTR was sweeping the board. Never specifically intended for racing, the ultimate road car of the 1990s translated into the ultimate GT racer, too, sparking an arms race.

Fed up of being trounced, Porsche responded by developing its mid-engined 911 GT1 prototype, getting around the homologation rule by producing 25 road-going examples of what was a pure-bred racing car. When Porsche applied to join BPR and take on McLaren, Peter was against it, Barth was tied by his conflict of interest and so the casting vote came down to Ratel.

“The Porsche decision was a big moment. I ultimately said ‘OK, we take the car and move on’ but it created a huge commotion and the McLaren owners were furious. In hindsight it probably was the wrong decision, but it paved the way for some amazing cars like the McLaren F1 Longtail and Mercedes CLK GTR to join and try to beat Porsche.”

But the more dangerous threat came from the top of the tree and brought about a tense encounter with the FIA and F1 chief Bernie Ecclestone (see panel overleaf).

Following the end of BPR and his exploits with the resulting FIA GT Championship – now renamed and reformatted into the Blancpain GT Series – Ratel’s work wasn’t done. In partnership with the ACO he helped launch the Le Mans Endurance Series and took over and rejuvenated the British GT and Formula Three championships as well as the French GT series and others.

But something was still missing – a truly global GT competition. Cue the 2010 FIA GT1 World Championship – Ratel’s biggest gamble, success, and perhaps also failure.

“The concept for World GT1 was great – we wanted 24 cars, shared between six manufacturers with two teams running two cars each. It was very ambitious, and it did work. We had Aston Martin, Lamborghini, Corvette, Nissan, Ford and Maserati – we had the numbers and an even share of manufacturers, but it wasn’t financially sustainable from day one. The sheer logistical cost of racing around the world was huge, and we launched it at the time of a global financial crisis, so getting it up and running at all was an amazing achievement. Everybody said it had a 90 per cent chance of failure and laughed when we first announced the plan. But it was like F1 for GT cars and it was beautiful, but after a few years it was a complete financial failure.

“I’ve made mistakes in my career, but my biggest was not giving up on GT1 when the FIA and ACO launched the World Endurance Championship for 2012. I guess there was too much vanity from me and, looking back, I can see there couldn’t be two world championships. I lost so much money and it hurt SRO badly, that’s when we withdrew and focused purely on GT3 and GT4.”

Ratel’s philosophy of always keeping more than one plate spinning paid off most when he noticed a seed of opportunity within his Lamborghini Supertrophy. While running the powerful production-based Diablos as a support to FIA GT, he noticed that they could lap almost as fast as full GT2-spec cars, but at a fraction of the price.

“When Lamborghini stopped the Supertrophy in 2002, I took the rules concept to as many manufacturers that would listen, and the beauty of it was that GT3 was simple and affordable. Instead of having to build 25 cars to homologate a certain model for racing, manufacturers could build four or five and it just took off.”

Within the Supertrophy, SRO honed the technical rules, the driver grading system and its Pro-Am format, which has proven so popular in its domestic categories, and translated it into the multi-marque global phenomenon that GT3 has become. If you’re fortunate enough to own a GT3 car, you could technically race it anywhere in the world on almost any given weekend, such has been the widespread acceptance of the format.

FIA GT1 World Championship was stunning, but short lived and a financial failure for SRO

Motorsport Images

Not all Ratel’s ideas have been universally popular, and balance of performance (or BoP) remains a hot topic among the purists. A concept of Max Mosley and administered by Ratel, its 2004 introduction was a direct response to Maserati’s MC12, which threatened to reignite the costly homologation special war all over again.

“Things had just settled in FIA GT after the Porsche and McLaren storms of the late 1990s, and then suddenly Maserati brings this new car, which is basically another GT1 prototype. With Ferrari’s involvement in its development, politically we couldn’t say no to it, but instead we added weight to balance things out.

“The concept of balancing was the very antithesis of racing and we had nobody willing to accept what we were trying to do. But we proved in 2005 that it worked, when we had the FIA GT title decided by one point in favour of a Ferrari 550 over the Maserati. BoP is a necessity in GT3, when you have so many different brands and type of car racing. It’s a mix of grand touring cars and supercars and the manufacturers want them to race together, and BoP is the only way to do that.”

With so many different projects on the go, spread all around the world, Ratel has needed to remain committed. “It’s an intense life, and an intense business,” he says. “I do about 35 weekends per year and it’s not the type of job where you can wake up on Monday and decide to take a day off. This is a life where you’re constantly on the move. I’ve missed everything – birthdays, weddings, celebrations… everything! But I don’t call it work, I do what I love to do. From the first day I bought a car I’ve been living out my passion for automobiles, and my passion for chasing sales. I’ve even gone from selling cars and race entries to friends to selling global championships to manufacturers. But the pleasure I get from doing it is the same at any level.

“I’m not a championship promoter now, I’m a category promoter. And with SRO – now the walls are built and the roof is on, I can leave the internal design to my team and enjoy things more.”

Ratel keeps a keen and watchful eye over global GT racing

Motorsport Images

But what about his driving career?

“Rubbish, I was a lousy racer!” he laughs. “I raced a bit and did development on the Venturi Le Mans programme. I did Le Mans in 1994 with Agusta, and shone in the first Zhuhai street race as a late entry. Qualifying was my first practice and I started last, but then had the best race of my life, got up to fourth and thought ‘I’m on fire here!’ But then of course I crashed. The speed I showed got me a bit of a reputation and a few last-minute invites to race in other places. My best-ever result was second in GT2 class at the 1000km of Suzuka in 1995.

“I dipped in and out of driving but was always better at organising. I did buy a factory Bentley Continental GT3 and entered one of my GT Sports Club events at Barcelona last year, but I crashed it in practice. I was running between paddocks organising and wasn’t properly focused on driving so didn’t notice the traction control setting was wrong and went off. If I drive, then I need to only drive, not organise.”

Then comes a quick glance at the watch – a Blancpain Fifty Fathoms, what else? – followed by “Oh no! I was meant to meet David Brabham an hour ago! I told you I’ve always been running, and I’ve not stopped yet!”

His exit is swift, yet polite. I’ve no idea what type of car ferried him away, but I’d bet it wasn’t a Golf.

Born: 23/7/1963 in Perpignan, France

1992 Venturi Trophy founded

1993 Masterminds Venturi’s Le Mans programme

1994 Co-founds BPR with Patrick Peter & Jürgen Barth

1995 SRO founded, Lamborghini Supertrophy

1997 Co-founds FIA GT with Bernie Ecclestone

2004 SRO takes over promotion of British GT and Formula 3

2005 First GT3 race is held

2006 FIA GT becomes FIA GT3 Championship

2010 FIA GT1 World Championship launched

2012 FIA GT1 folds

2013 FIA GT3 is relabelled Blancpain Endurance Series

2016 Intercontinental GT Challenge introduced to combine Bathurst 12Hrs, Spa 24Hrs and Sepang 12Hrs

2017 Blancpain Asia Series launched

2018 SRO becomes majority shareholder in Pirelli World Challenge, USA